“I don’t think we thought a lot about it … and then the diagnosis made it real,” Shannon Barker said on a recent Monday night in her family’s Craftsman-style home. “And then, I couldn’t compartmentalize it anymore and then we had to come to terms.”

The Barker family – mom and dad are both University of Virginia professors – had just finished making an apple crisp. Rescue dog Kady was circling the kitchen island for scraps.

It was a few weeks before Halloween and 13-year-old Leo was planning to dress as a banana because it would be funny. His 16-year-old sister, Finn, had a party to go to and was still deciding what to wear.

The diagnosis Shannon was talking about had been delivered three years earlier, when Leo was 10. She hadn’t been at the doctor’s office that day. Her husband, Tom, a professor of biomedical engineering in UVA’s School of Engineering and Applied Science, was there alone.

“The first words out of this guy’s mouth were, ‘You’re very lucky,” Tom recalled the doctor saying. “It’s like, ‘Oh, OK. I am?’ He says, ‘Yeah, because the Virginia School for the Blind is only 30 minutes away.’”

The disease that steals your eyesight

Leo Charles Barker is named for his grandfathers. Leo was the name of his mother’s father; Charles was Tom’s father. Grandfather Leo had an incurable condition called choroideremia, a rare, X-linked disease that slowly steals a person’s eyesight. Shannon inherited the gene, but not the disease, which mostly affects males, about 1 in 50,000. She – an associate professor of biomedical engineering at UVA – and Tom knew there was a 50-50 chance Leo carried the gene. He would need to be tested. They waited until he was 10.

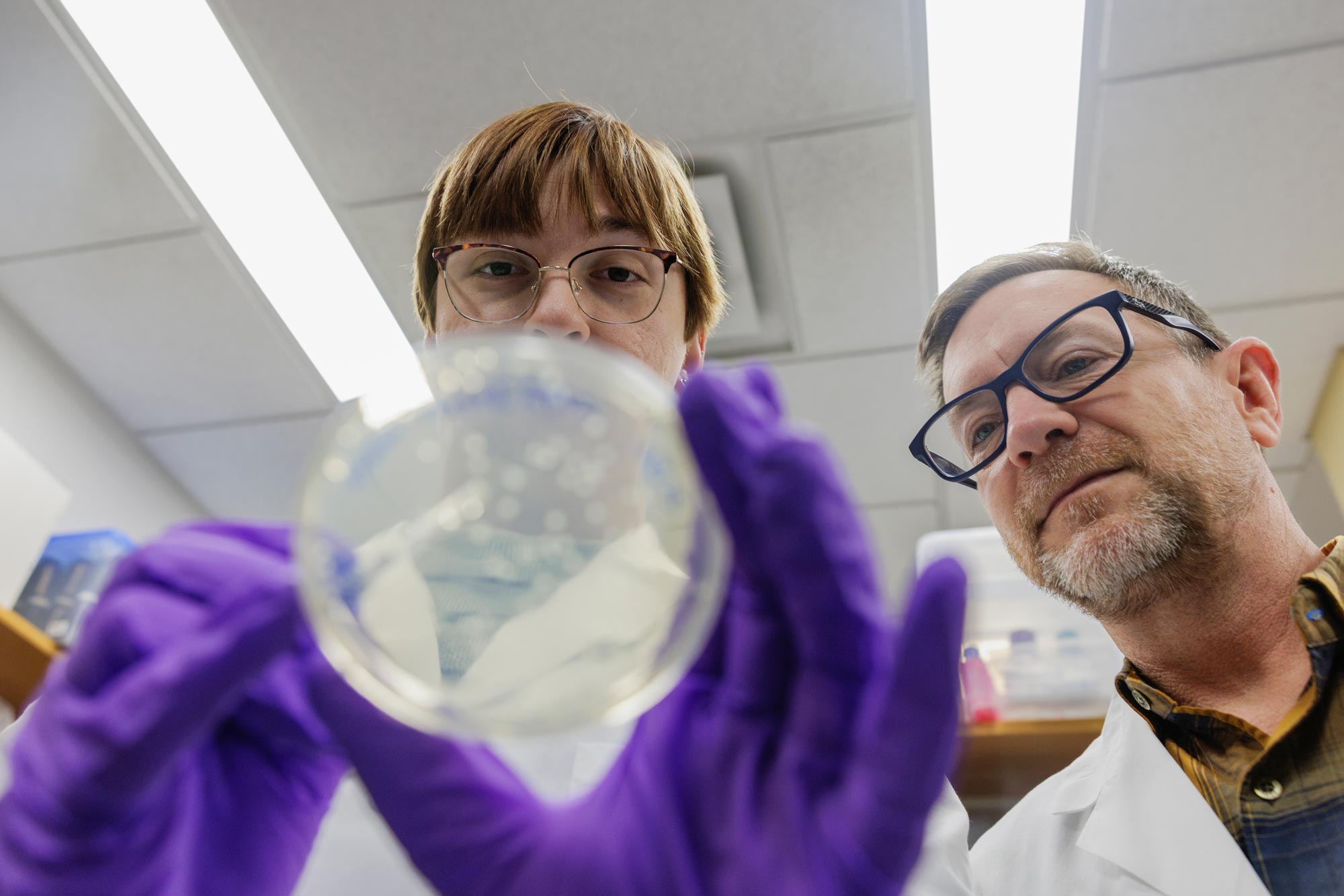

Graduate student Emily Baum, left, works with Barker in his lab. She joined his team knowing he hadn’t yet secured funding for his choroideremia research. “I was confident in Tom's ability to get funding for such a really important project,” she said. (Photo by Lathan Goumas, University Communications)

“I think we … honestly put off the testing longer than some parents do because we wanted those years of worry-free quote, unquote, time with him,” Tom said. They had the testing done after noticing Leo was beginning to have trouble with night vision, an early, telltale sign of the disease. After the diagnosis, they waited another year to deliver the news to their son.

“We wanted to make sure that he had enough confidence, enough understanding of what it means,” Shannon said, “so that he could understand that that doesn’t mean the end of the world. That there’s still … opportunities for a full life.”

‘I just need to buy my son a decade’

The first 25 years of his professional life, Tom focused on seeking a cure for lung fibrosis, a disease that, by heartbreaking happenstance, killed his father, Charles, nine months after he was diagnosed and three months after Leo’s diagnosis.

“I’d been working in this space for 25 years and you can imagine … it’s this thought of, ‘Did I do enough? Did I work hard enough?’” Tom said. “So, within the span of four months, it was just like the hits just kept coming. And so, it started me on this journey in late 2023.”

The journey is Tom’s complete reimagining of his lab at UVA. Together with his graduate and undergraduate students, he’s working furiously not to find a cure for choroideremia, but a way to pause its progression while other “really smart people” continue to seek a cure, hopefully within the next 10 years.

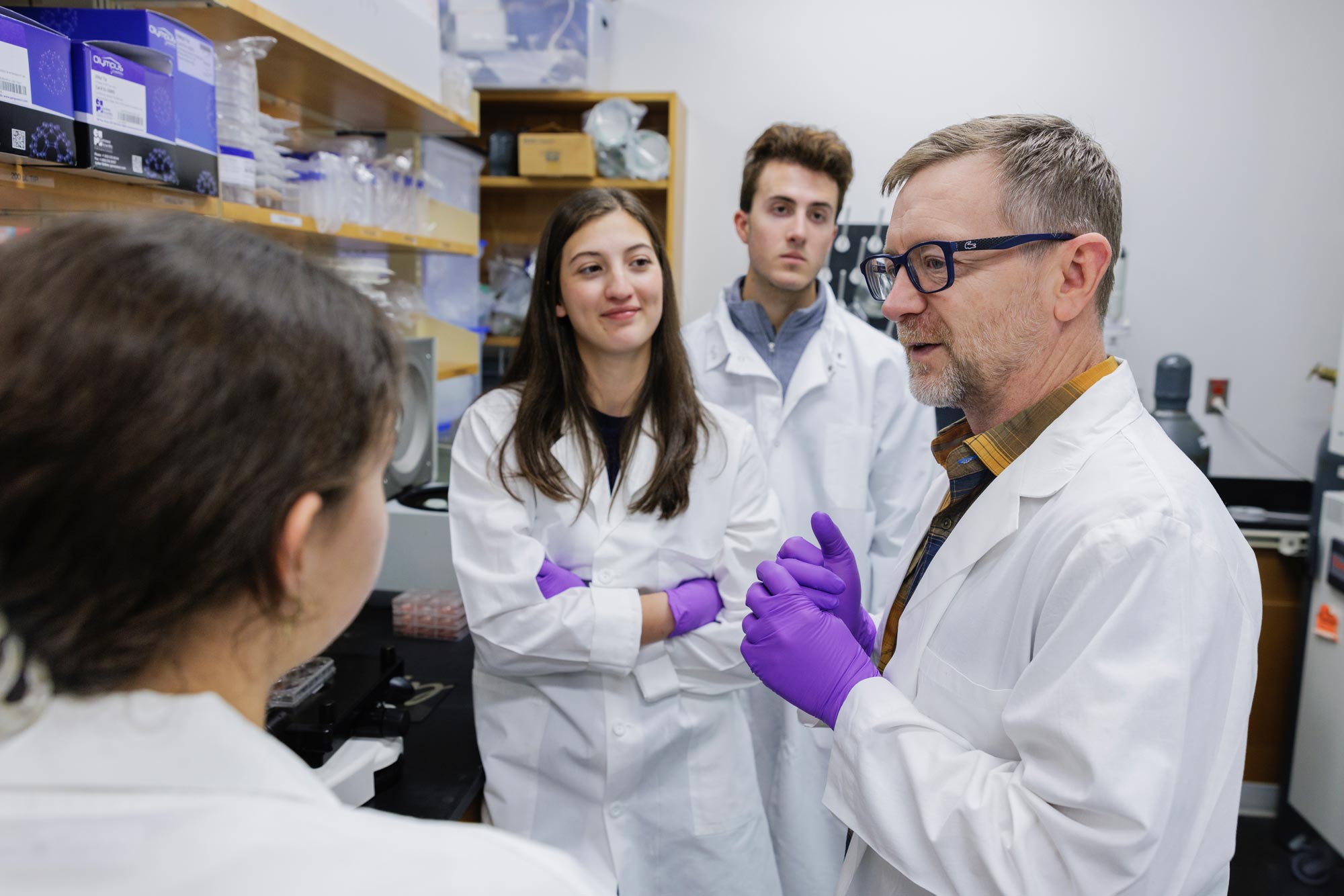

Fourth-year student Grace Burns, center, is running Sunday’s Marine Corps Marathon to help raise money for the Choroideremia Research Foundation. (Photo by Lathan Goumas, University Communications)

“I said, ‘You know what? I just need to buy my son a decade,’” Tom said. “Our approach really is, ‘Let’s not try to hit the home run. Let’s try to get a double.’ Let’s try to move the players around the bases by finding technologies or being clever about our approach that extends the lifespan of these (damaged) cells a bit longer.”

How is Leo?

Tom says the progression of choroideremia varies by person. “I think for a long time, it was believed that these patients followed a fairly similar timeline,” he said. “I’ve talked to some 35-year-olds that have very, very limited vision,” while there are others in the same age group that “operate fairly normally.”

Statistics suggest Leo will continue to lose his vision in his late teens and early 20s. Vision loss begins in the periphery and slowly moves inward to the center vision.