Robert Mueller, the understated, square-jawed former Marine, has built a professional reputation that is beyond reproach – first as a prosecutor, then later as the FBI director who reinvented the bureau after the Sept. 11 terror attacks.

He is devoutly nonpartisan. That neutrality allows him to be a better public servant, he has said.

His colleagues describe him as calm, thorough and focused.

In May, the deputy attorney general of the U.S. Department of Justice named Mueller, a 1973 UVA Law School graduate, special counsel in the inquiry whose central question has hounded the current administration: To what extent, if any, did President Donald J. Trump and his advisers collude with Russia to try to tip the balance of the election in their favor?

The answer could take months to explore, if not years.

No matter what the investigation might find, the 73-year-old Mueller is expected to conduct the probe as he has always gone about his work: conscientiously. “I accept this responsibility and will discharge it to the best of my ability,” he announced upon resigning from his law firm, WilmerHale.

Professor and former UVA Law Dean John C. Jeffries, a member of Mueller’s law class, said no better person could have been selected for the job.

“Robert Mueller is the perfect choice,” Jeffries said. “Most important is his integrity. For Bob, integrity is not merely a policy or a practice; it’s character. He is incapable of dishonesty or dissembling. Additionally, he has the skill and experience to be effective. His appointment has been universally applauded, as it should be.”

‘Never Took His Eyes Off His Mission’

Despite having every reason to be a widely recognized public figure on par with J. Edgar Hoover, the only director to have led the FBI longer, Mueller managed to keep a relatively low profile. Perhaps this was best exemplified by the “Who is Robert Mueller?” articles that surfaced after he was announced to lead the investigation.

Who is Mueller? He is one of the key players who strived to make the nation safer after Sept. 11.

Mueller converted the FBI from a mostly after-the-fact, crime-solving organization to one focused on threat prevention. With his counterterrorism mandate, Mueller oversaw a reorganization of the bureau that involved the retraining of existing agents and the massive hiring of new ones – all the while improving coordination with outside law enforcement agencies and the intelligence community.

Robert Mueller speaking at the University of Virginia School of Law (Photo by Cole Geddy, University Communications)

He was appointed to lead the bureau a week before the attacks happened. Due to his effectiveness at the job and President Barack Obama’s need for continuity, Congress authorized him to serve two years beyond the job’s modern 10-year term limit.

One of Mueller’s financial advisers told him he was hurting himself by staying on, rather than pursuing more lucrative opportunities, according to Princeton University classmate Robert Nahas.

Mueller’s response, Nahas said, was, “When the president asks …”

“Like the Marine that he’s always been, Bob never took his eyes off his mission,” Obama said in 2013 during a ceremony thanking Mueller and welcoming his successor, incoming director James Comey.

The Firing Memo and ‘Related Matters’

Comey, of course, is the man Trump appeared to have fired for looking into, according to the president’s words, “the Russia thing.”

A May 8 memo that came from Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein, however, took a different tack as justification for firing Comey. Instead of addressing Trump and Russia, it blamed Comey’s handling of an investigation into former presidential candidate Hillary Clinton’s use of a personal email server while secretary of state.

Then, in a dramatic turn – and with Attorney General Jeff Sessions having recused himself from all matters related to the Russia investigation – Rosenstein appointed Mueller as special counsel on May 17.

Per federal law, the power to appoint special counsel occurs when conflicts of interest “or other extraordinary circumstances” prevent the U.S. Attorney’s Office or litigating division of the Department of Justice from prosecuting a case and “under the circumstances, it would be in the public interest” to appoint counsel.

Democrats and Republicans alike were supportive of Mueller’s selection for the job. Then-House Oversight and Government Reform Committee Chairman Jason Chaffetz, a Republican from Utah, tweeted, “Mueller is a great selection. Impeccable credentials. Should be widely accepted.”

U.S. Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse, a 1982 UVA Law grad, Democrat from Rhode Island and a member of the Senate Judiciary Committee, has been a leader in the Senate’s probe of election tampering.

“Russian interference in our election and the troubling actions of this White House demand the fullest accounting of the truth,” the senator said in a statement. “Mr. Mueller has been granted authority to pursue whatever he deems ‘related matters.’”

Until the investigation is complete, an overarching question will remain: What level of collusion would rise to impeachability?

“Impeachment is partly a perception question,” Professor Saikrishna Prakash told Newsweek. “Imagine Trump [has] had several conversations with Vladimir Putin about how to harm Hillary Clinton’s prospects. There will be plenty of people who think it’s an impeachable offense, and others who would say it’s terrible, bad judgement, but doesn’t rise to their level of what an impeachable offense is.”

A Defining Moment: The Ashcroft Incident

With a straight-laced persona recognized by both sides of the aisle, Mueller seems to have been chosen as much for his character as to do the work.

Mueller was a President George W. Bush appointee to the FBI who earned the Republican’s respect, even though he would stand up to his administration over concerns it was violating constitutional rights.

The story of the principled standoff against White House Counsel Alberto R. Gonzales and Bush’s chief of staff, Andrew H. Card Jr., has become the stuff of legend.

On March 10, 2004, Gonzales and Card asked Attorney General John Ashcroft, who was suffering from a pancreatic ailment and in the intensive-care unit at George Washington University Hospital, to sign papers that would reauthorize the administration’s “Stellar Wind” domestic surveillance program. The men had not resolved legal conflicts over privacy that concerned both the FBI and the Attorney General’s Office.

Comey was Ashcroft’s deputy at the time and believed himself to be acting in Ashcroft’s stead due to the incapacitating illness. After Comey caught word of the scheme to circumvent his authority, he alerted Mueller, and both men rushed to the hospital.

Mueller instructed his agents by phone to make sure Comey, who would get there first, wasn’t removed from the room by the Secret Service.

The tense showdown was ultimately diffused by Ashcroft himself. He summoned enough lucidity to reject the reauthorization – and even state his reasons why – before losing his bearings again.

Despite the incident, the Bush team pressed forward to reauthorize. Mueller – along with Ashcroft, Comey and their aides – tendered their resignations over the matter in a stunning no-confidence vote.

Mueller and the others never publicly stepped down, however, because the president “blinked,” according to journalist Garrett Graff, who wrote about the incident in his book “The Threat Matrix: The FBI at War in the Age of Global Terror.” (The exact details of their policy compromise have not been revealed; Bush has since stated he was merely looking for his best legal footing for the surveillance program.)

For Graff, who has interviewed Mueller more than any other journalist, Mueller wasn’t just a great choice for the job; he may have been the only choice.

“Because of the deep respect and reputation Bob Mueller has in Washington, the good news for President Trump is if there is no ‘there’ there, if this is all a strange case of odd coincidences and misunderstandings, Bob might be the only person in America who could come out, declare Donald Trump and his associates innocent, and be believed by both parties,” Graff said in a recent C-SPAN interview.

A Prosecutor at Heart

At the core of his being, Mueller wants to pursue justice wherever it leads.

“In his heart of hearts, he’s a prosecutor,” the late Lee Rawls, Mueller’s former chief of staff and a classmate at Princeton, was once quoted as saying.

Before taking the helm at the FBI, Mueller rose to become assistant to the attorney general in 1989, then head of the Justice Department’s criminal division in 1990. He oversaw investigations into the terrorist attack on Pan Am Flight 103 and the criminal activities of Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega and crime boss John Gotti.

After he left Justice, following a brief stint as a law firm partner, he took what many would consider a step backward in his career. In 1995, he went to work for the U.S. Attorney’s Office in D.C. as a litigator in the homicide section.

To Mueller, though, the choice was about filling a public service need. The district had a rampant crime problem. Something had to be done.

“Doing homicides, the victim’s family was always present in your mind,” he told UVA Lawyer in a 2002 interview. “You’re trying to find and bring justice to them.”

He added, “Working as an assistant U.S. attorney, I’ve seen how people think that they can get away with things and skirt the law. Bringing them to justice is tremendous satisfaction.”

A Man of Oaths, Pledges and Mottos: UVA Law Experience Formative for Mueller

Robert Swan Mueller III is a man of oaths, pledges and mottos for whom personal integrity is paramount. His reputation is the currency on which he trades, and it means everything to him.

“We’re only as good as our word,” Mueller told the Law School community when he accepted the 2013 Thomas Jefferson Foundation Medal in Law, shortly before exiting the FBI. “We can be smart, aggressive, articulate, perhaps persuasive. But if we’re not honest, our reputations will suffer. And once lost, a good reputation can never, ever be regained.”

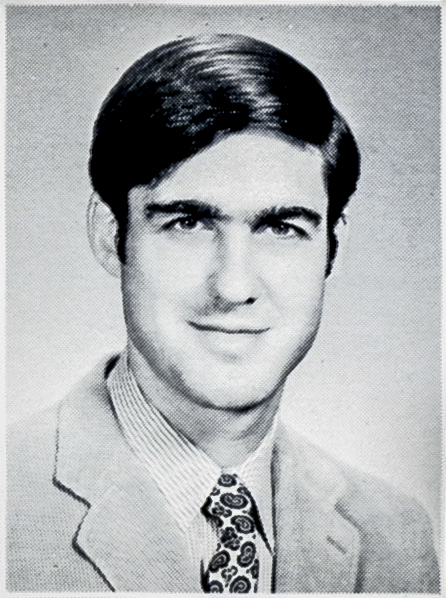

Robert Mueller’s 1973 UVA Law School yearbook photo (Photo courtesy of UVA Law Library)

Born in New York City and raised outside of Philadelphia, Mueller was the only boy among five siblings. His father was a DuPont career man and former Navy captain who led a sub-chaser during World War II. Mueller attended Princeton University, where his father had gone. He earned a bachelor’s degree in political science there in 1966 and a master’s in international relations from New York University in 1967.

How Mueller became the professional he is today is a broad story, but one tied in large part to his training at UVA Law, which he has called “one of the best, if not the best, law schools in the country.”

“Then as now, UVA was different from other law schools in rather than simply teaching the basic tenets of the law, it sought to provide the foundation for future leadership,” Mueller said in his Jefferson Medal remarks.

Mueller chose to attend UVA because the school was welcoming to veterans, whose leadership skills the school prized. Mueller decided to take the Marine Corps oath after he learned a friend had died in Vietnam. He served as second lieutenant leading a rifle platoon of the 3rd Division in Quang Tri Province and became a general’s aide. He earned several combat decorations. During a mission to rescue American soldiers hemmed in by a firefight in 1969, he was wounded by an AK-47 round to the thigh, earning him a Purple Heart.

“He had a distinguished time in the Marines, was combat-decorated and a real leader, but he spoke little about that period,” Law School classmate Marschall Smith said. “He saw UVA as a chance to build a career supporting the rule of law and building solid institutions.”

Mueller attended law classes with a number of fellow ex-Marines and other former service members. (Today, the Law School continues to welcome veterans. Representatives from all the branches of the military are members of this year’s incoming class.)

Mueller also was drawn to UVA for its honor code. Students pledge not to lie, cheat or steal, under the penalty of expulsion.

“Nothing sets Virginia apart from other universities more than the concept of honor,” Mueller said in his 2013 speech. “The Honor System, in place since 1842, and the community of trust it enables, rests on one precept – and that is integrity. Our careers in the law, our professional and our personal success – and indeed, our reputations – rest on that same precept.”

Mueller worked hard at UVA, and was involved in activities outside of his classes. In his first year, he was a section representative to the Law School Council. In his second year, he tested onto the Virginia Law Review, acing a writing and editing exercise that only eight others passed. He also served as a research assistant to then-UVA Law professor Mason Willrich, who had been assistant general counsel for the U.S. Arms Control and Disarmament Agency during the Kennedy administration.

“Bob Mueller was my favorite law student, who has been a good friend ever since,” Willrich said. “You could tell that he was really mature and that he was really anchored in good principles. He was also just a dynamic type of a person and with leadership skills that are rare. We socialized a lot and it was a pleasure to be with him. Clearly he was very public-minded even then.”

Mueller’s classmates were also impressed with him. “I recall Bob as a very serious law student,” Smith said. “My sense was he never came to class unprepared. He avoided politics and emotionalism in analyzing cases, doing thorough research, applying precedent in a thoughtful and disciplined way. The superb faculty at the Law School were men and women he greatly respected.”

Cameron Smith, who was also a member of the Class of 1973 and unrelated to Marschall, said in addition to his Law School commitments, Mueller played squash two or three times a week with him and others, including Willrich and law professor Ted White. They played hardball singles at what used to be the Albemarle Racquet Club.

Mueller seldom lost. “I don’t think he ever slacked off at anything,” Smith said.

As a student, Mueller drew inspiration from an inscription over an archway on Grounds, attributed to former UVA President Edwin Alderman: “Enter by this gateway and seek the way of honor, the light of truth, and the will to work for men.”

Mueller started his career at the law firm Pillsbury, Madison and Sutro in San Francisco, but he wasn’t there long before taking the Justice Department oath and starting his career as a prosecutor.

He would later be appointed to lead the FBI, in 2001.

“Our motto at the bureau is ‘fidelity, bravery and integrity,’ and uncompromising integrity, both personal and institutional, is the core value,” Mueller told law students in his 2013 medal talk. “For attorneys and not-attorneys alike, there will come a time when you will be tested in both ways small and large,” he said. “You may find yourself standing alone against those who you thought were your trusted colleagues. You may stand to lose what you have worked for, and the decision will not necessarily be an easy call. But this institution, Virginia, has prepared its students for such tests, for integrity is a way of life here at this institution.”

Media Contact

Article Information

November 9, 2017

/content/honor-and-integrity-make-73-law-grad-robert-mueller-right-election-inquiry