A United Nations intervention will send police officers from Kenya and several other countries into Haiti, a Caribbean nation of about 11 million people riven by deep political, economic and social strife.

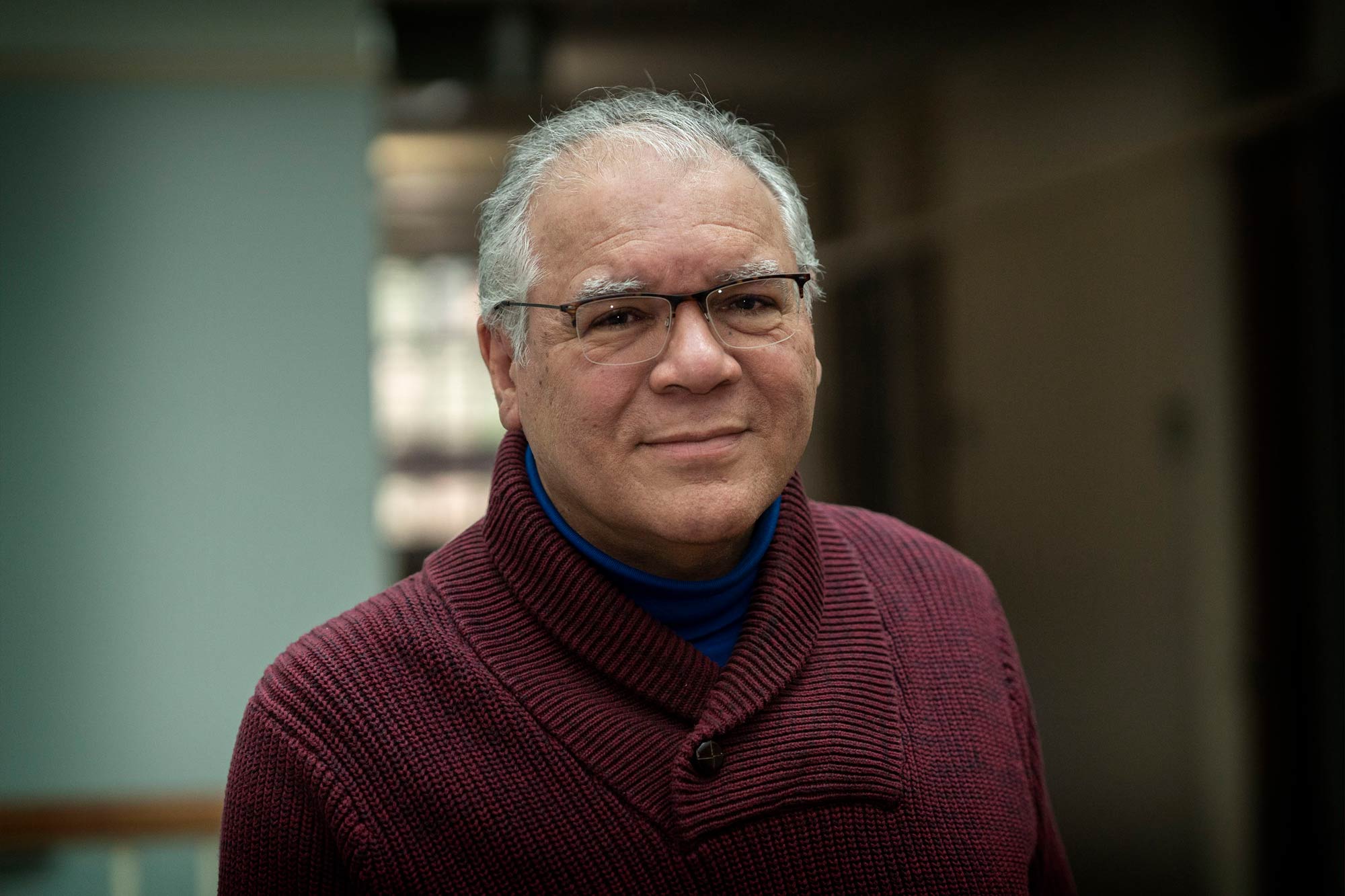

UVA Today sought some perspective from Haitian-born Robert Fatton Jr., the Ambassador Henry J. Taylor and Mrs. Marion R. Taylor Professor of Politics at the University of Virginia. He frequently visits the country, where his siblings and extended family reside. He is author of “Haiti’s Predatory Republic: The Unending Transition to Democracy,” “Haiti: Trapped in the Outer Periphery” and “The Guise of Exceptionalism: Unmasking the National Narratives of Haiti and the United States.”

Q. Who’s in charge in Haiti now?

A. The same Ariel Henry government that was put in power by the international community two years ago. In the last few weeks, the Kenyan government has agreed to send 1,000 police officers. A few Caribbean countries and some others such as Spain, Italy and Mongolia are going to send a few police officers or trainers.

That has been approved by the United Nations Security Council, but the Kenyan opposition has challenged the deployment and the Supreme Court of Kenya is looking at the issue. It appears that the constitution of Kenya prevents Kenya from sending police officers. It can send military people, but not police officers. I think the Supreme Court is going to say that is fine.

The Kenyan government is getting at least $100 million because Kenya and the United States recently signed a security agreement, using Kenyan troops for peacekeeping in Somalia. The United States couldn’t find anyone to send troops to Haiti. They tried the Mexicans, the Brazilians and the Canadians.

Q. Will it make a difference?

A. At best, they can reduce the level of violence in the capital city, but it’s not going to resolve any of the fundamental problems that Haiti has confronted for the last few years. The opposition in Haiti is not too keen on receiving the Kenyans. They are saying that if the Kenyans come, they will essentially prop up the existing government, which, in their eyes, is completely illegitimate.

The issues of poverty, massive inequalities, [and] infrastructural and political decay are not going to be resolved by the deployment of those Kenyan troops.

The Haitian government and the Kenyan government didn’t have diplomatic relations with embassies. Once the agreement was signed, there was a very quick move by the Haitians to set up an embassy and send an ambassador to Kenya. So this is very ad hoc.

I think it’s because no other countries want to go to Haiti. They know what happens with international interventions – they reestablish some security, they exit and the situation is worse. In the past, those international interventions were fraught with all kinds of corruption and sexual assault on the Haitian population.

When the UN was there until 2017, some of the troops introduced a strain of cholera that was unknown in Haiti. So Haitians are exhausted with the international community. And I think the international community, frankly, is exhausted with Haiti.

The gangs have expanded their control over Port-au-Prince, something like 60% to 80% of the capital city is essentially under control of the gangs. International intervention would have to secure access to the international airport, which is sometimes closed, sometimes not. The gangs control the roads leading to the airport and the oil depots, which means they can stop traffic and get money when they reopen the avenues.

The government is weaker than before, and they hope that the Kenyan intervention might help them. But we are not any closer to any type of election, or anything of that sort. And it would be impossible to have elections now in the current climate. And as far as I know, negotiations over an electoral council that will be acceptable to all those things are not going anywhere.

Q. Is this Haiti’s new normal?

A. This is the normal over the past probably five or six years. I don’t think that I’ve ever seen a crisis of this magnitude in Haiti, and we’ve had major crises. This is probably the worst situation we’ve had since in the early 1960s, when “Papa Doc” Duvalier was in power and you had massive killings of people in the country.

Now you have a government that is completely legitimate to no one. There’s no elected authority in Haiti. And the very fact that the gangs can control 60% to 70% of the capital city indicates that there is a complete vacuum of governmental authority.

Q. What do you see as the future for Haiti?

A. I’m extremely pessimistic. I’ve always been rather pessimistic, but not as pessimistic as I am now. When you look at the situation objectively, they are very few exits. You would need a government of national unity, and without it, you can’t go very far.

The international community wants to establish a modicum of security and wants to prevent an exodus of boat people. Poor Haitians hope they can get to the U.S. or even Mexico, find a job and then send remittances to their families – remittances that are basically the fundamental economic way that the country is surviving.

Foreign remittances represent something around $3 billion a year. This is more than the any type of foreign assistance, and this is how people function.

Media Contacts

University News Associate Office of University Communications

mkelly@virginia.edu (434) 924-7291