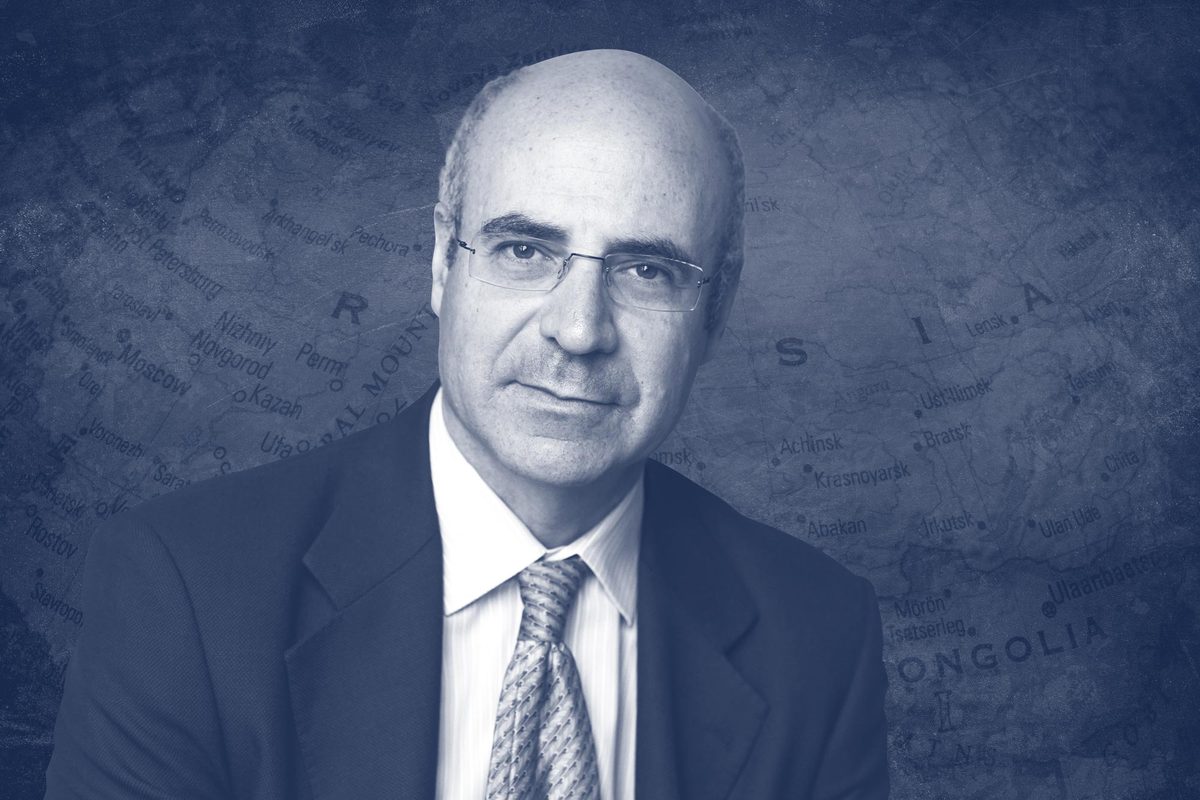

In the early 2000s, William Browder was the largest foreign investor in Russia, taking on some of the country’s most powerful corporations.

Just a few years later, Browder’s company was dismantled on fraudulent charges, he was deported, and his attorney, Sergei Magnitsky, was dead in Russian custody.

Now, Browder – still a wanted man in Russia – is a passionate anti-corruption activist, traveling the world to share his story and promote the Magnitsky Act, a law now passed by the U.S. and several other countries to sanction human rights offenders by freezing their assets and barring entry to the country. His book, “Red Notice: A True Story of High Finance, Murder and One Man’s Fight for Justice,” chronicles his crusade.

On Tuesday, Browder will speak via video chat at an inaugural event hosted by the UVA Democracy Initiative’s Corruption Laboratory for Ethics, Accountability and the Rule of Law, or CLEAR, research initiative. Like other research efforts within the Democracy Initiative, this one will bring the power of academia to bear on the most pressing threats to democracy – in this case, corruption. Faculty members, led by politics professor Daniel Gingerich and economics professor Sandip Sukhtankar, will plan academic courses, research and events exposing the causes, methods and consequences of corruption.

It is a worthwhile mission that, in Browder’s case, comes with plenty of risk. Russian President Vladimir Putin publicly asked for Browder’s extradition in a press conference with President Donald Trump, and Russia has repeatedly charged Browder with various crimes and requested his arrest through Interpol, which rejected the requests as too political.

However, Browder needs only to remember his lawyer to find sufficient motivation.

“I am motivated by justice for Sergei,” he said, noting that Magnitsky was only 37 when he died. “If he had not been my lawyer, he would still be alive.”

Tuesday’s “Corruption and Institutional Decay” event, held at UVA’s Miller Center, is from 10 a.m. to 1:30 p.m. Tickets have sold out but the event will be livestreamed at millercenter.org. More information, including a list of additional speakers, is available here.

We spoke with Browder before Tuesday’s event to learn more about the Magnitsky Act and his fight against corruption in Russia and worldwide.

Q. Your topic on Tuesday is “How Corruption Erodes the Rule of Law.” What are some prime examples?

A. What I learned in Russia is that Vladimir Putin is one of the primary beneficiaries of all the major corruption schemes in Russia. Over the course of his career, he has accumulated a large fortune, which I estimate at around $2 billion.

Most of that fortune is not registered in Putin’s own name, but held by oligarch trustees, which opens up possibilities of blackmail. That fortune is inherently not secure to Putin, because it is held by others. He cannot step down and keep his money, because those people would not necessarily give it back. So he stays in power, breaking rules to make sure that his opposition candidates are killed, imprisoned or exiled, and manipulating elections and the media to control the narrative. I don’t think he will ever step down from power willingly, and I see corruption as the original sin of his dictatorship.

Q. What have you found to be the most effective tools for fighting corruption?

A. Putin’s Achilles heel is that he does not trust keeping his money in Russia; he keeps it in the West. Therefore, Western countries have the ability to freeze, seize and put at risk his entire personal fortune. It is a type of leverage we never had during the Cold War.

That is what makes the Magnitsky Act so effective. It puts dictators’ money at risk, providing real leverage.

Q. Why is it important for universities to study corruption?

A. Universities can help raise awareness. In America, where the levels of corruption are much lower than in places like Russia, people do not appreciate how pernicious corruption is. Often, we don’t have robust enough policies when dealing with these countries because we don’t appreciate the dangers widespread corruption creates.

One of the main dangers is that, in order to stay in power, a dictator often has to deflect the anger of his people. The best way to deflect anger is to start a war with a foreign country. I believe that all of Russia’s military conflicts are rooted in distraction from corruption.

Q. What advice do you have for students hoping to pursue careers in public policy, or otherwise support good government?

A. We are now entering a phase of history where issues of corruption are going to determine the future of the human race. If the corruption gets out of hand, we will end up with conflict, wars and who knows what else. It is one of the most important public issues of our day, and I would advise students, and everyone, to think about how they can contribute in their own way.

Media Contact

Article Information

November 15, 2019

/content/his-fight-against-corruption-had-dire-consequences-russia-now-hes-speaking-uva