Christopher Ali was in just his second year of teaching an introductory media studies class when the table he was sitting on in front of the class suddenly broke in half and caused him to tumble to the floor.

So there was Ali, in a lecture hall with about 300 University of Virginia students, lying flat on his back.

For a young professor just starting out, the moment could have been deflating.

But for Ali, a former competitive figure skater accustomed to both successes and failures on some of the sport’s biggest stages, the sequence of events felt, well, strangely natural.

“I joke with my students that the thing that falling in front of 20,000 people teaches you is that it’s not a big deal to fall in front of 20,000 people,” said Ali, with a laugh. “I say, ‘If I can fall in front of 20,000 people, I can certainly get up in front of 300 and lecture in media studies.’”

The mindset has served Ali well.

Media studies professor Christopher Ali has become a leading voice in the quest for rural broadband equality. (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

Whether navigating the cutthroat and sometimes cruel world of competitive figure skating, coming out to his parents as gay or standing up for the rights of people in rural areas across the country who are suffering from the lack of internet access, Ali approaches everything he does head-on.

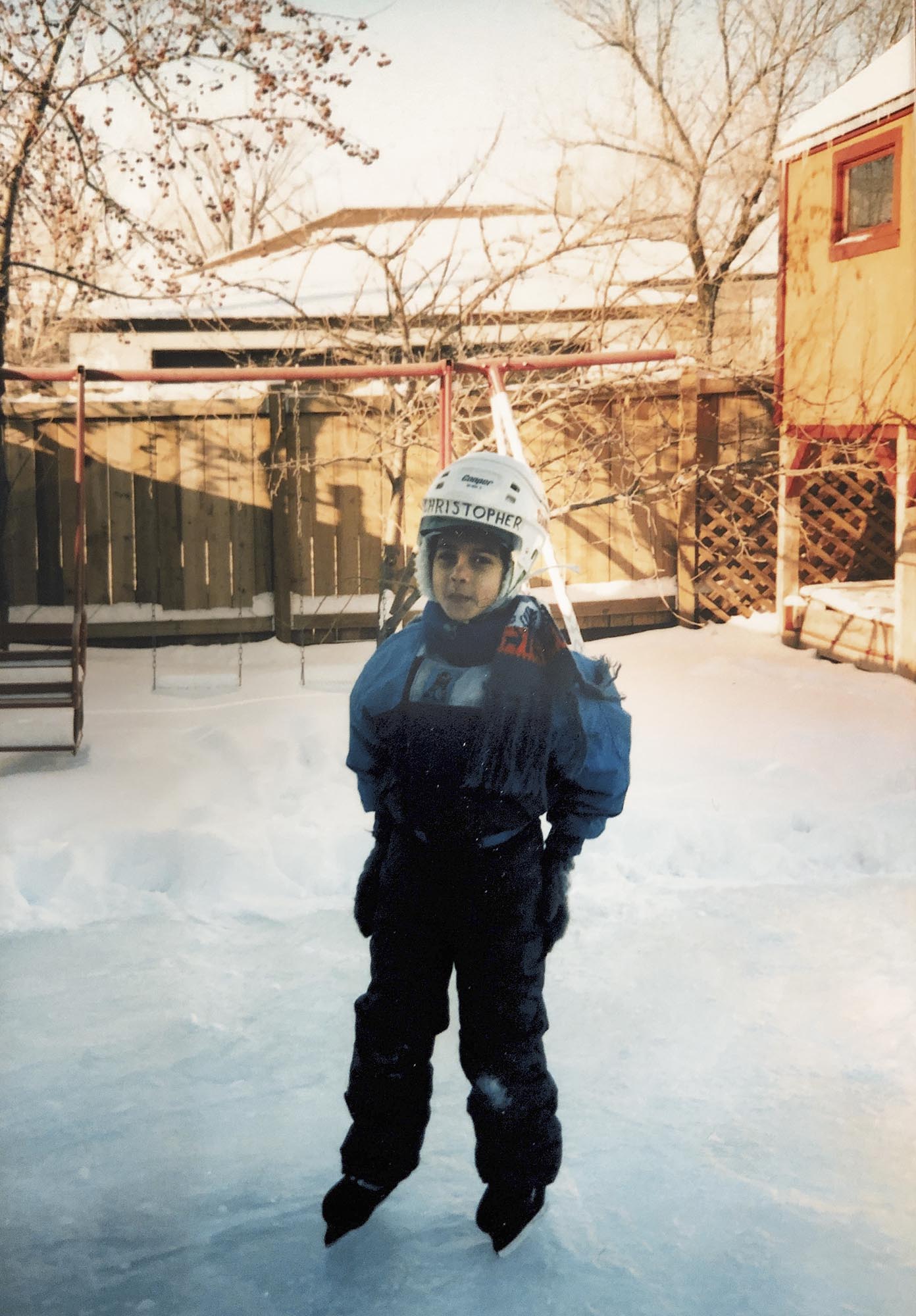

Born in Winnipeg, Canada, Ali started skating at the age of 2. His parents, Ray and Elaine, recall taking him to Duck Pond, an outdoor skating venue near their home.

Almost immediately, and without prompting, Ali started twirling.

A few years later, Ali sat mesmerized in front of the television as Canadian figure skating star Kurt Browning competed at the 1988 Winter Olympics in Calgary.

Unlike his younger brother, Jonathan, Ali didn’t participate in a lot of team sports.

“He was a God-awful soccer player,” Ray Ali said, laughing. “Figure skating was his only recourse.”

“He loved to perform,” Elaine Ali added. “His stage was the ice.”

Ali first started skating on a pond near his family’s home in Winnipeg when he was 2 years old. (Contributed photo)

Ali himself agreed.

“I think, quite frankly, I wasn’t very good at any other sports – not that I was very good at figure skating at the time, either, but it was something I enjoyed,” he said.

After standing out in a local learn-to-skate program at the age of 6, Ali came under the tutelage of a coach, Laurie Reade, who he would wind up working with for the majority of his career.

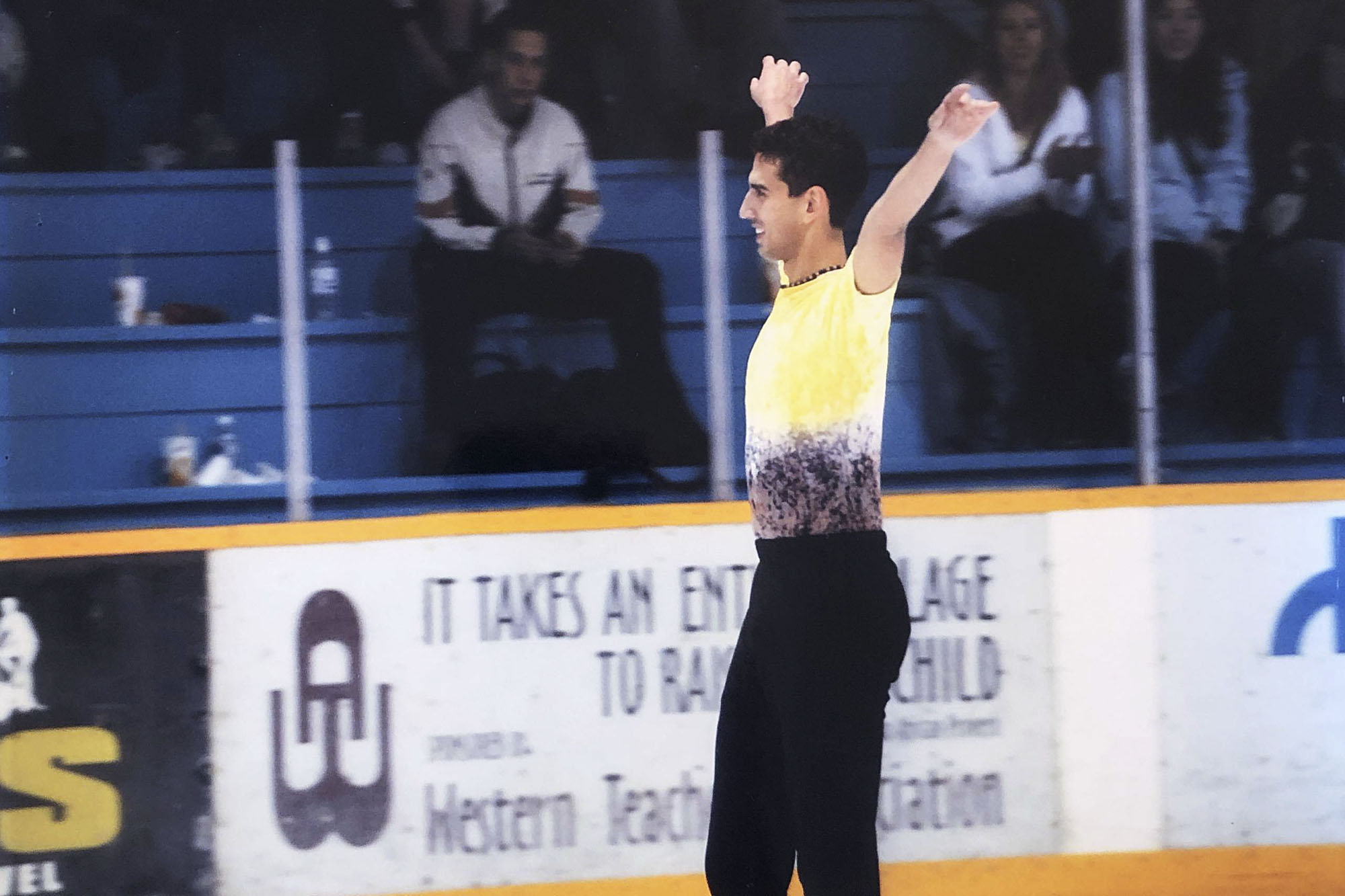

By his early teens, Ali had become known as one of the better skaters in the area; his breakthrough occurring when he won the Manitoba Championships as a 16-year-old.

“The great thing about being a guy in figure skating in a small province is that you get a taste of advancement pretty quickly because there were just so few boys doing it at that point,” Ali said. “You sometimes end up being the only person in your category. … You get noticed faster than if you are a girl who has to work that much harder to stand out from the pack.”

By the time he was 18, Ali was definitely standing out.

Heading into the Western Canadian Championships, he was a favorite to qualify for the Canadian Junior National Championships. Having trained hard, Ali was optimistic – but wound up having one of his worst performances.

“It turns out that I choke under pressure – or did,” said Ali, with a chuckle.

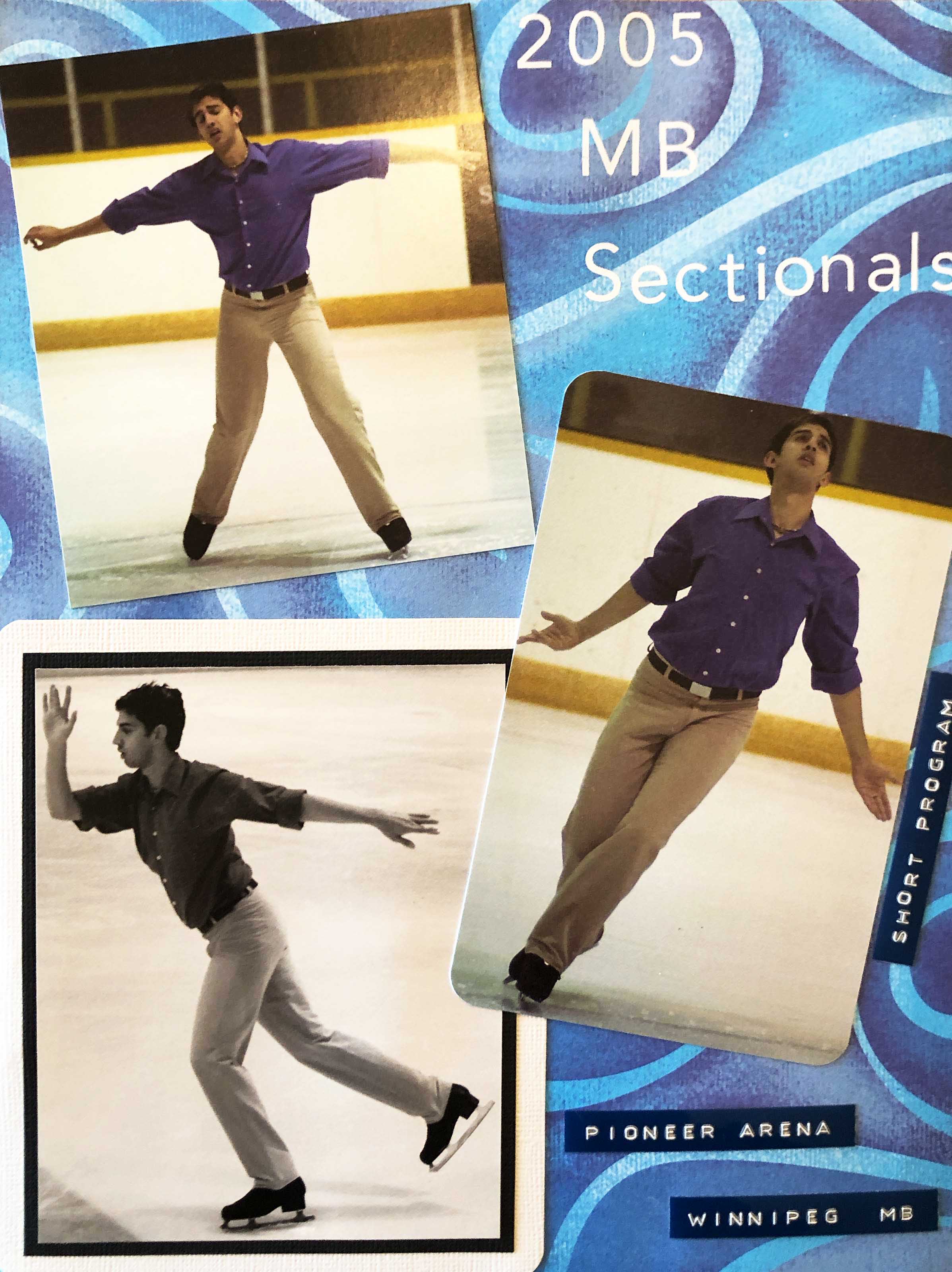

At the age of 6, Ali started working with a coach who had taken notice of his skating abilities. (Contributing photos)

At the time, Ali was devastated, but four weeks later he made it in as an alternate after another skater was injured.

The only catch was Ali had to make it from Winnipeg across the country to Hamilton, Ontario, in 24 hours. After a mad dash that included catching a last-minute flight and changing into his skating attire while in the car, Ali made it to the arena just in time.

Competing in the men’s short program, Ali didn’t skate particularly well, yet the experience provided an unforgettable memory. During the event, Ali was eating in the athlete’s dining area when Elvis Stojko – a three-time world champion and two-time Olympic silver medalist – sat down next to him.

“He told me how cool it was that I got to be there, and how awesome it was that I had kept training – even though I didn’t have a guaranteed spot,” Ali said.

Ali was as motivated as ever.

Growing up, Ali gravitated to figure skating rather than team sports like soccer. (Contributed photo)

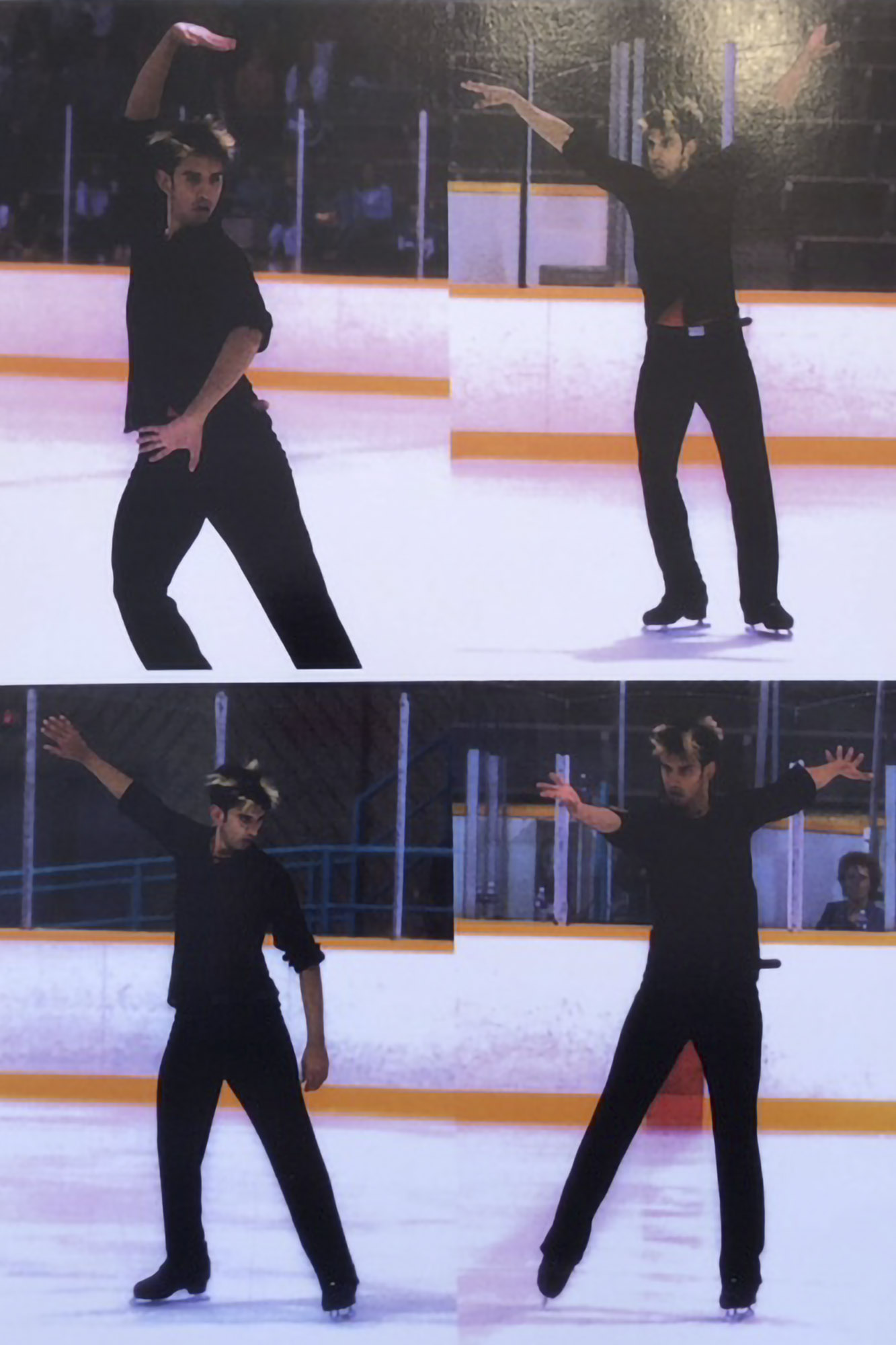

Wanting to push himself to the next level, Ali decided he needed to leave Winnipeg, which was known more for producing good curlers than figure skaters. In 2002, at the age of 19, he moved to Edmonton to train under Jan Ullmark, a former Swedish national champion who would later coach Canadian stars Jamie Sale and David Pelletier to Olympic gold medals.

That summer, Ali began competing in the senior ranks against other Olympic hopefuls. It was a tough go.

“My coaches used to say that I would ‘win the practices’ and really wow some people, and then I would get in the competitions and just couldn’t put it together,” Ali said.

On many occasions, Ray Ali paced the arena concession stands, too nervous to watch his son perform.

“Figure skating is such a difficult sport to watch when you’re attached to someone competing in it, because it’s like two or three or four minutes of just anxiety and stress,” said Jonathan Ali, who spent many hours in arenas cheering on his older brother. “You want them to hit every jump.

“We were on the edge of our seat every time he was out there.”

Ali made a deal with himself when he was a teenager that he could only continue to skate if he got good grades in school. (Contributed photo)

It wasn’t until he grew older that Jonathan Ali – who played baseball at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley – realized the mental hurdles his brother was facing.

“The thing that always got me so worked up with skating was that it was such a judgment sport, and sometimes so subjective in the judging process,” he said. “I couldn’t imagine how difficult that was. For me, it was either you scored more than your opponent or you didn’t. It was pretty easy to evaluate wins and losses that way.

“With skating, I just can’t imagine how exhausting it would be to deal with that kind of judgment as a 15-year-old, a 16-year-old in a sport like that. It just has to be mentally draining.”

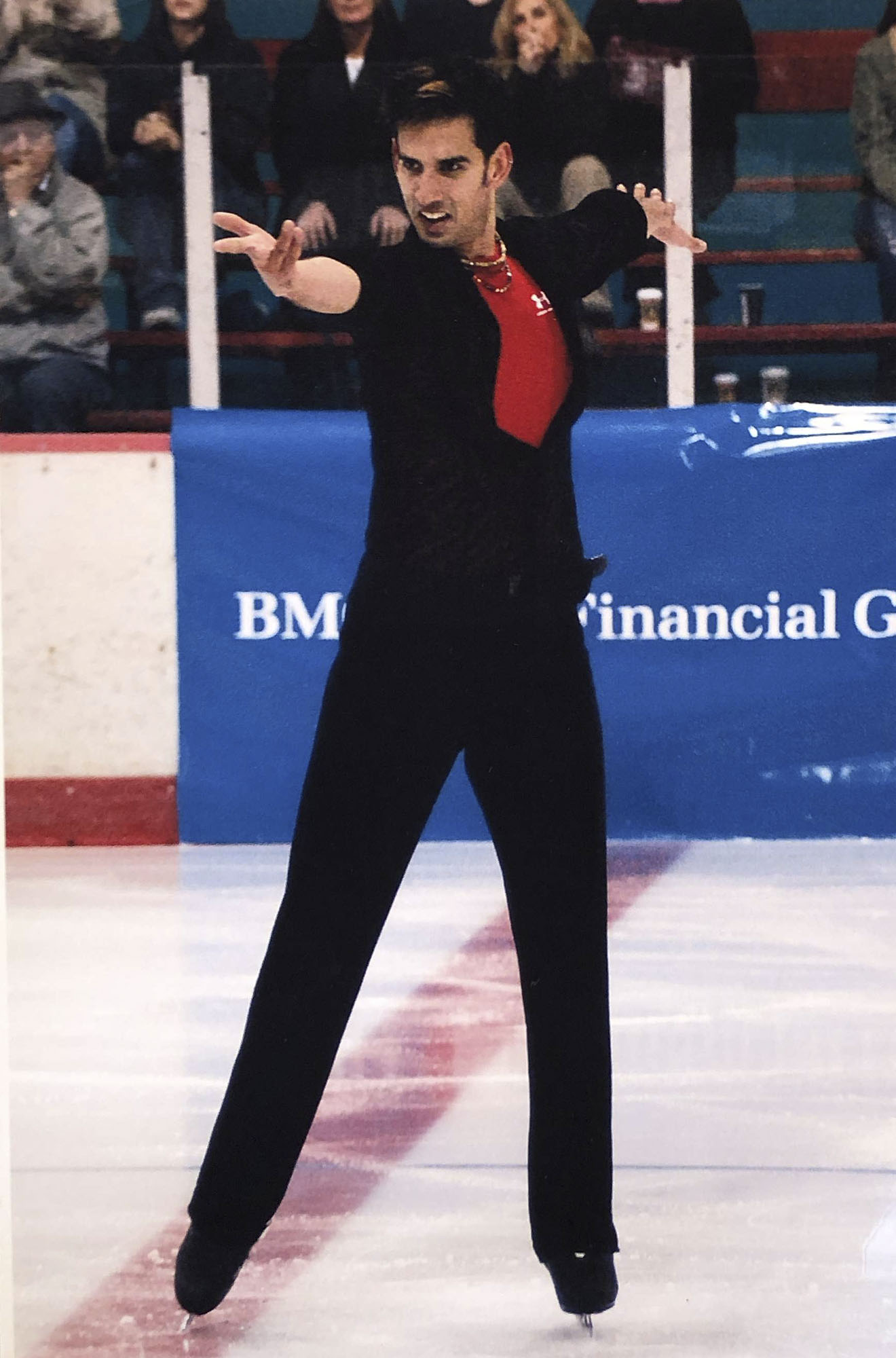

At one event, Ali had dyed part of his hair blonde. A judge called him a “badger” (not meant as a compliment) and told him that if he ever did it again, she would refuse to let him on the ice.

But Ali said one of his lowest moments occurred at the 2004 Canadian Championships in Edmonton. There, Ali placed higher than he ever had before, yet an article in an Edmonton newspaper suggested that he may as well quit if he wasn’t going to make it to the very highest reaches of the sport.

Ali still recalls the headline of the piece: What was the Point?