This is a fruit fly.

This is a fruit fly on drugs.

Any questions?

OK, you probably have at least two: First, why would anyone give a fruit fly drugs? And, as a follow up, how would you know if the drugs were working?

Illustration by Emily Faith Morgan, University Communications

This is a fruit fly.

This is a fruit fly on drugs.

Any questions?

OK, you probably have at least two: First, why would anyone give a fruit fly drugs? And, as a follow up, how would you know if the drugs were working?

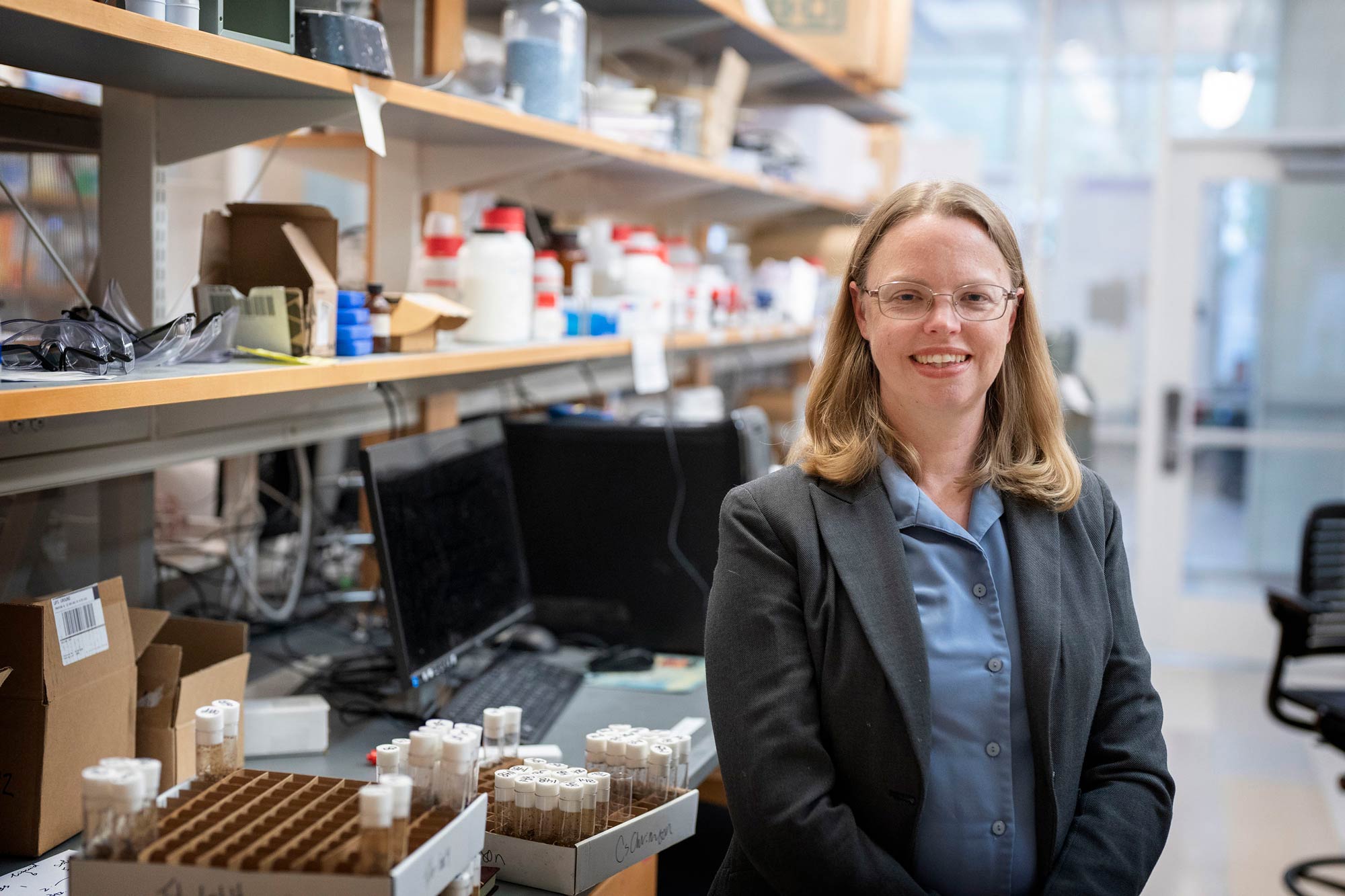

The answers to questions like these can be found in Jill Venton’s lab at University of Virginia. She chairs the Department of Chemistry and is an expert in the juices that get brains flowing.

Ten years ago, her group was the first to insert tiny sensors into fruit fly brains to track the work of individual chemical molecules. Now, the research she oversees is illuminating how certain drugs might work to fight depression in the darkness of the human brain.

Among other molecules, the lab has begun studying the path of serotonin. The chemical is an important messenger within the brain and throughout the body. Vital functions such as mood, sleep and appetite (both for food and amore) are thought to rely heavily on our ability to self-regulate the stuff.

Jill Venton, who has spent the entirety of her accomplished academic career at UVA, chairs the Chemistry Department and heads her own lab. (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

When our brains don’t seem to be able, doctors often turn to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or SSRIs. The drugs go by brand names such as Prozac and Lexapro, and they’re most often prescribed for anxiety and depression.

“The protein in the brain that the SSRI works on is called ‘the serotonin transporter,’” Venton said. “The transporter’s basic job is to take serotonin back up into the nerve cell. The way the SSRI works is, it says, ‘Don’t clear the serotonin anymore. Let it stay out there.’ Because when it’s out there in the brain, it can do more signaling.”

Upward of 13% of the adult population, or more than 30 million Americans, take SSRIs.

“There’s a lot of controversy right now in the field over serotonin,” Venton said. “For years, we’ve been giving these drugs that attack the serotonin system in hopes that they raise your levels. But is the serotonin level really low in depressed patients? We don’t know, and we don’t have a really good way to measure that for a human.”

In the search for answers, enter the once pesky fruit fly.

From Venton’s perspective, there’s much to larvae – err, love – about Drosophila melanogaster, the common fruit fly.

“Believe it or not, the fruit fly brain and the human brain have a lot of similarity,” she said.

Originating from only four pairs of chromosomes (versus 23 in humans), the brains of these invertebrates are far removed from our own processing capacity. Yet about 75% of the fly’s genes are the same as ours, and their chemical pathways largely duplicate.

The result is a research model that’s both simple to study and highly useful for making predictions about humans.

Drosophila melanogaster has had a long history in scientific experiments since Thomas Hunt Morgan first won the Nobel Prize in 1923 for demonstrating how parents pass along traits to their offspring. Fruit flies have the benefit, for researchers at least, of living relatively short lives, while reproducing quickly and plentifully. That means experiments can be performed in rapid variation. Scientists can form reliable conclusions over a matter of weeks, rather than months or years.

Venton knew that neuroscience could also benefit from what flies can tell us – if scientists could find a way in.

“We’re chemists, but we work in neuroscience, so that automatically makes us just a little bit weird, but exciting, too,” she said. “Our lab develops these tiny little electrochemical sensors, and our purpose in putting them in the brain is to understand basic mechanisms of how the brain works and how it goes wrong during disease.”

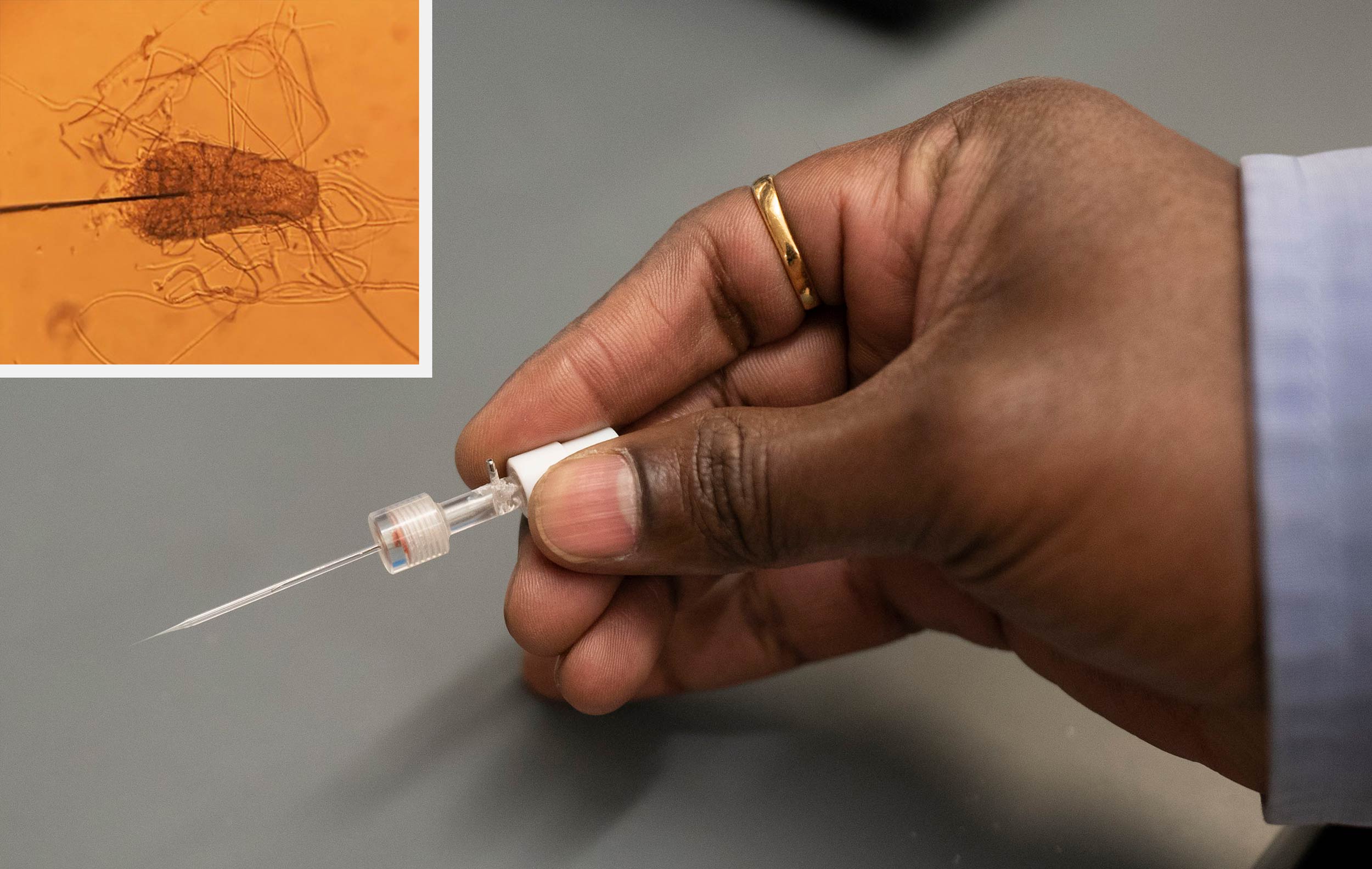

The first measurements were made here in collaboration with UVA biologists Jay Hirsh and Barry Condron.

These days, however, the University partners with Oak Ridge National Laboratories to laser-print the polymerized sensors to the exact size and shape needed. At about 7 microns in diameter, the tip is small – smaller than a human hair. The electrode is super-heated after fabrication, forming carbon fiber that allows the sensors to conduct electricity.

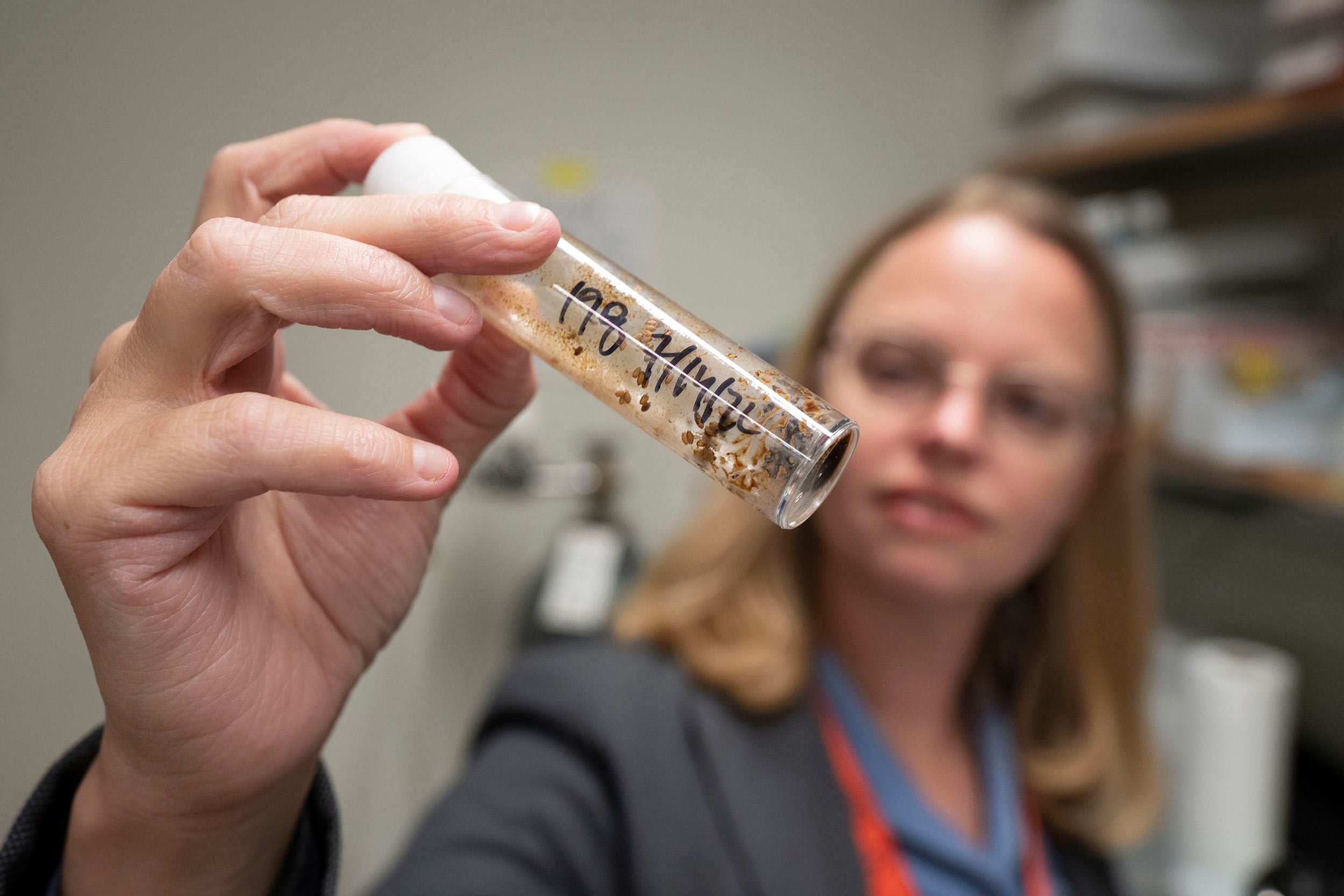

Meanwhile, UVA researchers breed the fruit flies in Venton’s lab.

They use what’s called “optogenetics,” a technology that can make certain neurochemicals, such as serotonin, transmit when exposed to red light. The light activates a yeast-associated protein in the fly.

That helps the postdoctoral researchers and graduate students (and, in some cases, advanced undergraduates who may be assisting) put the electrode in the right place.

But first, they have to remove the ventral nerve cord of the fly – often in larvae form – to gain access to the neuron-specific tissue. The surgery is performed under a high-powered microscope.

In preparation for studies, the researchers typically feed the flies the drug being studied by adding droplets to their food.

Once the studies are underway, the researchers stimulate the drug-affected neurons by introducing electrical charge to the probe, which is encapsulated in a glass sheath for insulation. Fast-scanning equipment then translates the changes in voltage and current into useful graphs.

Over time, the lab has explored everything from the role of dopamine in fly-simulated Parkinson’s disease to how adenosine may be helpful during a stroke.

“We are still about the only people who know how to put these sensors into a fruit fly brain,” Venton said. “I think most people would have thought it was impossible to take a fruit fly and make any measurement.

“Recently, we took flies that were still alive and awake, and we looked at their dopamine levels as we fed them sugar. Even I’m impressed we could do that.”

How do you make fruit flies depressed? You could tell them they only have six to 15 days to live … or you could, like Jefferson Fellow and doctoral student Kelly Dunham did, alter their feeding habits and monitor how they move.

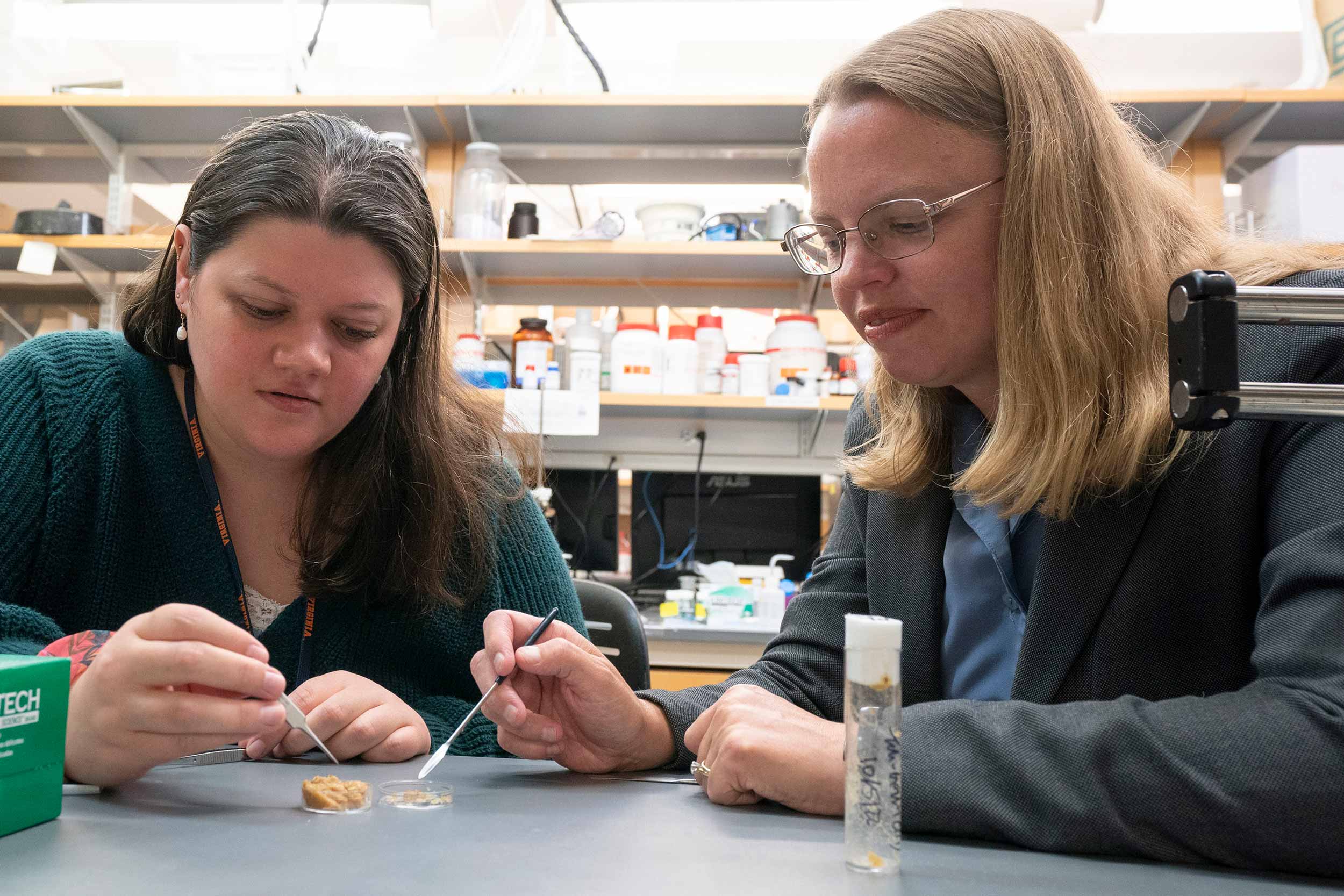

That’s how Dunham prepped her larvae specimens for the lab’s recent, first-of-its-kind SSRI study. She was the lead author of the research, published with Venton this summer in the Journal of Neurochemistry.

In particular, the study looked at the reuptake and release characteristics of four popularly used SSRIs.

“Though they’re a collective group called SSRIs, they all have different mechanisms of action,” she noted.

Regardless, one of two things are probably going on overall: “For depressed patients, the biggest thing doctors think is either the serotonin is going through reuptake too quickly, and it’s not staying in the brain, or there’s just too low of levels,” Dunham said.

So which SSRI did the best job of addressing these issues?

Two drugs, escitalopram and citalopram, both increased the release of serotonin and slowed reuptake.

But those results come with some nuance, Dunham and Venton said – prohibiting any of the drugs from being declared the clear “winner.”

From the public’s perspective, it might appear that SSRIs all act in roughly the same way. But that’s not what Dunham and Venton observed.

Escitalopram, better known by the trade name Lexapro, and paroxetine, better known by the brand name Paxil, increased the brain’s serotonin concentrations at all doses, yet apparently did so much differently.

“Paxil has a faster reuptake compared to Lexapro,” Dunham said. “Paxil binds to the serotonin transmitter with really high affinity, and the concentrations were huge. We think there’s a different molecular mechanism for how it works compared to Lexapro.”

In contrast to these two drugs, citalopram (Celexa) showed relatively lower serotonin concentration increases during the study, despite also slowing reuptake.

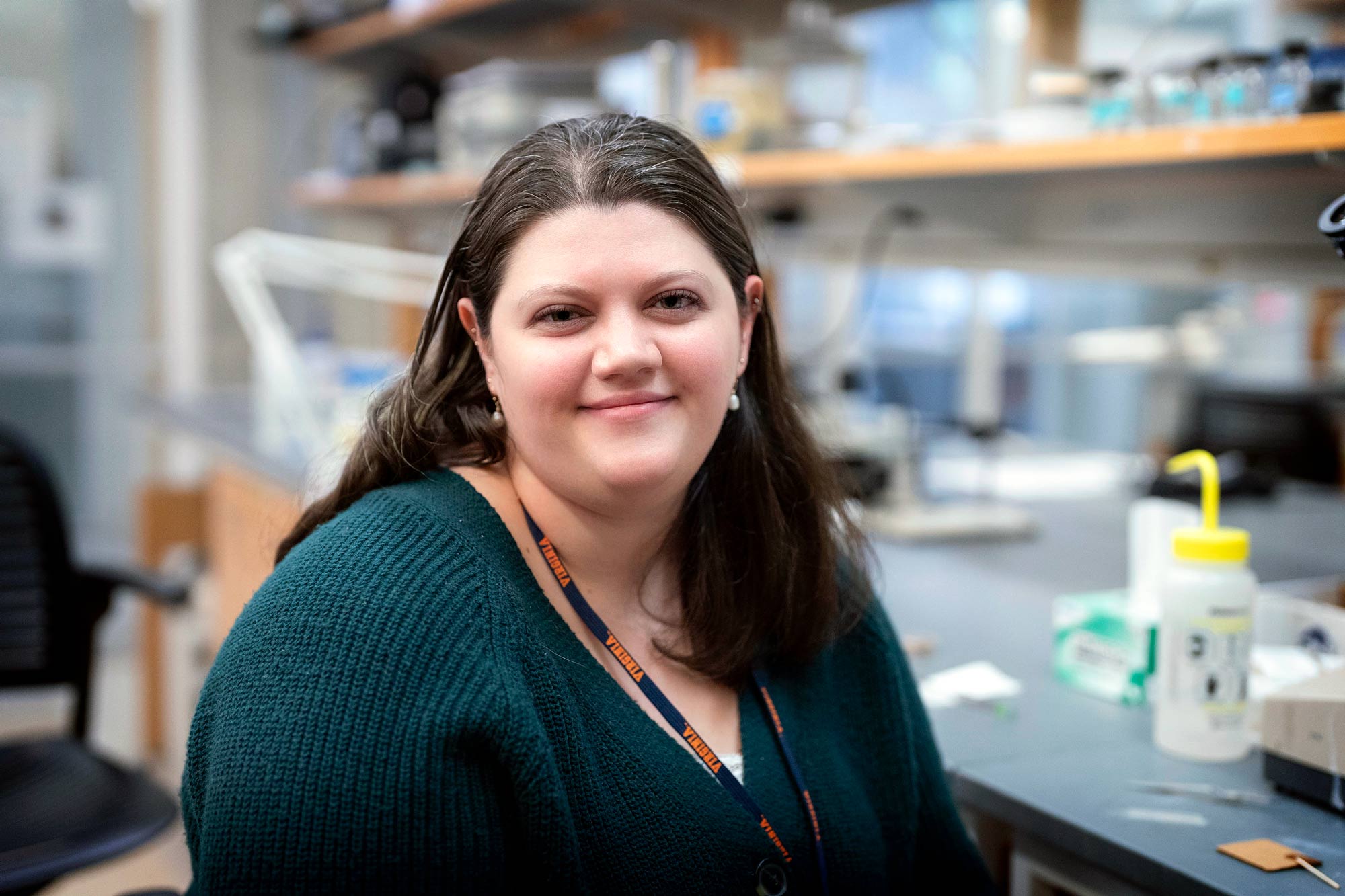

Kelly Dunham is currently working on serotonin detection and measurement. She hopes to apply her work to pharmacology. (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

Finally, the first-ever SSRI approved in the U.S., fluoxetine (Prozac), did not increase concentrations of serotonin, at least during the limited duration of the study.

“We think Prozac has more of an effect just on reuptake,” Dunham said. “It might be one you have to take it over long periods of time to change the brain chemistry.”

Based on this study alone, she said, it’s not possible to rank the desirability of the drugs. People’s genetics and individual conditions differ. They experience differing levels of improvement on the drugs and, in some cases, suffer differing side effects.

More research is needed, but it’s a start.

Subsequent students in Venton’s lab will test SSRIs against mutations of the serotonin transporter that Dunham and Venton hope will effectively mimic some of the basic genetic variations of humans.

Dunham said the mechanisms of how these and other antidepressant drugs work matter because current prescribing can be hit or miss.

The goal, of course, is to move toward matching each unique patient with the most safe and effective pharmaceutical.

“I hope this research starts a conversation on antidepressant treatments,” she said. “The most common thing is doctors prescribe a drug, and there’s no way to understand what they think works best for the patient. The patient may have to try two or three drugs to find out.”

Dunham is a Cookeville, Tennessee, native who performed her undergraduate study at Tennessee Tech University. She is currently investigating the effects of ketamine on fruit flies. The psychedelic alternate to SSRIs is thought to help people with treatment-resistant depression – often in one dose, rather than in continuing doses over long periods of time.

She said that among her non-scientist friends, she has heard many a joking reference to the horror film “The Fly.”

Though she will be graduating UVA in the spring, Dunham will continue on at the University. She will serve as a postdoctoral researcher next year and teach an undergraduate course about empirical research and the history of antidepressants as part of the new Engagements curriculum. An influence for the course was a UVA sociology course, “Prozac Culture,” taught by Joseph Davis.

Dunham is just one of the lab’s many success stories. The students who work for Venton often move on to successful careers in academia and private industry.

Leah Weizman, an undergraduate who performs dissections and assists with other work in Venton’s lab, lined up summer work at two pharmaceutical companies. (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

A third-year undergraduate student, Leah Weizman of Reston, worked a previous summer at Merck and has lined up a project with Eli Lilly for next summer due, in part, to experience she has gained in the lab.

As to her own path, Venton has spent the entirety of her career at UVA, which fostered her development as the type of chemist she wanted to be, she said. Her mission is to continue that, by serving as a resource for students as they pursue their own discoveries.

“I chose UVA as an assistant professor because they were willing to allow me as a chemist to do interdisciplinary research,” she said. “Man, I love research. And the best part of my job by far is working with students in my research lab. To see them develop personally and professionally is really fulfilling.”

For Venton, who was recognized in an October ceremony with the 2022 Advances in Measurement Science Lectureship Award, an international honor which few scientists receive, the future of fly research doesn’t stop with just one sensor.

“The brain puts out a concoction of molecules, and we do not currently know how to study multianalytes,” she said. “In the next five or 10 years, I’m going to shift my lab to do multiple things at a time. That will require new tools and a new direction. We will track one or two molecules with a sensor, and one or two with microscopy and light.”

Last year, Venton helped UVA claim four National Institutes of Health grants, representing $12 million in current or upcoming lab research. Two of the grants involve the new direction she’s headed.

“When we get there,” she said, “I think we’re going to find certain drugs like SSRIs are affecting way more than we ever knew. Then the drug companies are going to get really interested.”