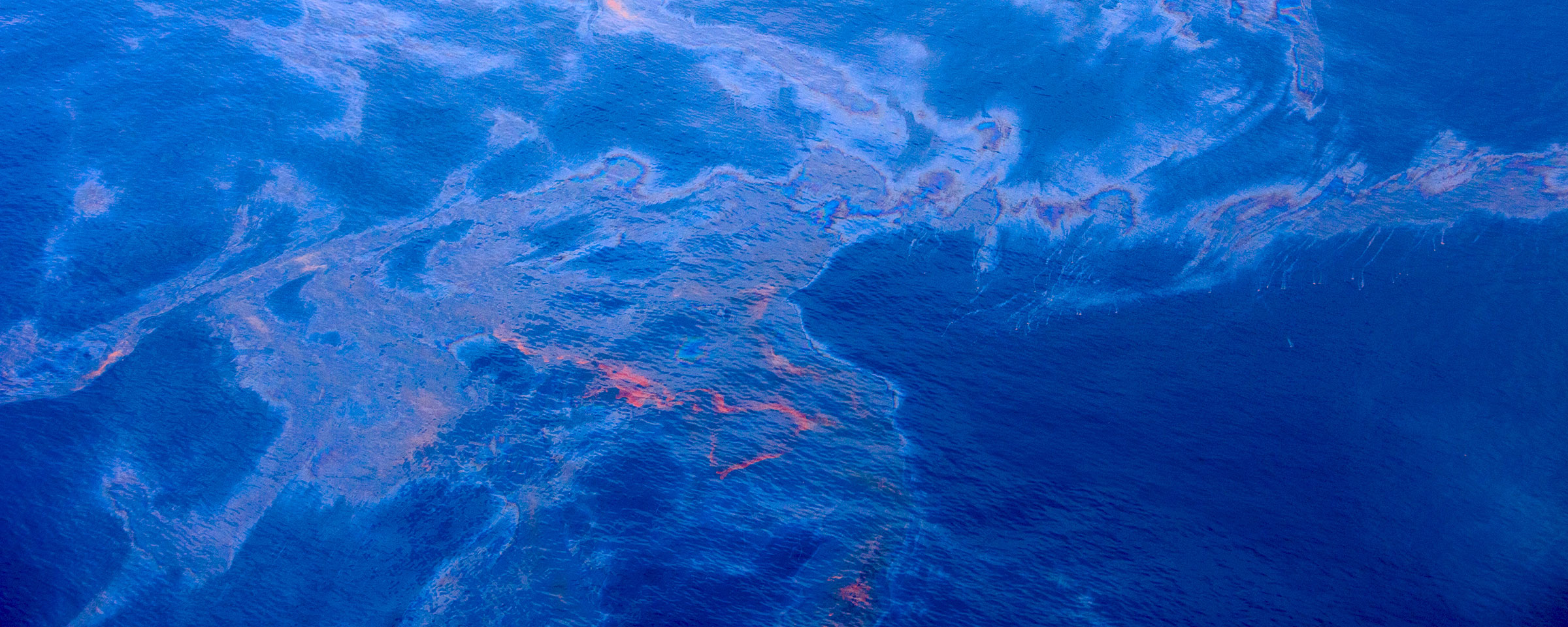

The infamous 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill is the worst offshore spill in United States history, having bled 134 million gallons of oil and gas into the Gulf of Mexico over 87 days. A new Hollywood feature film, opening Friday, tells the story of the devastating accident, which left 11 men dead and dozens injured.

But the devastation didn’t end with the sinking of the burning rig or the plugging of the gusher. It set into motion a crippling environmental crisis that continues to this day.

The spill impacted more than 1,000 miles of shoreline, choked waterways and killed both land and marine life. Scenes of pelicans and sea turtles covered in brown, slick oil filled the airwaves, and Gulf communities decried the ruination of the source of their livelihood.

University of Virginia alumnus Chris Doley is leading the U.S. government’s massive effort to make things right.

Christopher Doley, chief of NOAA’s Habitat Restoration Division, has led the government’s effort to repair the damage from the Deepwater Horizon spill for the last six years.

Assessing the Damage

Doley, who graduated in 1986 with a biology degree (and received an M.B.A. from the University of Texas in 1989), leads the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Habitat Restoration Division. In the five years following the Deepwater Horizon spill, he and his 100-person team assessed the enormous damage and created a restoration plan, a multi-billion-dollar claim presented to British Petroleum, the drilling platform’s lessee.

In April, a judge in New Orleans granted final approval to the estimated $20 billion settlement, green-lighting Doley’s restoration plan.

“That changed the process from the assessment and planning to implementation mode,” he said. “We know what monies we have available, we know what the injuries are and we are now on the task of utilizing those monies in the most appropriate way to restore the natural resources.”

To hash out the settlement, Doley worked with a trustee council that drew from four federal agencies, the Department of Justice and five affected states: Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama and Florida.

“Obviously, the spill impacted local communities and the entirety of the Gulf, so there are lots of people interested – environmental organizations, municipalities, the local governments. They are all very interested in how we will step through and prioritize the restoration necessary. So it is a big job,” Doley said, adding that one goal is to have the process be as transparent as possible.

A Firsthand View

Doley has traveled to the Gulf region nearly every other week for the last six years, and said nothing can compare to seeing the ruin firsthand.

“You don’t have a sense of the expanse of the marshes unless you are out in them,” he said.

Doley was also affected by the passion of the people who live in the Gulf region and how connected they are to the waterways and beaches. He said working the water isn’t “just a job.”

“To people there, it’s their life, and so supporting them in that process is really a major part of the job,” he said.

The BP settlement is uncommon because the money is being recycled right back to the Gulf, Doley said. “In some cases, the money goes back to the treasury, or other places. In this case, we’ve been working very closely to really focus any recoveries we have back into the Gulf,” he said. “The piece that I’m particularly responsible for is the natural resource damage assessment under the Oil Pollution Act. There is about $8.8 billion associated with that part of the settlement.”

A Massive Undertaking

The restoration of the Gulf region is projected to continue for the next 15 to 20 years. There are already nearly 90 projects spread across the affected states and out into the Gulf itself.

About 3½ years ago, Doley’s group got a jump start on restoring the region when they negotiated with BP for an early payout of $1 billion to begin what Doley called “early restoration.” That work has included beach repair and public access projects.

In Texas, work is ranging from a $45 million sea turtle restoration project to nearly $2 million to create an artificial reef by sinking a ship to enhance recreational fishing and diving opportunities.

In Louisiana, $320 million is going to the restoration of beach, dune and back-barrier marsh habitats at four barrier island locations. “These islands are essential to the resiliency of coastal Louisiana,” Doley said.

In Alabama, more than $11 million will restore about 50 acres of salt marsh, a habitat for species like turtles, fiddler crabs and snakes.

Along the shores of Mississippi, $50 million will be used to create a living shoreline, marsh and subtidal oyster reef.

Doley said some of the restoration work is extremely difficult. “When you injure a population of dolphins, you can’t just plant more dolphins like you might be able to do marsh grass,” he said. “Some of these are very difficult and untried types of techniques. So we have scientific teams working to try to figure out what is best to do to restore the dolphin population.”

Life at UVA

Doley said his UVA education has played an instrumental role in his work.

“My job is half-technical and half-management,” he said. “You’ve got to understand the technical issues, like how to rebuild a marsh or assess how oil can impact the environment as well as managing public engagement and large-scale construction projects.

“The foundation that I received in science from UVA has served me well in my career,” he said.

Doley said he looks back fondly on his years in Charlottesville. “I had three really close housemates and we lived behind the fraternity area,” he said. “I had a girlfriend that I ended up marrying, my first-year sweetheart who I met in Tuttle [House residence hall].

“I had a pretty typical experience, working in class, but also enjoying UVA. There is no place like UVA,” he said.

Doley and his wife come back to visit Charlottesville with their four children from time to time.

“The place I enjoy coming back to the most is the Lawn, obviously,” he said. “It’s just the most nostalgic and it’s where you really feel the history. It’s hard not to go back to the center, the heart of the University.”

Media Contact

Article Information

September 29, 2016

/content/hollywood-film-premieres-alumnus-leads-gulf-restoration-efforts