Ideas matter to University of Virginia politics professor John M. Owen IV.

“Many scholars in the field really don’t talk about ideas,” said Owen, the Ambassador Henry J. and Mrs. Marion R. Taylor Professor of Politics, and a senior fellow at the Institute for Advanced Studies in Culture and the Miller Center for Public Affairs.

“International relations for them is about material power – weapons, ships, soldiers, technology or money. And ideas really aren’t a part of this picture, except in a trivial way. I’ve always thought that’s wrong. Ideas do matter,” he said. “The notion that politics is just about who has the most guns has never been satisfactory to me – it’s also who’s got the words and the ideas.”

Owen hones his viewpoints by discussing them with colleagues, such as Dale Copeland, the Hugh S. and Winnifred B. Cumming Memorial Professor of International Affairs, who often disagrees with him.

“Despite different starting points, John and I enjoy long conversations on how to explain burning issues, such as why Putin went into Ukraine; the role of Chinese pressure on Russia, if any; and most importantly, how both internal and external factors can be combined into a good explanation for great power behavior through the centuries,” Copeland said. “John represents the best of international relations scholarship in that he both puts forward new arguments of his own but remains open to the way factors outside his own approach might either qualify his findings or extend his argument in new directions.”

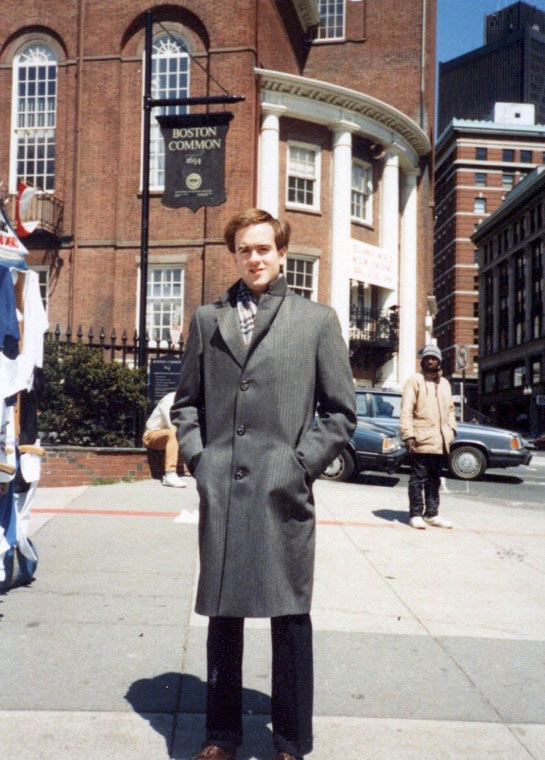

Owen, who received a bachelor’s degree from Duke University, a master of public administration degree from Princeton University and a Ph.D. from Harvard University, was introduced to politics as a child at his family’s supper table in Raleigh, North Carolina. His father, a United Methodist minister, was “publicly engaged.”

“I grew up in the 1960s and 1970s and we had the ABC Evening News with Peter Jennings on,” Owen said. “We would talk about what was going on. I remember the Vietnam War as a kid and asking my father what was up with that. It was part of the family discourse.”

His appetite was whetted more in college when a mentor, a mathematical demographer, took Owen to Vienna as a research assistant and he met counterparts from the Soviet Union.

“I was getting to know people from communist countries,” he said. “This was in 1984, five years before the Berlin Wall fell. And I found it really invigorating and important, interacting with these people, trying to figure them out.”

“The Russians were quite constrained,” Owen recalled. “A group of us started talking about their war in Afghanistan, fighting a war kind of like our Vietnam War, and they reached a point where they said, ‘We do not say anything. We agree with our country,’ or something like that. What they were really saying was ‘Please stop pushing us on this.’ That really struck me. I couldn’t have an honest conversation with someone because of politics, because they live under this regime where, while maybe they would like to speak frankly, they can’t do it.”

The book, not the year, “1984” is also significant to Owen, who first read George Orwell’s dystopian warning when he was 12.