The story in the Washington Post recounted the experience of a 47-year-old Russian employee of an ice skating rink in a village in the Rostov Oblast region near Russia’s border with Ukraine.

Moved by Vladimir Putin’s decision to attack Ukraine, the man “wrote an anguished social media post, lamenting the ‘horror and shame’ of a war that ‘will be catastrophic,’” according to the article written by the Post’s Moscow bureau chief, Robyn Dixon.

The next day, police with weapons showed up at the man’s home, arrested him and charged him with “showing disrespect for society and the Russian Federation,” Dixon reported.

In the United States, such an action goes against the grain of fundamental beliefs and principles. But as the democratic nations of the world galvanize to oppose Russia’s assault in the Ukraine, anecdotes such as this one help remind us what’s at stake when leaders discuss the escalating threats to democracy.

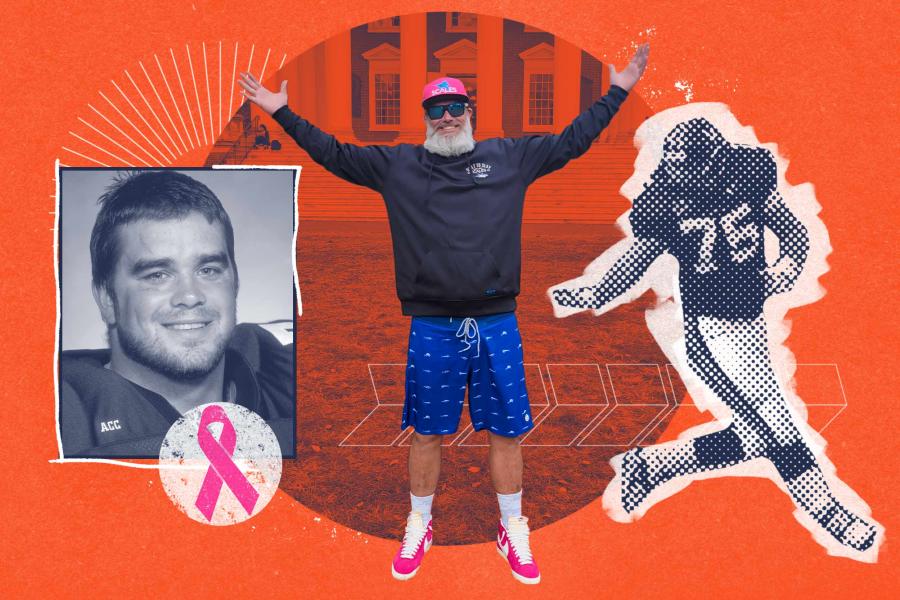

UVA Today checked in with John M. Owen, the Taylor Professor of Politics, to gain perspective and context on the larger struggles around democracy that Russia’s unprovoked war against Ukraine symbolizes. Owen also is a senior fellow at the Miller Center and a senior fellow at the Institute for Advanced Studies in Culture.

John M. Owen offers expertise about global security, politics and democracy. (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

Q. How is Putin’s attack on Ukraine a threat to democracy globally?

A. Putin is attacking not just the government, military, people and territory of Ukraine, but also Ukrainian democracy. Ukraine has never been a stable constitutional democracy; it is better to say that it is an aspiring democracy. But Putin does not want successful democracies on Russia’s border, and he is taking aggressive steps to keep constitutional self-government far away. Having democracy next door undermines his own authoritarian regime in Russia. And free-market democracies, at least in Europe, tend to be carriers of American influence and power. It is pretty clear that Putin wants Ukraine to be like neighboring Belarus – a pliable authoritarian country.

If Putin succeeds in Ukraine, it certainly will not doom democracy around the world or even in Europe. But we have much research that suggests that domestic regime types, including liberal or constitutional democracy, tend to spread and contract in waves over time and geographic space. Political regimes spread through a number of mechanisms. One is by setting a successful example, such as when democracies sustain economic growth and stability. Another is by a kind of osmosis: social contact across borders can have effects. A third is by active promotion, usually by a great power – such as what Russia is doing now. A fourth is through contagion, such as happened in the Soviet satellite states of Central Europe in 1989. Finally, international rules and institutions can, depending on their content, favor democracy or authoritarianism. Since World War II, and especially since around 1990, they have favored free-market democracies – although they clearly need reform today.