Second in a series leading up to Friday's announcement of the 2015 Harrison Undergraduate Research Award winners.

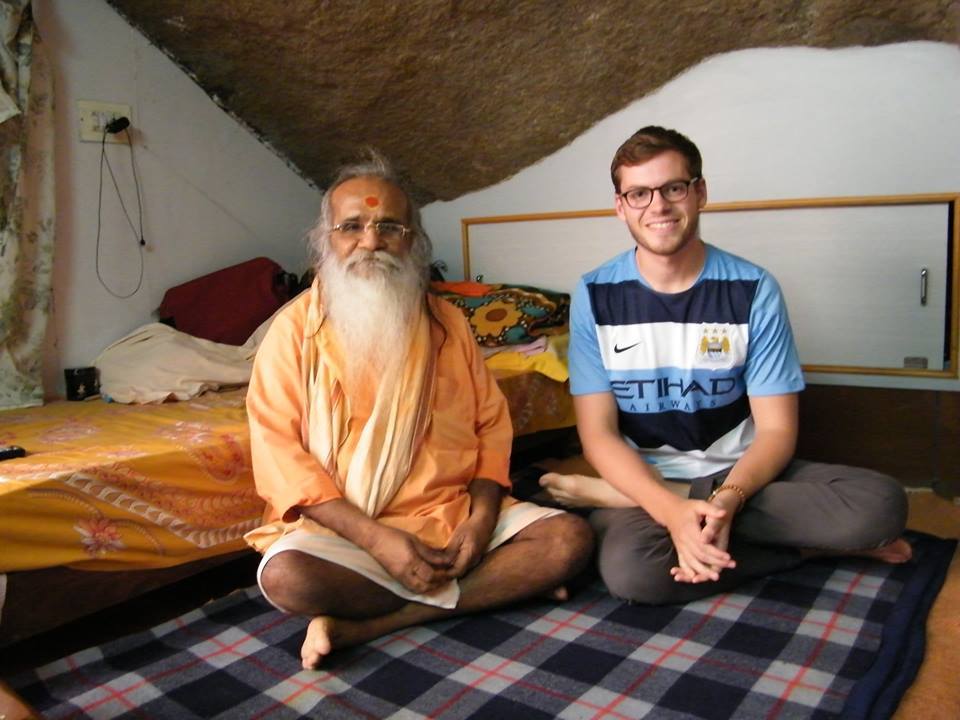

“Is this his first time here?” an elderly Indian man sitting in a hilltop cave asked, motioning toward third-year University of Virginia student Wade Oakley last summer.

When Oakley’s accompanying yoga instructor answered affirmatively, the swami, a religious teacher, smiled. “It won’t be his last,” he said.

Oakley, a commerce and cognitive science major, had just arrived in Mysore, India for the summer to research the teachings of the world’s most advanced Ashtanga yoga practitioners. With the help of a Harrison Undergraduate Research Award, Oakley had set out to study the social implications of group contemplative practice – the effect that learning among a community of yogis has on a participant’s experience.

Mysore is home to Ashtanga yoga, one of the most physically intense types of the practice, and serves as the central training point for all instructors who teach Ashtanga throughout the world. The Mysore-style practice is taught in a group setting, where participants go through a sequence of poses and breathing exercises at their own pace.

While most scholars focus on the withdrawal of the individual into his or her sensory focus when doing yoga with a group, Oakley theorized that even though the Mysore style is individualistic, the surrounding community is a source of support and power. This would suggest that there is a correlation between individual advancement and the communal yogic environment.

Oakley’s faculty adviser, John Campbell, an assistant professor of religious studies and a founding member of the U.Va. Contemplative Sciences Center’s executive board, said that the research was important because it could give readers new ways to think about the group benefits of yoga, its relation to religious studies and the way group contemplative practices can help even non-yogis.

“Pursuing this says something of real significance in terms of the study of religion,” he said. “Religious experience doesn’t work in a vacuum; it takes place within a community. That’s one of the things that we as scholars of religion seek to understand better.

“His project is interesting because he’s highlighting this shortfall in contemporary thought where you have a model in this tradition of contemplative practice that makes it clear that as the practitioners become more virtuous, they do thrive in group settings, but as they do so they become less dependent on their immediate environment,” Campbell said. “Wade has set up a sophisticated model for modern social facilitation theory and seeing whether that is applicable in this case, and whether they do benefit from group setting.”

Oakley got hooked on Ashtanga yoga after checking out a class offered at the North Grounds Recreation Center during his first year. For six days a week in the mornings, the Contemplative Sciences Center offers classes open to the entire University community and the Charlottesville community at large.

As he deepened his experience in both its strength building and spiritual calming, and learned more about the place where the practice originated, he was eager to find a way to get to India and study the practice at its origin.

Mysore was a perfect place to study the social effects of yoga because it was so ingrained in the culture. Oakley wasn’t just practicing yoga for two hours a day, but living it – studying Sanskrit, chanting and attending classes focusing on old yogic texts.

“In India, the idea of yoga would never be disconnected from the rest of the lifestyle,” he said. “What happens off the mat is more important than what happens on the mat. And that was something I could definitely appreciate learning there and being around those people.”

He’d come to the yoga institute with a checklist of questions for the teachers and students about what was going on in their heads during the yoga sequences, but he soon found that he might as well toss that approach off a cliff.

“I had this idea for getting some biological markers for what’s a good practice, how focused you are, but it was far too invasive for the setting I was in, because I wasn’t just an outside researcher – I was a practitioner and member of the community,” he said.

Instead, he had to sit down and listen to the practitioners he was interviewing, and figure out how to extract what he learned in their stories that could be useful for his research.

“I would get these incredible stories of spiritual experiences,” he said. “It came down to, ‘How do you go about describing the energy in the room, and the significance and presence of the guru, and how to you describe that without using those terms?’”

He said the experience helped him get a glimpse of what academia can be.

“Combining my coursework [in cognitive science] and academic interests with a passion outside of class was very cool and it’s something I think everyone can do,” he said. “It enriches both, and makes them more meaningful.”

As he continues his studies back on Grounds this year, Oakley is planning to use his findings to work with Campbell to publish one, possibly two journal articles, and he continues to lead U.Va. Ashtanga attendees at North Grounds.

He said his experience in Mysore is something he’ll always take with him.

“Now I’m figuring out when to schedule my next trip to India,” Oakley said. “Like Swamiji said, I’m going back.”

Media Contact

Article Information

March 23, 2015

/content/gaining-insight-india-uva-student-studies-yoga-communities