Sitting across a desk from one another on the fourth floor of the Physical Life Sciences Budling, University of Virginia biology professors Ali Güler and Iggy Provencio admitted their differences.

“Between the two of us,” Güler said, “we’re probably living like four or five hours apart. I wake up as early as 4 a.m. What time do you wake up?”

“Without an alarm,” Provencio responded, “maybe 10.”

“So, six hours apart,” Güler said. “It’s like we’re not even living in the same country.”

The early bird and the night owl had just spent a half-hour of their morning discussing daylight saving time versus standard time, whether the biannual clock-changing in the United States is still worth it and what the best possible alternatives are going forward.

Like Güler and Provencio, different people abide by different patterns. Some have their most energy in the morning, but are in bed before 9 p.m. Others might feel their most productive in the evening, but might need an extra cup of coffee to get going in the morning.

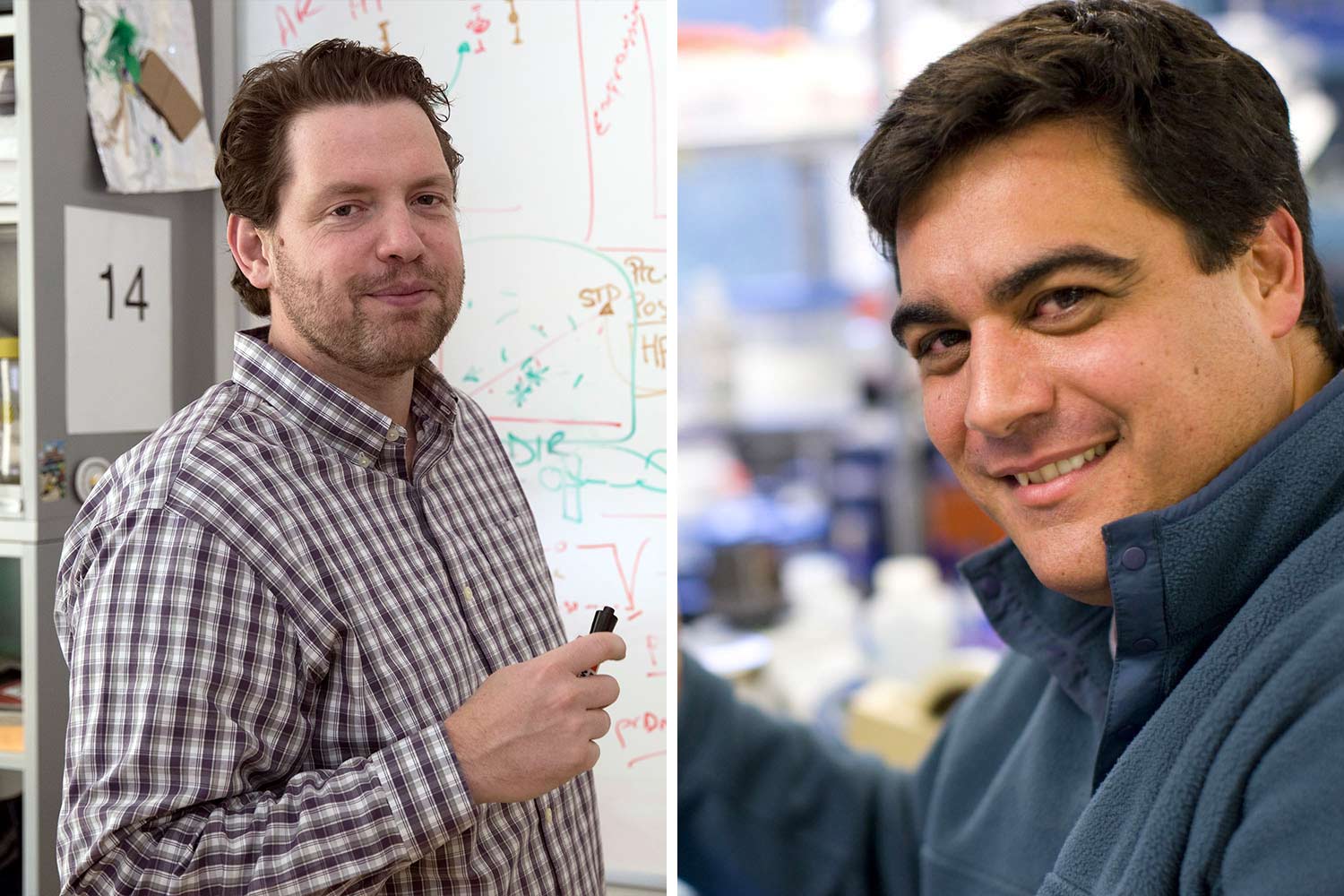

UVA biology professors Ali Güler (left) and Iggy Provencio agree that perennial standard time offers the most health benefits. (Contributed photos)

The former, then, might favor standard time, when the sun rise typically aligns with a wake-up call, while the latter might prefer daylight saving time and its later sunsets.

In this case, though, the latter, Provencio, has a Ph.D. from UVA in biology and teaches a course called “Biological Clocks.”

“Intellectually, I prefer standard time,” he said. “Emotionally, I prefer daylight saving time because I’m pretty much an owl and I would prefer to have more light in the evening. But intellectually, I can’t justify it.”

This Sunday, 48 states – Hawaii and most of Arizona are the lone exceptions – will “spring forward” their clocks an hour as part of daylight saving time. Clocks will then “fall back” an hour on the first Sunday in November. This cycle – except for a 10-month period in 1974, at the height of the Arab oil embargo – has been ongoing in the U.S. since 1966 and the establishment of the Uniform Time Act. The Energy Policy Act of 2005 added four weeks to daylight saving time by changing its start from April to March.

Today, the U.S. is among only 70 of the 195 countries globally to still observe daylight saving time. While there’s been political movement to the contrary – USA Today reported in November that 19 states, over the past four years, have enacted legislation or passed resolutions to provide year-round daylight saving time – scientists say year-round standard time provides the most health benefits.

“The clock in your brain is synchronized by external cues,” Güler said. “The most important being the sunrise and sunset. And you can interfere with it by other light. That’s why light at night is not a good thing, because it’s mimicking the sunrise. So that information will be taken by your brain and say, ‘OK, adjust your clock accordingly.’”

According to research conducted from 2009-16 at the Bronx’s Montefiore Medical Center, the risk of heart attacks and stroke increases by 24% when clocks go forward in the spring and an extra hour of sleep is lost. That risk then falls by 21% when clocks go back in the fall and that extra hour of sleep is regained.