On Dec. 10, 1938, on the eve of World War II, Herbert Friedman boarded a train in Austria bound for England. It was the day before his 14th birthday. He joined nearly 10,000 children, virtually all of them Jewish, who were rescued from Nazi-controlled territory across Europe and taken to the United Kingdom.

Herbert eventually made his way from London to Maryland and went on to fight for the United States in World War II and the Korean War.

His son, University of Virginia alumnus Mark Friedman, has donated materials documenting his father’s remarkable life to UVA’s Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library.

Herbert died in 2020, leaving Mark and his two brothers (Gary and Ron, also UVA alumni) to tell their father’s story. The collection is still being processed, but Special Collections curators hope to make the materials available for research and instruction sessions soon.

“More than remembrance, to try and create a learning experience so that people can make a personal connection to this, is so important,” Mark said. “Most people aren’t faced with genocide in their daily lives. But we are all faced with decisions where we need courage or empathy. That’s what I want to accomplish in promoting my father’s memory.”

Herbert was a witness to Kristallnacht, a night of anti-Jewish terror that began Nov. 9, 1938, and led to the deaths of scores of German and Austrian Jews and the destruction of Jewish-owned homes, businesses, schools and synagogues. The next morning, he went to check on his family’s immigration status, where he was put on the list for the Kindertransport program. A month later, he was on a train bound for England. Only one family member could accompany him to the train station.

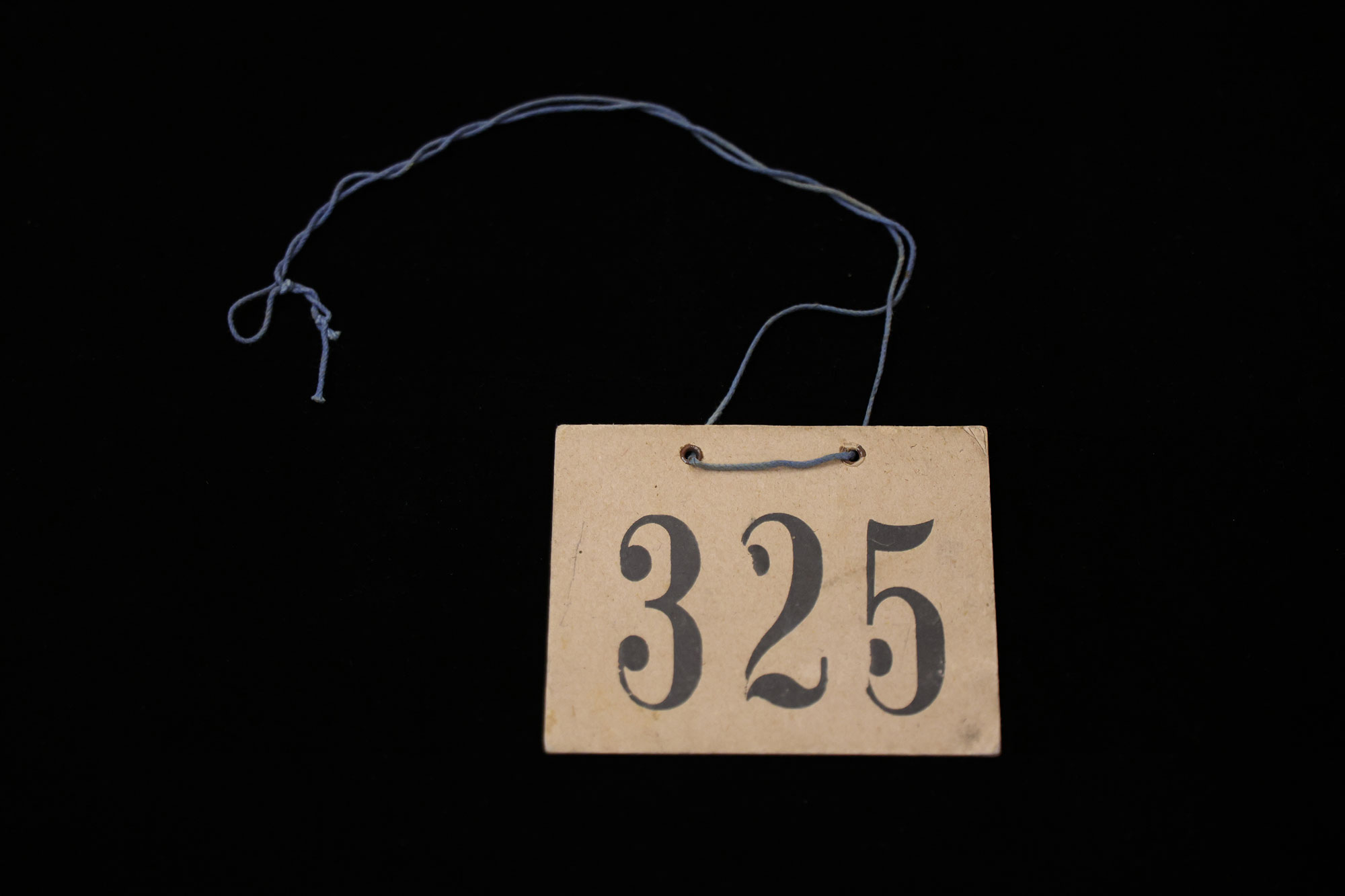

The cardboard tag Friedman wore on the train to England stands out for how well-preserved it is. (Photo by Matt Riley, University Communications)

Special Collections now has the cardboard tag Herbert wore on the train, his passport and a letter from the chief rabbi of England instructing the children to be on their best behavior as guests in England, among other items. It’s an impressive collection – Mark said the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington sought to acquire it – but Special Collections curators were struck by other details.

“One of the things we’re marveling at is that despite being a child in this prewar era and then the war starting to break out, he had the presence of mind to retain a lot of this material,” Special Collections curator Meg Kennedy said.

Still, Herbert was a child. In addition to his birth certificate and letters from family, he also smuggled a German translation of “The Three Musketeers,” a favorite book.

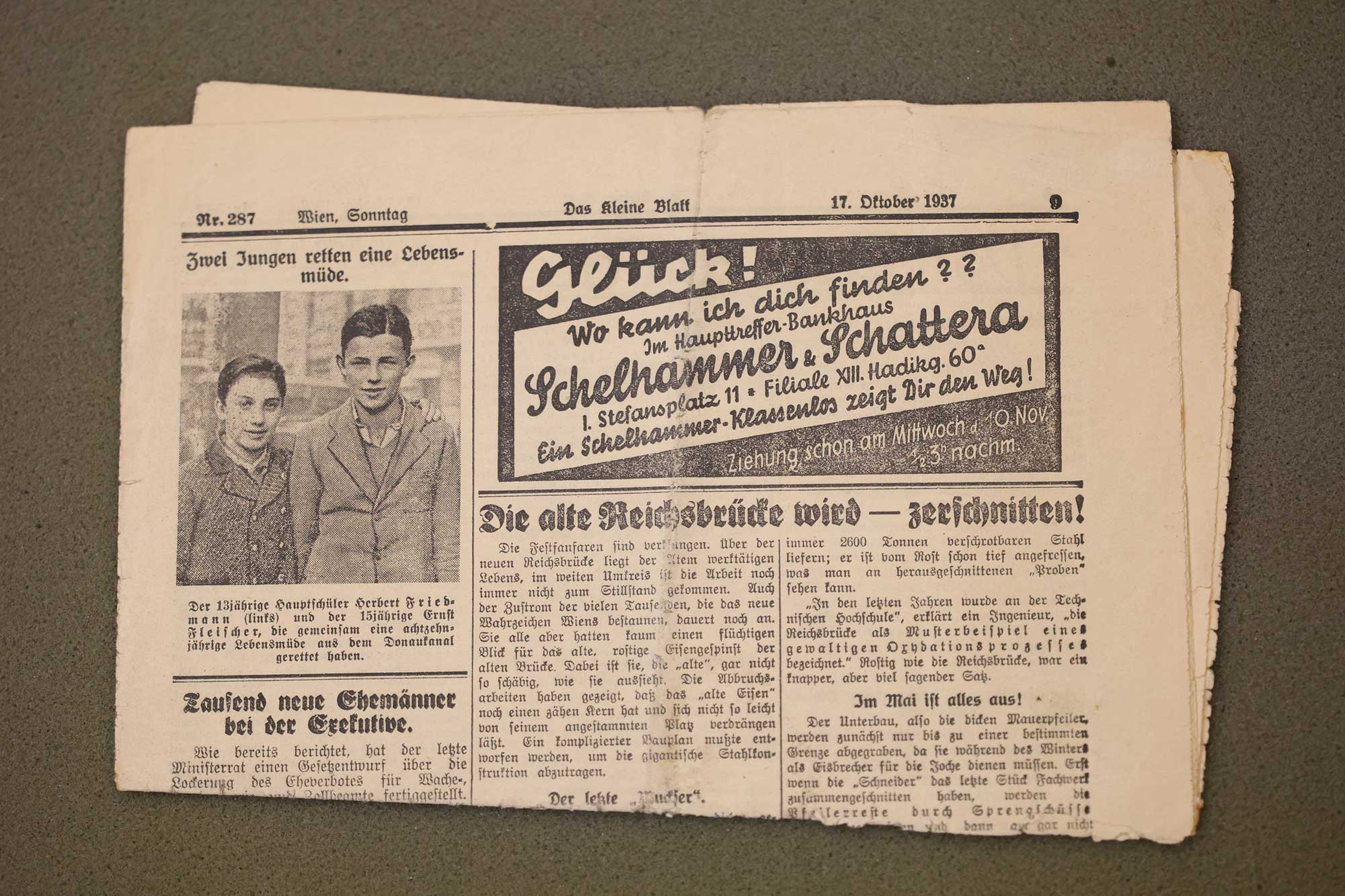

Multiple newspapers document how Friedman and a friend saved a woman from drowning. Friedman carried this newspaper clipping with him from Austria, then England and eventually the United States. (Photo by Matt Riley, University Communications)

The Nazi regime limited what Herbert could bring with him to England, and later, the United States. A packing list, also carefully preserved, shows he brought two sweaters, six pairs of socks and one whole suit of clothes, among a few other approved items, all of which had to be secondhand.

He also brought a clipping from a newspaper telling the story of how he and a friend saved a woman who was attempting to drown herself in the Danube River. “Amidst all the prewar cultural and religious tensions, several newspapers highlighted the youths’ heroism, counterbalancing the villainization of Jews,” head of collection development and curator Krystal Appiah said.

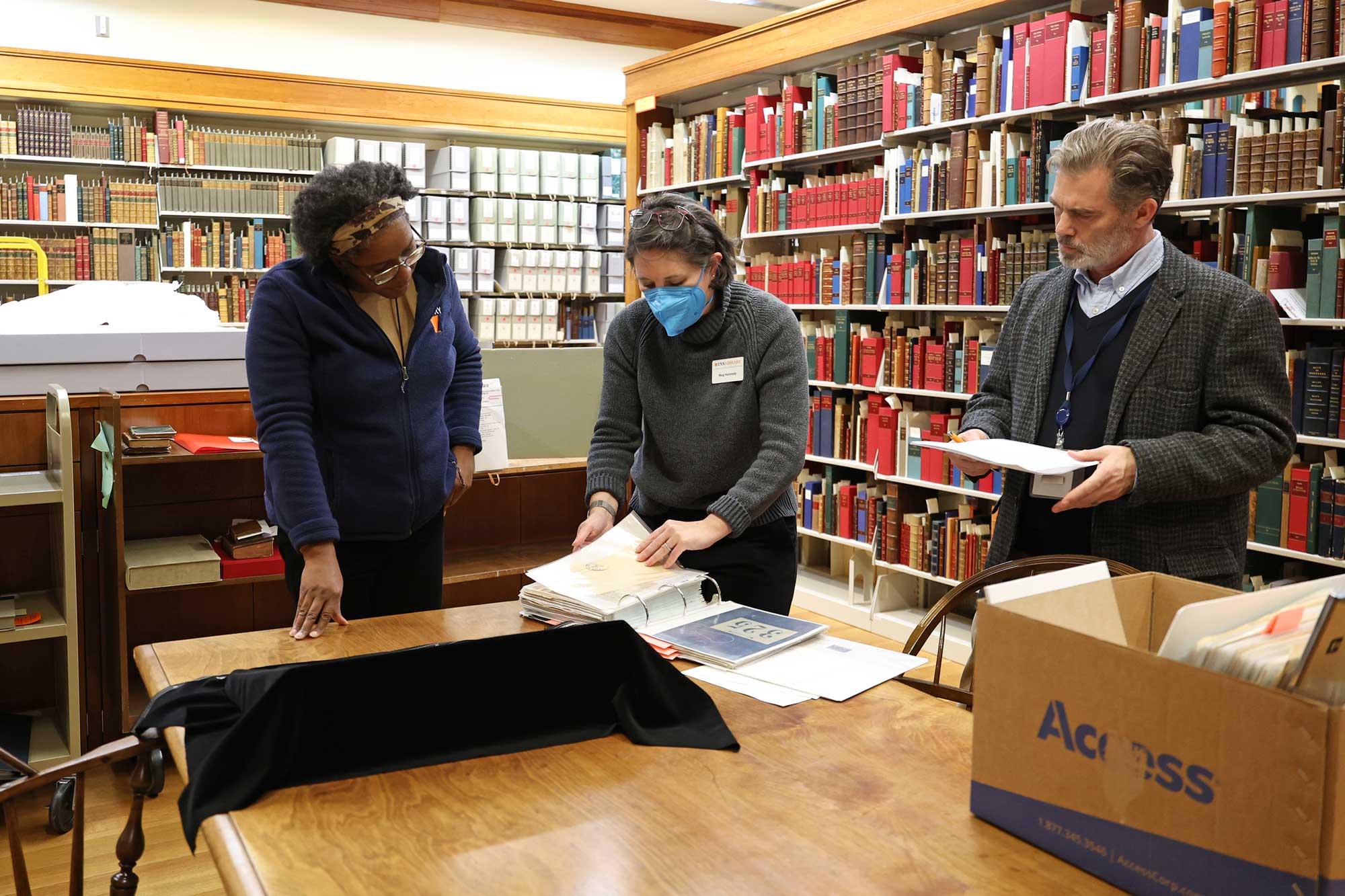

Special Collections curators Krystal Appiah, left, and Meg Kennedy, center, read letters from Friedman’s family in Europe with creative director Jeff Hill. Once the collection is processed, researchers and students will be able to study the materials. (Photo by Matt Riley, University Communications)

Four years after Herbert and his friend, Ernst Fleischer, saved the woman, Fleischer was killed in a death camp in Belarus. Forty years later, the Austrian Embassy in Washington gave Herbert a medal for his heroism.

“Sadly, my friend Ernst was not with me,” Herbert wrote in a short autobiography included in the donated items.

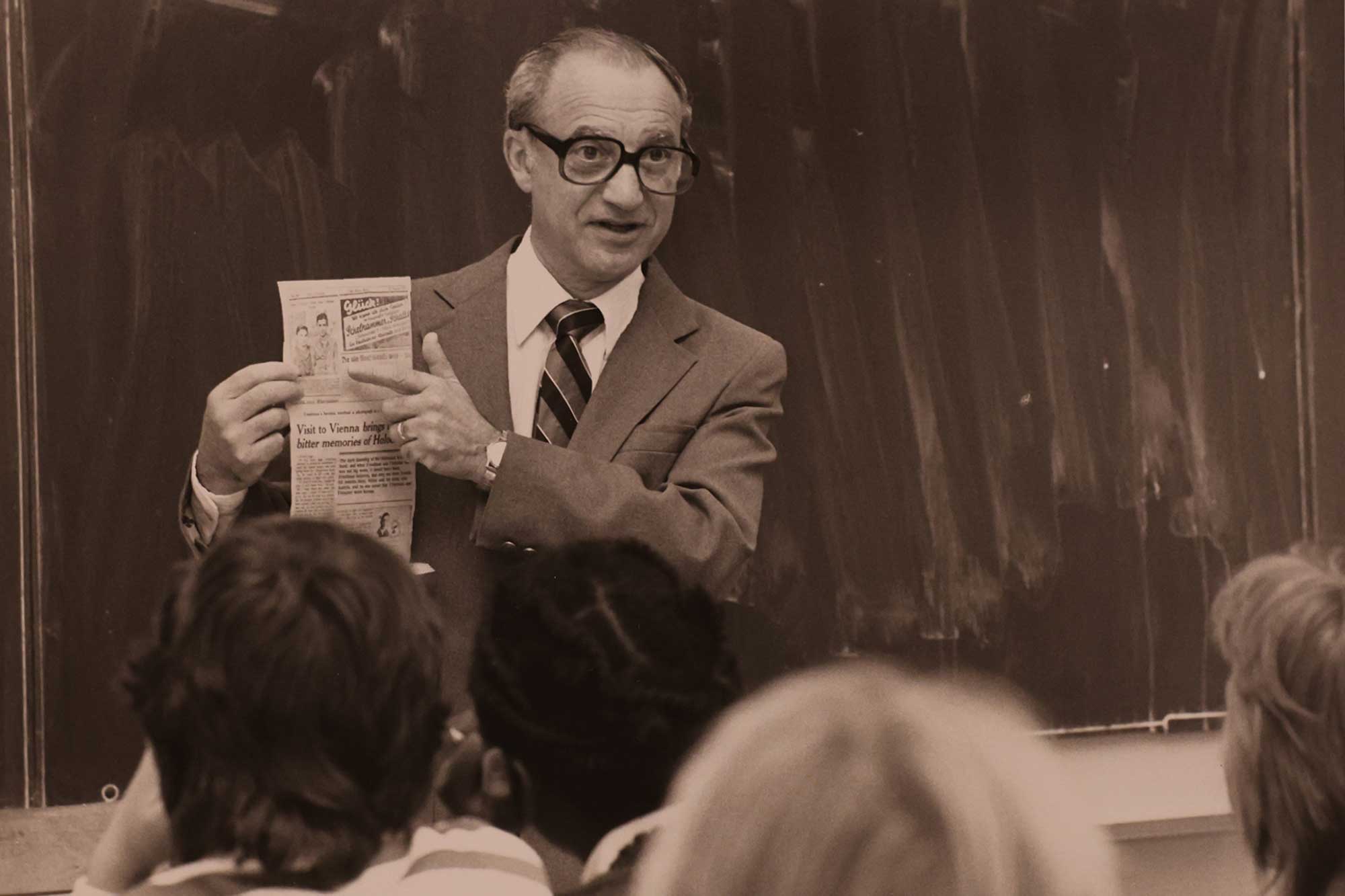

Mark Friedman, Herbert’s son, says his father became increasingly interested in documenting his family history as he aged. Friedman visited schools to teach students about the Holocaust. (Photo by Matt Riley, University Communications)

In 1940, Herbert moved from England to Baltimore. His parents fled Austria in 1939 and joined relatives in Baltimore. Upon graduating high school, Herbert joined the U.S. Army and served in the South Pacific as a medic. When he came home, he attended pharmacy school at the University of Maryland for three years before he was recalled to service for the Korean War.

The Army brought the Friedman family to Norfolk, where Herbert owned a pharmacy. Growing up, Mark was aware of his family’s experience of the Holocaust, but as his father aged, Mark learned more family history.