Dribbles&Data

It was Jan. 7 and Tony Bennett was on the verge of becoming the winningest men’s basketball coach in University of Virginia history. A good game from fifth-year guard Kihei Clark could help make it happen.

So Natalie Kupperman and Mike Curtis focused on Clark’s stats. Not his points and rebounds, but instead a trove of digital data that measured Clark’s core as a basketball player, in much the same way a NASCAR team might pore over an engine analysis.

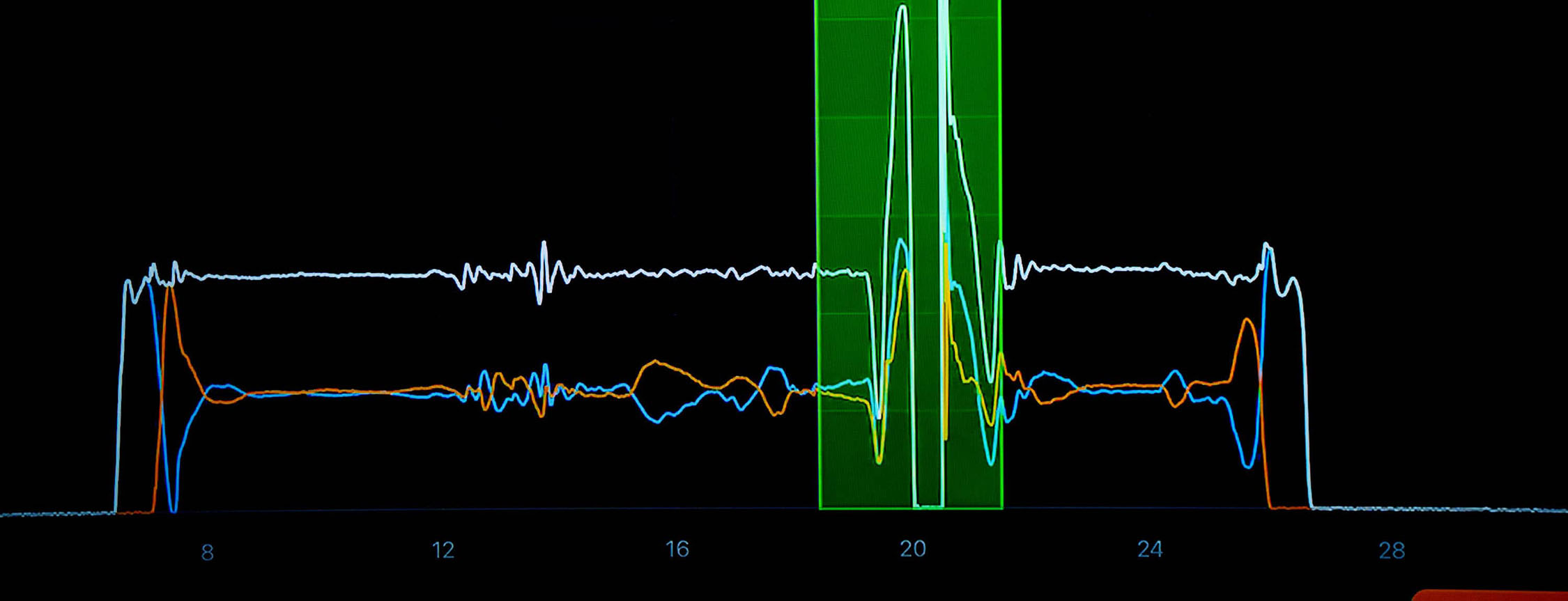

Clark slept 5 ½ hours the night before the game, including two hours of deep, restorative slumber. In the weight room 48 hours earlier, Clark put his hands on his hips and – on Curtis’ command – sprang from the floor. Pressure plates embedded in the floor zapped signals to a computer before Clark landed. On a video screen, animated lines shot up like the peaks on a heart monitor and then settled back to flat.

Clark’s hop was 21 inches, and that’s his normal mark. But the heaps of data Kupperman and Curtis analyzed showed the player from Woodland Hills, California, wasn’t his normal self. A stretch of hard practices, demanding games and taxing classes were taking a bit of a toll.

Kupperman and Curtis adjusted Clark’s workout plans to speed his recovery ahead of game day with Syracuse.

In that matchup, Clark dished a game-high 11 assists and Bennett got the historic win.

More than a decade ago, Mike Curtis, the men’s basketball team head strength and conditioning coach, began exploring how he could use data to improve practices and training. Natalie Kupperman, a sports scientist and assistant professor at UVA’s School of Data Science, later joined the effort with her expertise in wearable technology and data analysis.

These data dives into players like Clark are the cornerstone of a burgeoning UVA effort coupling the vast number-crunching abilities of UVA’s School of Data Science with a nationally ranked basketball program guided by coaches known for their cerebral approach.

“If we can make our athletes happier, healthier and just better functioning as humans, that’s huge,” said Kupperman, an assistant professor of data science who specializes in using data to improve athlete training.

For Curtis, the basketball team’s head strength and conditioning coach, his focus is on “availability” and what he calls “acute readiness,” or keeping the players healthy, rested and at top potential for competition. So weekly, daily and sometimes hourly, Kupperman and Curtis ingest a torrent of data from the 15 players.

Ben Vander Plas, a forward on the team, said UVA’s focus on the science of the sport “helps me recover in the best way possible” from the demands of academics, practices and playing. (Photo by Emily Faith Morgan, UVA Communications)

Ben Vander Plas, a graduate student who transferred to Virginia from Ohio University, said he was exposed to some of this at his previous school, but “coach Curtis definitely takes it to another level.”

“If we can make our athletes happier, healthier and just better functioning as humans, that’s huge.”

In the team’s performance center packed with weight machines, cameras and computers, a single leap into the air can produce 250 variables. At practice, small devices affixed to players’ jerseys collect 100 data points per second. Rings on the players’ fingers record their sleep, heart and breathing rates, and temperatures.

Rings on the players’ fingers record how much sleep they get, changes in heart rates and breathing rates, and temperatures.

Then there are surveys that peek into an athlete’s well-being and mental health, an optical system that maps players’ bodies during yoga-like movements, and computers that alert Curtis if a player’s weightlifting mechanics suddenly look different.

The crush of data available “is mind numbing,” Kupperman said. “And then we try to make sense of it.”

That, in essence, represents the promise of data science. And making sense of it is what puts UVA at the vanguard for research into how digital data can optimize student-athletes.

But unlike a top-secret playbook, UVA is willing to share the broad overview of the data it collects and how it analyzes it, all with the goal of improving this emerging intersection of science and sport.

Ideally, Kupperman and Curtis would be part of an expansive research collective with their collegiate counterparts across the country. But not every school is keen on cooperation.

“People don’t like to talk about their technology and how they are using it,” Kupperman said.

“We’re willing to actually show the results. We tell people all the time if you want to collaborate with UVA and put data together, I have all the mechanisms. I can get all the data agreements in place. And I will do all the legwork. But people are like, ‘no thanks.’”

So for now, the two are largely going it alone. And they are using men’s basketball as the proving ground for fast-emerging science and ever-changing gadgetry to assist other UVA sports programs.

“I’ve prided myself on being a beta site for sports science,” Curtis said, “so that, hopefully, what we have been able to do from a research-and-development standpoint will help other sports accumulate the technology that’s going to help them and that’s not going to waste their time.”

Curtis, a former four-year UVA basketball player and team captain, began dabbling in data not long after Bennett hired him 14 years ago.

“We decided to go down the route of using technology to make better informed training decisions,” said Curtis, who has two degrees from UVA and is working on a third. “Here we are, eight, nine, 10 years later with a lot of data streams coming in. We’re trying to utilize the data to help us in our decision-making for practices and training and everything.”

Kupperman is a sports scientist with a doctorate in kinesiology and sports medicine who served for years as an athletic trainer at Northwestern University and later UVA. In addition to teaching, she focuses on tapping into science to make the storied basketball program even more successful.

“Once you get to a certain level of sport, once you have all the skills and talent there, what’s the next thing that is going to move the needle?” she said.

Most days, moving the needle starts in the Good Stewards Basketball Performance Center, a sports-science lab stocked with weight machines, nutritional supplements, physical-therapy tables and a salt-water float tank, all just a short but meandering walk from the hardwood of John Paul Jones Arena.

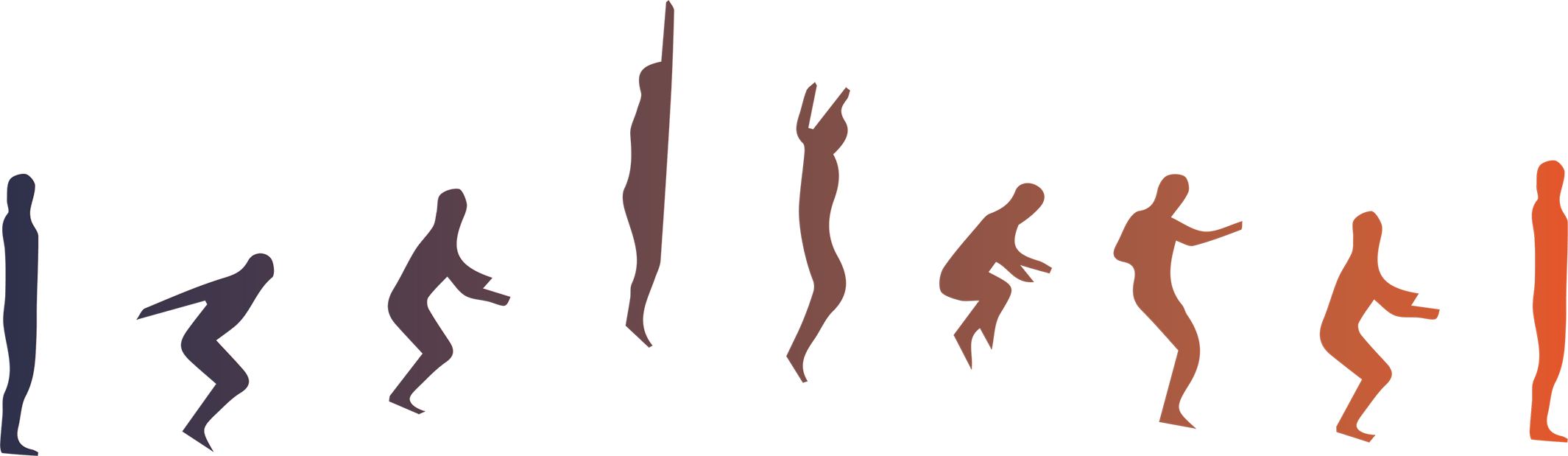

As often as three times a week, players file in, stand on pressure plates called “ForceDecks” embedded in the floor and jump as high as they can. Computers measure “flight time” and elevation but the data duo is more interested in how the players hop.

A rested athlete will bound into the air almost effortlessly, fresh legs like taut springs. A tired athlete loads slower, lower and maybe unevenly. The result – the height of the jump – is always about the same because “athletes are great compensators,” Curtis said. So the details come from the milliseconds before launch.

“So they’re going to make jump-strategy changes to achieve the same vertical displacement,” Kupperman added.

“And how they make those changes in their body to deliver that height is what we’re looking at.”

A longer load of the legs – graphed in green on a big-screen TV – signals some weariness.

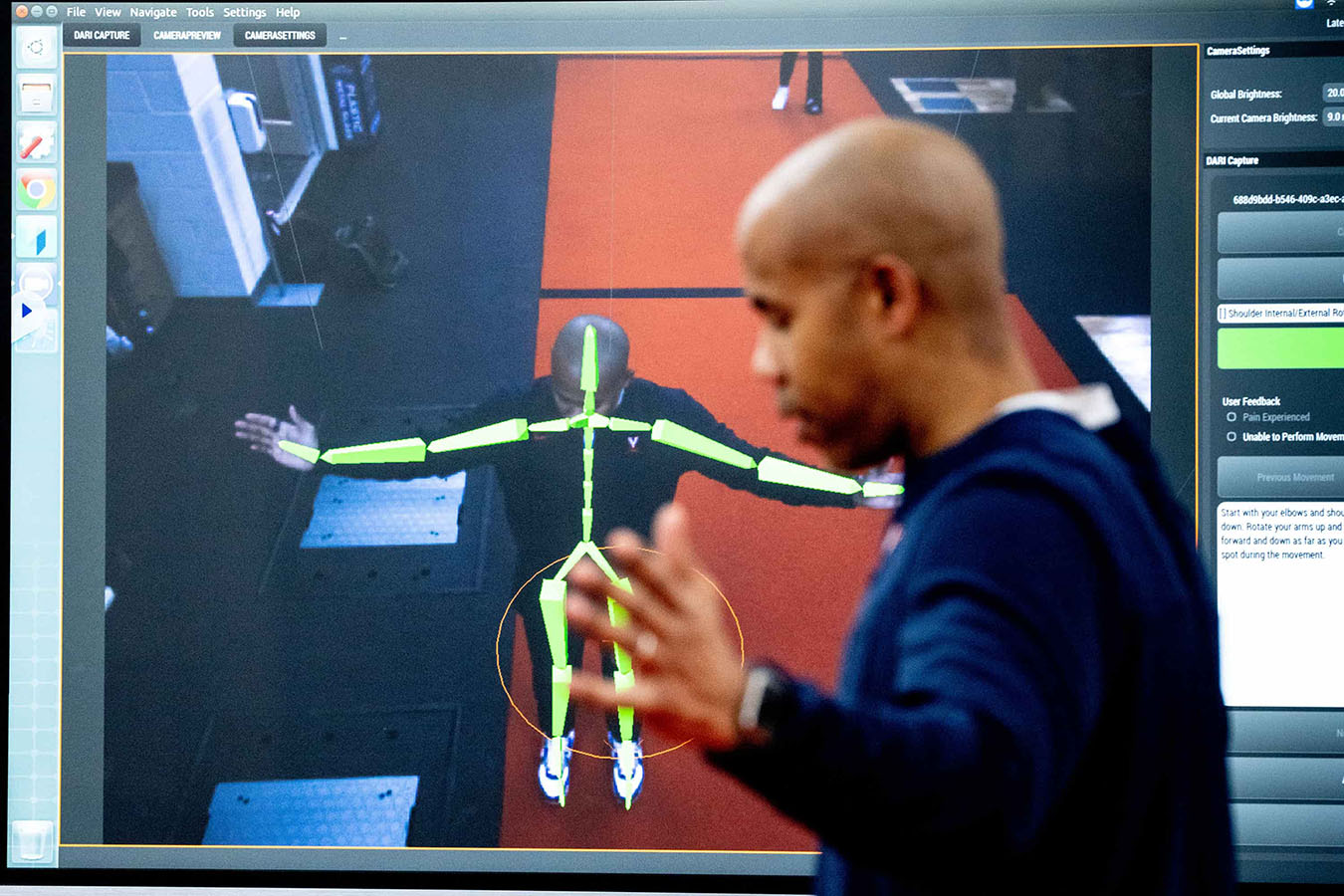

Just above the ForceDecks is a bank of cameras mounted to a metal frame suspended from the ceiling. The cameras size up each player as Curtis guides him through a series of 12 yoga-like movements.

Once a month, players drop into a lunge, twist their torsos, stretch their arms overhead and behind their backs, hop on one leg and then two. The DARI Motion optical system creates what looks like a video X-ray, bones and joints converted to neon green lines.

The computer compares a player’s movements to the same series a month earlier, noting changes. Sometimes the changes are good because the player has gained more flexibility or has recovered from an injury. Sometimes the changes are worrisome, an indication that a joint might be on the verge of damage, even if the player doesn’t yet know.

Later, the players head to afternoon practice with a gadget called a Catapult attached to their jerseys and centered between their shoulder blades. It’s about the size of a car-key fob and houses an accelerometer, gyroscope and a magnetometer.

But in the time between the weight room and the hardwood – when the players are in classes –Curtis and Kupperman crunch the numbers. From the computers and cameras, from the psychological assessments, from Oura rings tracking vital statistics, the data output is designed essentially to answer one question:

How hard can Bennett push the players in practice?

“I never tell the coach what to do,” Curtis said. “It becomes a negotiation just based on what we’re seeing in the data in terms of trends. I have this conversation with the coach about what would probably be the best duration and intensity of the drills that he’s going to pick for that practice session.”

Each day is a give-and-take.

“There are certain things he needs to get done” in practice, Curtis said of Bennett. “So sometimes we will skim a few minutes off a section here and there which, in the end, reduces the total time the athletes are under stress.”

With an adjusted practice plan in place, the second data dump begins.

“I never tell the coach what to do. It becomes a negotiation just based on what we’re seeing in the data in terms of trends.”

When players trot onto the floor, the Catapult devices measure every sprint and stop, leap and landing, cut to the left and cut to the right. A staff member keeps track of the drills like a court stenographer.

The Catapult data reveals unexpected results, like playing basketball half court is harder on the players than full court.

“When you think of what is hard versus what is easy, we tend to think, ‘Oh, full court is going to be much harder,’” Kupperman said. “What we really see from a workload perspective is that half court can be more challenging. It’s a higher volume of changes of direction, which has a larger impact on joint and muscular stress.

“That’s surprising to some people.”

The ultimate measurement from the Catapult device is called “external load” or “workload.”

“That is, biomechanically, what are we imposing on them in terms of stress,” Curtis said. “Not necessarily to the joint level, but the whole-body level.”

“A lot of people understand running miles,” Kupperman said. “And if you are a runner, your workload may be measured in miles. But in basketball, the workload is different because you are never really in a steady state of running. These special sensors give us a more specialized look at sports-specific workload or stress.”

“But,” Curtis added, “we never say this is a measurement of how hard you are working. It’s the volume of work.”

And, he said, it’s never a punitive tool. Coaches don’t ask which player’s heart rate is higher and which is lower, and no one tries to equate that to who is working hard and who is phoning it in. Besides, Kupperman said, science doesn’t support such a stripped-down conclusion.

That hasn’t stopped others from trying.

In 2018, the women’s basketball team at Texas Tech University was investigated for, among other things, using the heart rates of players as an indication of hustle, and punishing those whose pulses dipped in games.

It was part of what players described as a toxic team culture, and it made national news. It would never happen at UVA, Kupperman said.

“The players have consented to every technology and how we are using it,” she said. “And I pride myself on that. Not everyone does that.”

At the professional level, the ownership of biometric data is negotiated with players’ unions and fleets of attorneys, but “college athletes don’t have that,” Kupperman said. “There’s no one looking out for their best interests in these technologies right now. So Mike and I really made sure we are being forthright with the athletes. At any time, they’re allowed to say no to any technology, and that has no effect on their relationships with coach Bennett and the team.”

The sweet spot, according to Curtis, is pushing players hard enough to make them stronger, better and more resilient. But not so hard that “we dig them into a deeper hole, in terms of fatigue.”

And for a student-athlete, fatigue is more than just being worn out in practice.

“We have to account for all these other stressors that are being imposed on these student-athletes, because the body can’t differentiate stress,” he said. “The stress from playing, from social lives, from academics, from everyday things, it still has the same impact in terms of how we accumulate fatigue.”

Vander Plas, the graduate transfer, said the value to him is understanding what kinds of rest he needs to be at his best on the court. “Sleep is a big thing for me, and for coach Curtis to have all that data, and for me to be able to talk to him about it, that helps me recover in the best way possible,” Vander Plas said. “He looks at all the data and makes recommendations. And he’s been able to do this for the entire team. It’s really amazing and I think it has been really, really helpful for us.”

Unlike some of her UVA research colleagues, Kupperman isn’t swimming in grant money. The government doesn’t put many dollars into sports science, “and I agree with that,” Kupperman said.

The only government agency that seems intrigued is the Department of Defense. “They are very interested in the musculoskeletal health of their warfighters,” she said. But “DOD money is hard to come by.”

Some research is coming from athletic-apparel companies dabbling in adding data trackers to clothing. “And then there are private folks, the Mark Cubans of the world,” she said. Cuban is a multi-billionaire businessman and the owner of the Dallas Mavericks professional basketball team.

“He’s invested a lot of money in companies that do this work,” Kupperman said. “If Mark Cuban is reading this article and wants to donate some money to us, we’ll happily take it.”

But even without a pipeline of grant money, Kupperman and Curtis say the results of this science-and-sport partnership are clear on the court and in the classroom.

“I feel like that if you’re not utilizing this, you are a step behind.”

“The study of sports science and analytics has benefits across multiple fields” at UVA, Kupperman said. “That includes data science, orthopedics and sports medicine, physiology, and engineering. While the typical person is not a college or elite athlete, our goal is often to find ways to extrapolate our results to advance areas of musculoskeletal health and fitness. That has a significant impact on society.”

Since Bennett was hired at UVA, and since Curtis began a focus on using data to improve team performance, the Cavaliers have won two Atlantic Coast Conference tournaments and a national championship. This month, the Wahoos are once again gearing up for another tournament run.

And, for the fortunate few Cavaliers who head to the NBA, they’ll already have experience with sports data.

“In the feedback we’ve gotten from a lot of franchises that have drafted our athletes, or signed contracts with them, they are better prepared for the sports science that most professional sports want to employ,” Curtis said. “Our guys have already been exposed to it.”

“I feel like,” Vander Plas added, “that if you’re not utilizing this, you are a step behind.”

But just as important are the players who won’t go pro, Curtis said. He wants them leaving UVA with healthy and sound bodies undamaged from their years of college basketball. And this marriage of sports and science helps accomplish that, he said.

“After all,” Kupperman added, “you can’t play basketball forever.”