Editor’s Note: Nathaniel “Nat” Howell, John Minor Maury Jr. Professor Emeritus of Public Affairs at the University of Virginia and the U.S. ambassador to Kuwait during the 1990 Iraqi invasion, died Dec 17 after suffering a stroke. He was 81. Howell earned two foreign affairs degrees from UVA; a Bachelor of Arts in in 1961 and a Ph.D. in 1965. After his diplomatic career, Howell returned to UVA, where he directed the Institute for Global Policy Research and the Arabian Peninsula and Gulf Studies Program. He and his wife Margie, who earned her nursing degree at UVA in 1960, were instrumental in establishing the Rouhollah Ramazani Professorship of Arabian Peninsula and Gulf Studies at UVA, as well as two other endowed funds. Howell’s papers, dating from 1947 to 2001, are held in UVA’s Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library.

UVA Today originally published this profile of Howell in August, on the 30th anniversary of the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait.

On Dec. 7, 1990, ABC News anchor Peter Jennings opened his broadcast with a revelation: After four months of sheltering in the U.S. embassy in Kuwait following Iraq’s invasion, the few remaining American diplomats there were preparing to return to the United States.

The United States had decided to close the embassy, which had been surrounded by Iraqi troops, saying that with most U.S. citizens having escaped the overrun country, American’s diplomatic mission was complete.

Leading that effort was Nathaniel “Nat” Howell, a career diplomat. Educated at the University of Virginia, along with his wife Margie, in the 1950s and ’60s, the pair returned to Charlottesville in the 1980s, as both of their sons enrolled at the University. Appointed by President Ronald Reagan, Howell then served as ambassador to Kuwait from 1987 to 1991.

After returning to private life, Howell, now the John Minor Maury Jr. Professor Emeritus of Public Affairs, directed UVA’s Institute for Global Policy Research and its Arabian Peninsula and Gulf Studies Program.

Sunday marked the 30th anniversary of Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait, after Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein accused the Kuwaitis of stealing Iraqi oil by slant drilling under the border.

Howell and Margie were recently interviewed about their time in Kuwait by Dr. Greg Saathoff, a professor of emergency medicine and public health sciences at UVA who also serves on the board of directors of UVA’s Colonnade Club.

A video of the interview was shown at the club last Friday and was followed by a live question-and-answer period. Here are some highlights from the presentation.

Q. Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait 30 years ago, on Aug. 2, 1990. Where were you when you heard the news?

Margie: I had come home the week before. I was here in the States, in Virginia.

Nat: We had a rather early evening. About 11 o’clock, I went to bed, and about 2:30, I was waked up, saying they were coming across the border. We had a secure phone to Washington, so, I got in touch with Washington and said that the Iraqis were invading, because it was a night and we had spy satellites, but we couldn’t see them at night.

Smoke from munitions wafts thru the air in front of the U.S. Embassy, which sits across the street from the Kuwait International Hotel.

We realized that by that time, the Iraqi forces on the ground were behind Kuwait City. Because we have these marvelous highways that would take you zipping down and been built by the (U.S.) Federal Highway Administration, we began to see armor and all in town. We told everybody not to panic, but to come to the embassy and bring as much food as they can carry and private possessions.

Q. The embassy was not grand by any means. Can you describe it?

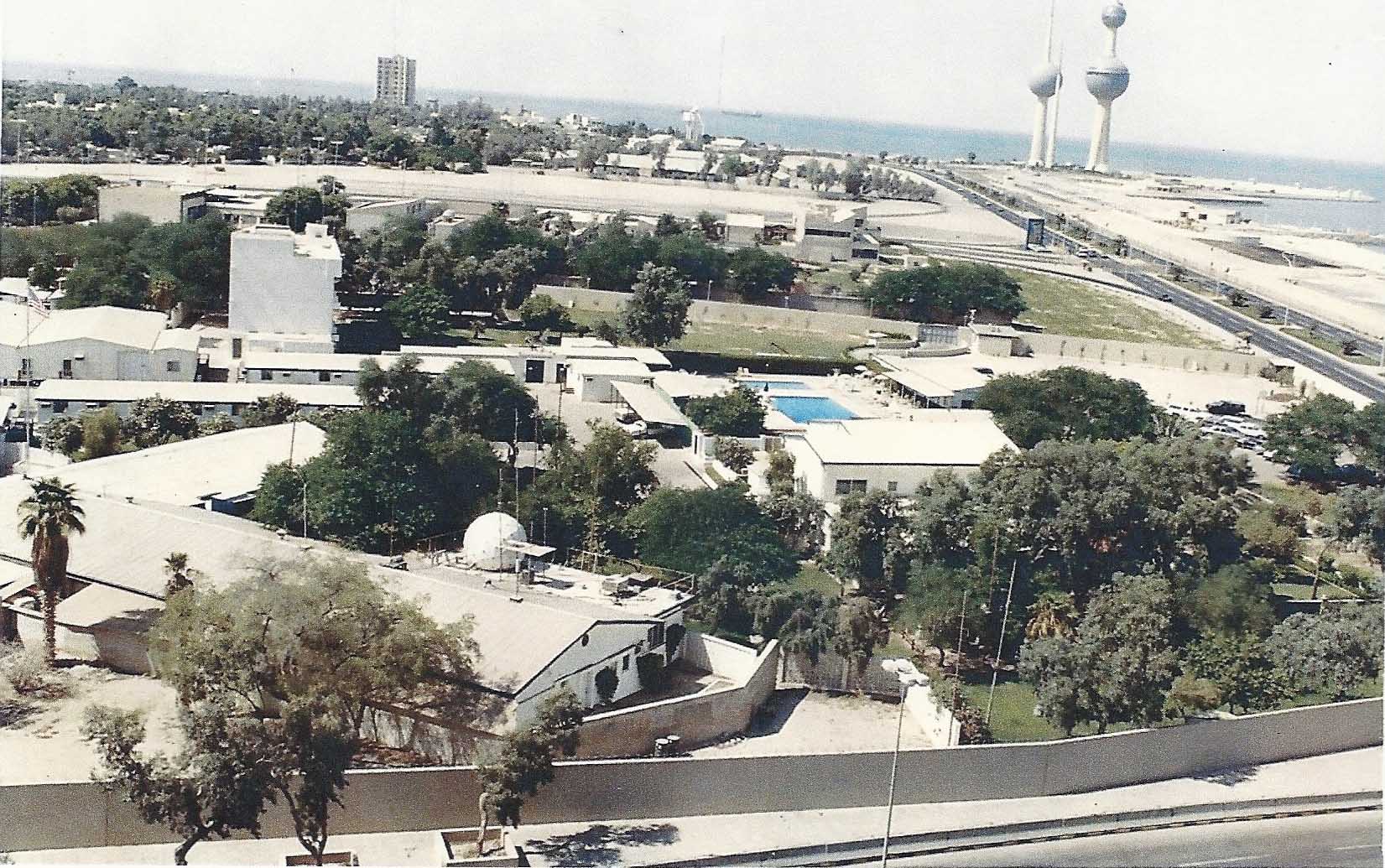

Nat: Well, I have a great fondness for it because a lot of the features that are so unattractive really helped us survive. It’s on five acres. As a result of a truck bombing in the early ’80s, I had a 9-foot wall around it with razor wire on top of it. And then there were a bunch of sort-of prefab buildings; some of them were not even permanent buildings. And the inspectors who came through said it has the aura of a well-maintained boys’ camp. But it was our place and refuge and it served us well.

Q. Not having social media, how were you able to communicate with American citizens living in Kuwait?

Nat: Well, we had a telephone tree. And a system of wardens who were from the community and in particular areas. Several days before the invasion, I had this meeting with the wardens and we asked them to check their telephone trees. … And it worked fairly well until the Iraqis cut our telephone. The three things you do are: warn your community; bring in your employees; and we offered to anyone who wanted it sanctuary in the embassy.

Q. What did you do with the classified information held at the embassy?

Nat: You begin destroying classified information and equipment. So, that went on for about three days. We ground up everything, including the Christmas card list.

Q. In that moment, how long would you have guessed everyone would be holed up in the embassy?

Nat: I would not have made a guess. And considering the situation, I didn’t see how we were going to get all these people out of here alive. I was afraid we’d have casualties.

Q. What contingency plans were made?

Nat: We made preparations for a number of things. We lined up cars in a convoy in case we got a chance to run to the to the Saudi border down south, which is the closest exit. We began laying in supplies so that we could survive. So we tried to foresee any particular circumstance that might come along and prepare for.

Q. What was your understanding of the Iraqis’ intent?

Nat: We didn’t know what their intentions [were]. They didn’t come to the embassy and say, “Look, we are occupying the country, but you’re OK.” … We didn’t quite know what to make of them. What we could do is monitor the fact that Kuwaitis, when they had a chance, were resisting. And we could tell Washington that there were no Kuwaiti traitors that we knew of that were in on this. The Iraqis tried to separate the opposition and all, and [the Kuwaitis] wouldn’t have it. So Kuwait more or less stuck together. They tried to create a government in exile.

Q. How would you describe the Iraqi forces?

Nat: I mean, let’s face it, most of these Iraqi troops, they didn’t want to be there either.

A lot of them were conscripts. There were some, like the Republican Guard, who were enthusiastic supporters. But a lot of these were farm boys and peasants who were conscripted and sent down there and treated like the devil. They were lucky if they came by with one bowl of rice a day.

We had a number of them come to the back of the embassy, to the gate back there, where we had a guard, and offer to turn in their guns and uniforms if we gave them civilian clothes and food.

Q. You had a famous visitor. The Rev. Jessie Jackson came to the embassy to help evacuate people. What was that like?

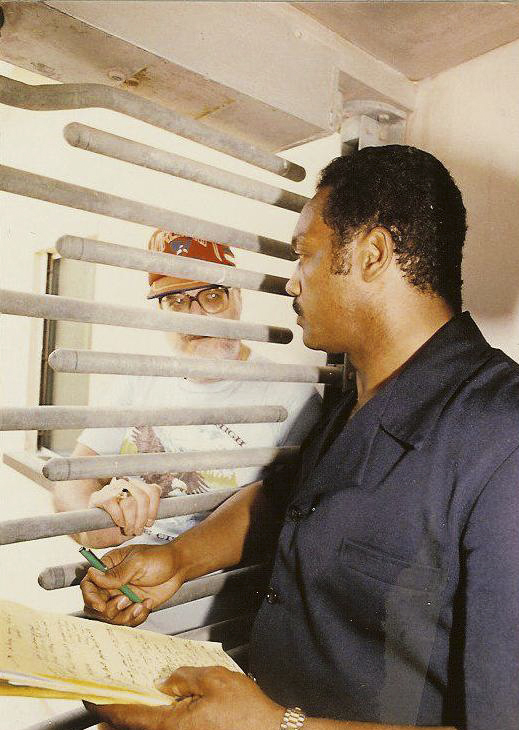

The Rev. Jesse Jackson is seen talking with Howell during a visit. Jackson helped facilitate 13 plane evacuations of U.S. women and children.

Margie: It was very helpful. He started the whole series of flights getting American women and children out.

Nat: We started operating flights, and of course, none of us in the embassy could leave to help people get on the planes. So, we had to recruit American wives or Kuwaitis and other people who knew their way around to get these people to the airport and through the airport customs onto the planes. I mean, it’s a miracle it worked. We nearly sweated blood that first flight, until we heard it had gotten past Baghdad. So, I guess during the time we were there we were able to run 13 of those flights.

Q. Tell me about when you learned you would be allowed to leave the country.

Nat: Well, we were listening to the news on a portable radio one morning and they said [Saddam] Hussein decided everybody could leave. I knew that was not definitive as far as I was concerned. So, we had to wait till that afternoon. And when I was talking to the [State] Department, I said, “We heard this on the radio,” and they said, “Yes, it’s true, it’s true. And we want you to lock the embassy, but don’t take down the flag.” I said, “Are you sure you don’t want me to stay?” And he said “No, no. We want you to come out after all the Americans have had a chance to come out.”

So that was, I think, on a Saturday. And we stayed to the following Wednesday or Thursday and ran two flights. I came out of the last one.

Ambassador Howell said that while not lavish, the embassy was sturdy and safe and “served us well.”

Q. Margie, how did you feel when you heard the news that Nat and everyone else was returning to the United States after four months under siege in Kuwait?

Margie: They were told they had to come out on Iraqi planes. So, first they fly to Baghdad and change planes there. Then they fly them in on an Iraqi plane to Germany. So, I did not feel he was safe until he landed in Germany, where he then took a long bath.

Nat: I brought a lot of Kuwait with me.

In mid-January 1991, a U.S.-led international coalition launched an operation to liberate Kuwait from Iraqi rule in what would become known as the first Gulf War. Two months later, the emir of Kuwait returned from exile to assume control of the country.

Media Contact

Article Information

August 4, 2020

/content/former-ambassador-kuwait-reflects-turbulent-iraqi-invasion-30-years-ago