‘Inside UVA’: This Professor’s Blackboard Is the Lens of a Camera

January 25, 2024 • By Jane Kelly, jak4g@virginia.edu Jane Kelly, jak4g@virginia.edu

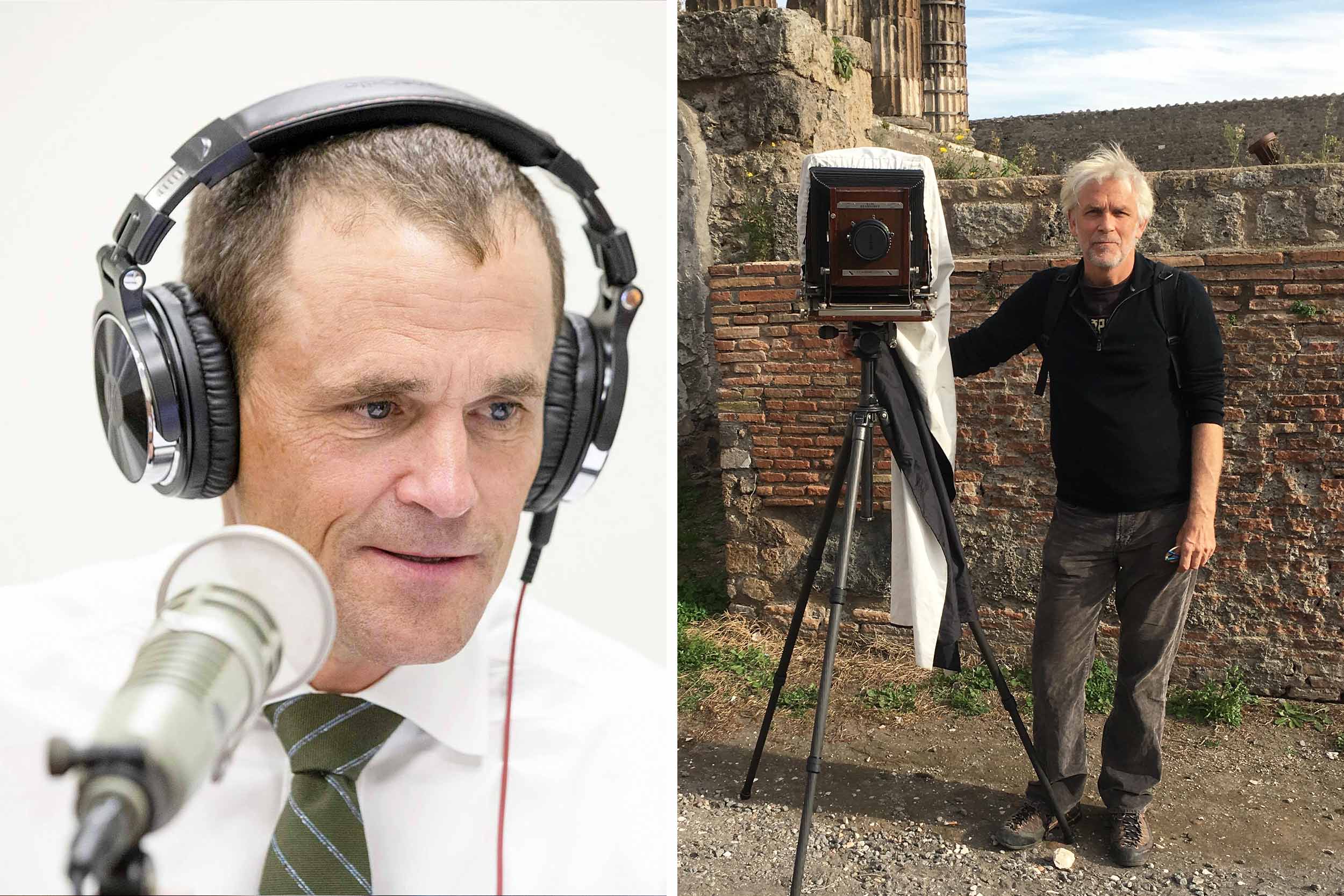

UVA’s Commonwealth Professor of Art, Bill Wylie, is President Jim Ryan’s podcast guest this week. (Photos by Dan Addison, University Communications and Jane Haley)

Audio: ‘Inside UVA’: This Professor’s Blackboard Is the Lens of a Camera(31:15)

Listen to how this celebrated professor of art composes photographs. The secret, Commonwealth Professor of Art Bill Wylie says, is to “make” a photograph, not “take” one.

Bill Wylie, Commonwealth Professor of Art: What I love about photography is it’s going to always have that representational aspect. The marble quarries of Carrara are going to be in front of me, a tree from the Colorado plains is going to be in front of me, but I’m dealing with the frame, I’m dealing with the four edges, and what takes place in the middle of that. Once it’s hanging on the wall, or in a book, it’s about that place, but it’s also about the experience of the work of art.

Jim Ryan, president of the University of Virginia: Hello, everyone. I’m Jim Ryan, president of the University of Virginia and I’d like to welcome all of you to another episode of “Inside UVA.” This podcast is a chance for me to speak with some of the amazing people at the University, and to learn more about what they do and who they are. My hope is that listeners will ultimately have a better understanding of how UVA works, and a deeper appreciation of the remarkably talented and dedicated people who make UVA the institution it is.

I’m joined today by Professor Bill Wiley, a renowned artist and photographer, and the Commonwealth Professor of Art at the University of Virginia. Through his art, Bill investigates place, exploring what constitutes a place and how places are informed by physical features, human interaction and time.

His art can be found in the permanent collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery, the Smithsonian Art Museum and the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. He has published seven books, served in various leadership roles in the art department, and has directed UVA study abroad program in Italy since 2007.

Bill has been an extraordinary member of UVA faculty for over two decades, and today, we are incredibly fortunate to have him on the podcast. Bill, thank you for being here.

Wylie: Thank you for asking me.

Ryan: So, like everyone else, I’m a bit of an amateur photographer, so I’m especially excited to be speaking with you. I want to start at the beginning. You had what I think it’s fair to say a sort of unusual path to academia. Yes? And I’d love to go back and trace it with you.

So, you were raised in the south side of Chicago. Is that right?

Wylie: Yeah, I would, I would say the south-south side. So right where suburbia sort of starts to creep into the urban texture of the south side of Chicago.

Ryan: And was it there that you became interested in photography? Or was it later in life?

Wylie: It’s interesting because I started making photographs when I was there. You know, as a kid, I remember getting an Instamatic camera and taking pictures, even in the fifth and sixth grade, of friends at school, and being sort of wowed by the pictures that came up. But I never really thought about photography as something to do, other than just a fun little thing on the side.

When I was in high school, my sister was the editor of the yearbook. And when I was, at first, a freshman in high school, she wanted to get me involved in things at the school. So she told me to come by the yearbook. And the guy who was the faculty adviser, he stuck a 35-millimeter camera in my hand and said, “Go make interesting photographs.”

I had no idea what that was. But I wandered around, made some pictures. He got sort of excited about it. And I thought, “Well, this is kind of cool. You know, maybe you could do something with this.”

And I started taking pictures then from then on, but I would say it was quite a bit later before I thought to make it my life’s work.

Ryan: Yeah, right. So, from high school, you went to college in Colorado?

Wylie: Correct. Not right away, though. I moved out to Colorado to rock climb. So like, I started rock climbing in high school, and, you know, I did not know what I really wanted to do. But I wanted to do some kind of science like geology or something. So, I thought, “OK, there’s lots of rocks and culverts. I can climb them, and I can study them.”

And, and when I got there, I realized that I needed to, I mean, I was pretty ignorant about how college worked. But I realized, “Oh, I better become a resident of Colorado before I go to school here.” So, I moved there, started working jobs, was climbing, doing things I wanted to do there. And it took me about eight years to get back around to going to college.

Ryan: No kidding!

Wylie: Yeah, yeah. So, I was, all I was doing was traveling and climbing and making photographs.

Ryan: So what years were this?

Wylie: Let’s see, I moved to Colorado in 1976, and so went back to school. ... So, eight years is not the exact right – because I went back to school first just to take a single class in photography at Colorado State University. I was living in Fort Collins, and I thought, “You know, I’ll take, I’ll sign up as a continuing ed student –“

Ryan: – right –

Wylie: – “take a take a class, learn a few things about the dark room, and then get on my way to becoming a professional photographer.” But one of the reasons I’m a professor is because in that class, the teacher just blew my mind as to the possibilities of what things could do.

So, the next semester I took another continuing ed class, and then by the time the third semester rolled around, I was like, “I should just get a degree in this thing. This seems like something I can stick around and do.” And I was very excited to do it.

Ryan: That is so interesting. So, this was not a really well-formed plan from the time you were 9?

Wylie: No, not at all, not at all. It was, you know, it was one of those things that the enthusiasm of my teacher, the work that he was introducing me to, and the environment of academia were all things that I realized I wanted in my life and I wanted to be around. You know, people engaging in ideas and working out interesting concepts. It was just very exciting, and I was thrilled to be part of it and realize that that’s the life I wanted. I sort of fell into it.

Ryan: So, can we go back to rock climbing for a second? How big was rock climbing in the mid- to late 1970s?

Wylie: It was actually huge. Yosemite Valley was the mecca of climbing in the world, really, climbers from all over the world came to America. It was – you know, I started climbing in high school just as a way to get out of Chicago. I joined an outdoor club because they took trips to Wisconsin. And so when I graduated high school, I realized I just wanted to continue it. And the best place seemed to me to do it would have been Colorado. But it was very active, I was really involved in it. I mean, it’s pretty much what I did, every job I did. I worked on oil rigs, or in restaurants or things like that, and it was all just to make enough money to go someplace and rock climb. I spent easily six, seven months of the year rock climbing.

Ryan: I think I told you when we last met that my oldest son has caught the bug of rock climbing as well, and, in some respects, is trying to build a life around it, as well. What did you find so captivating about it?

Wylie: Both the physical and the mental aspects of it. I mean, it was problem-solving, you know, trying to figure out how to do the climb. But it also required physical skill, but not even necessarily strength. Like, one of the things I loved – I mean, I’m a pretty physically active person – but I never considered myself to be super strong. But you had to learn balance and strategy and moves, and all of that was super exciting. Of course, on top of it all, I love being outdoors.

Ryan: Do you still climb?

Wylie: Here in Virginia, I mostly climb in gyms. I go to a gym and climb in Richmond. I love, still, the physical of it. You know, once you get to be my age, it helps with your balance and things to be able to do those moves. But the motion of climbing is really spectacular. I love it.

Ryan: So back to photography. So you’re in school, and are you thinking at that point that you’re going to become an academic, or are you thinking you are going to become a professional photographer, or both?

Wylie: It’s interesting. I realized that the great thing about academia was that if I continued in it, it was – and, by the way, I had no idea how difficult that was going to be that I would be surrounded all the time with just photography. You know, I looked at my teachers and I looked at other people who I respected in the field, most of whom were professors at various schools. And I thought, all they get to do all day long is sit around and talk about photography, and then they get to make their photographs, and that’s, that’s 100% their life. So, I realized early on, that’s the path I wanted to follow. But first and foremost was the idea that I wanted to be an artist and I wanted to do something with the work. So, it was more that I saw academia as a path that was going allow me to be 100% immersed in the life, but also support what I wanted to do.

Ryan: At what point did you realize you had some talent in this? Was it someone else who told you?

Wylie: That’s a question that still lingers out there. But I would say, I think when I was in that undergraduate program.

Again, let me put that into a context of, I was a little older than the other students by the time I started in that program, but I very quickly connected with the work of a few other photographers who weren’t necessarily, who weren’t my teacher at Colorado State. And I started to try to emulate their work to try to study their work and learn things from it. I reached out and connected to those people, you know, and I was like, “Can I can I show you some things that I’ve done?” When those people started to be to respond in a positive way – nobody said to me, “Oh my gosh, you are you are fantastic.” But people would say, “This is interesting,” you know, or, “I like what you’ve done here.” Which is, of course, how I learned to be a teacher, was watching these people react with me. And so I thought, “OK, if somebody finds this interesting, I think maybe what I’m doing has some potential and, and I’m just going to keep working in that direction.”

Ryan: When you say they found some things interesting, I’d like to pause on that for a second. Because I think for a lot of us who are not experts in photography, it is a little hard to – we see images that are arresting, are beautiful, to our own eyes. But what makes or what made your photographs, if you remember, interesting to those who are experts in the field? What are they looking for?

Wylie: Well, it’s a great question. It’s something that I struggle with a lot trying to help students understand this, because we have such a sense that a photograph is a representation of the thing that was in front of the camera.

But what a photograph is, and I think what some of my work was doing, and what I tried to do in all my work, really, is to have the photograph transform what was in front of the camera into something even more interesting. Of course, that happens through a lot of technical things, not the least of which – while this is more of a dimensional thing – but it’s putting the three-dimensional world into a two-dimensional space. When that space gets compressed, suddenly interesting things happen.

And that was something that I picked up on really early in making photographs – that what you could do with the background and the foreground by compressing them would be different than if you were standing in front of those things. So, when you do that well, in an interesting way, it becomes, you know, a compelling part of a photograph. And I think that really is what’s required for a photograph to become a work of art, is that transformation and somehow towards something new, right, something surprising,

Ryan: Right. And I noticed that several times you’ve referred to “making a photograph” rather than “taking.” Is that what you’re getting at when you say you make a photograph?

Wylie: Absolutely. And again, this is something I learned from my early mentors, but it made perfect sense to me. You know, when I work with a camera, I think about the composition; I’m putting parts together. It’s a picture problem that you’re developing in there in a way that’s very similar to if I was standing in front of a blank piece of paper and deciding to make a drawing, you know. I’d make a mark here, I’d make a mark there, I think over here in the corner, it needs something I need to sort of balance this over here. I’m looking through the viewfinder and I’m doing that exact same thing.

Ryan: Right.

Wylie: I sort of don’t like the concept of “taking,” You know it’s got a little bit of a negative connotation. So “making” is also, it’s almost empowering in a way. You know, it’s something I always talk to my students about. They end up usually asking me the same question that you just did, or pointing out the same thing that like “you’re talking about making?” And I’m like, “That’s right. That’s what I want you to do. I want you to make a picture, you know, be involved.”

Ryan: So you’ve seen huge changes in technology related to photography, from the time that you began with an Instamatic to –

Wylie: One-twenty-six cartridge film, that 126 cartridge, you just plug into the back?

Ryan: I remember, yeah. Now, you can take an almost unlimited number of pictures. Do you feel like the degree of difficulty of producing a great photo has lessened any, since you can take 1,000 photos, where in the past you are maybe limited to 10 to 50 shots?

Wylie: It’s a good question. I don’t know if it’s gotten any easier, because a good photograph is still going to have to have structure; it’s still going to have to have all the things combined.

When I was working on say, Pompeii, or Carrara, a couple of projects of mine, I was using an 8x10 camera and I had film holders that had individual sheets of film in it. I would go for the day in the quarry, and I would have only 18 sheets of film with me for the entire day. So I oftentimes would set up the camera, spend 20 to 30 minutes getting everything composed, and then I’d have to say, “Is this film worthy? Is this is this worth a sheet of film?” And so I probably lost some pictures, some good pictures, because I talked myself out it.

Whereas with digital photography, you can take that picture and move on and not worry about it. So it’s possible that that more pictures are made, because they’re not worrying about the film, but I don’t necessarily think it’s easier to make a good picture, right?

Ryan: You mentioned Carrara and Pompeii, and I’d love to talk to you about some of your projects. So I’m curious, what draws you to a particular project? You spent time in Carrara and Pompeii; you spent time with, was it a six-person football team in eastern Colorado?

Wylie: Yeah.

Ryan: How do you decide, “OK, this is what I want to photograph”?

Wylie: Well, as you pointed out in the introduction, I find myself very interested in the concept of place and how a photograph, or how artwork can communicate some information about a place. Photography has this great ability to deal with the details and the specifics. So that’s one of the things I love about it.

But almost always, it’s the visual quality of the thing. I’ll talk about Carrara, for instance. The quarries themselves are these magnificent structures that are like cubist paintings, like something Paul Cézanne would have made on a canvas. And then there’s this incredible light from the Ligurian Sea that transforms the place into shadows and walls of glimmering white. It’s absolutely beautiful. But then I love the fact that this history of Carrara was there, and maybe there was some way to sort of talk about that through photography. So not only make these visually arresting, transformative photographs, but also deal with the sort of historical nature of it. I mean, Carrara has been in use since the Etruscan time, right? And the Romans, up to the renaissance of Michelangelo. And still, they’re taking marble out and making fantastic works of art – Louise Bourgeois and other people still working in those quarries.

Ryan: And there’s a connection to UVA, with Carrara?

Wylie: That’s right. Yes. After I had produced that work, I was walking across in front of the Fralin Museum one day, and I saw these two Italian guys doing a 3-D scan of one of the old capitals that sits in front of the museum. I heard him speaking Italian, so I went over and said, “Come va,” you know, I started speaking Italian to him, and then they said they were from Carrara, and then they pointed out that they had been charged with, you know, making remaking the capitals for the Rotunda.

So I went to Jody Kielbasa, and I said, “You know, I just did a bunch of work there, I’d love to try to figure out a way to document what these guys are doing.” So I ended up going to Carrara two or three times filming the studio, making the capitals and making a series of photographs documenting it. It was amazing to watch them, you know, bringing the stone down from the quarry, right, and then working with photographs and their 3-D scans of what existed from the old capitals, of modeling and clay what was going to be the new capitals, then scanning those and working with the machines that carve out the basic forms, and I got to be there while they were putting the capitals on the Rotunda when they brought them back to Virginia.

Ryan: So tell me a little bit about the six-person football team.

Wylie: So that project, you know, you asked about how I pick an idea – that Eastern Colorado space, that prairie space out there is something that, ever since I’ve moved to Colorado, I was absolutely in love with. Just that wide-open space. I made a whole series of tree photographs out there, and I’ve done other things.

But one time, when I was leaving Colorado at the end of summer to drive back to Virginia to start the semester – I had an old pickup truck that didn’t have any air conditioning in it, so I would drive in the evenings as much as I could – and the sun was setting, and it was getting pretty dark and I was driving down this road, and I saw this beautiful green field glowing off in the horizon. It was just like a beacon. So I drove over to it, and there was a guy out there watering the grass. It’s normally just brown and dead out there, and this green grass was there. So I started talking to him, and he said, “Oh, this is where the prairie football team plays, you know, it’s a six-man football team.”

And I was like, “Six-man?”

I just learned a little bit about it, and I had a sabbatical coming up the next fall, and I just decided: You know what? It would be cool to embed myself in this little town with this school. Kindergarten through senior in high school had less than 150 students in it. This is why it’s six-man football, right? If there are fewer than X number of students, they can play this particular type of ball. So the next year I went out there, I got a residency in Fort Collins that I knew where I could stay, and every day I drove out to the prairie and filmed from their first day of practice ’til the last game of their season.

So I made a video that I’ve made a couple of short films with, but I was also photographing. I was really interested in how the life of that school, and in particular those boys on the football team, said something about the place. So once again, I was trying to use the human interaction, the human element to speak about the place.

A lot of them lived on ranches; I went out to the ranches, but there was a certain character of the space in the photographs and the films, that I made that I tried to, be a part of this expansive, like, universe that’s just endless horizon, as far as you can see, and not a tree in sight. But then here’s this football game that’s being played on Friday nights under the lights, that’s just ranchers and roughnecks from the oil rigs and families out there.

One thing that was kind of amazing was that they would park with their trucks, mostly trucks, pointing toward the field, and people would sit in their cars, because it’d be kind of windy and cold out there as the winter as the fall progressed, and when a touchdown would happen they would all honk their horns and flash their headlights. That was a sort of celebration. It was, it was amazing. It was really amazing out there.

Ryan: How did this community feel about being photographed by this guy from UVA?

Wylie: The embraced it, they got into it. I remember at one point, there was a – the only sort of odd thing that happened, was early on, at one of the cars – there was a lot of potlucks and things with all the families and the coach would be talking to the families and the players would be there. And I was at one of them, and somebody stood up and did a sort of pre-dinner prayer. I was filming this and afterwards, one of the family members came over and said, “You’re not going to like make a point about that prayer –”

Ryan: Oh interesting.

Wylie: “ – and turn this into of, like, conservative, you know, crazy Christian thing?” And I was like, “You know what, that’s the least of my interest. You know, I’m interested in your son and the players and what they do out there and the life they have, and this space.”

But otherwise, everybody was very – they embraced what I was doing to the point that, the summer after I did it, after I made the film, one of the boys who was one of the more popular boys on the team was killed in an auto accident.

Ryan: I’m sorry to hear that.

Wylie: Yeah, it was very sad. The book is dedicated to him. But his family reached out for a lot of photographs that I had. They were able to make a big installation at the school based on some of the work that I had done, because, unlike me in the fifth grade, a lot of kids aren’t thinking about documenting their own lives. Maybe that’s changed a little bit now with cell phones. But they still they don’t think of the pictures or making pictures to have a memory in any way, and so there was nothing but except what they might have had from me.

Ryan: Do you think it enhances your photography when you know your subjects well? Or does it create an obstacle, because you know your subjects well?

Wylie: Interesting, that’s an interesting question. I would say, for me, it’s a little bit of both. I like to be surprised; I like to sort of go in wide-open and say, “Oh, look at that over there. Look at that over there. That’s interesting,” or “How can I do this?”

But I usually go back to places time and again. So, for instance, the football project, obviously, was one very long season. I had plenty of work, I mean, I was there for four months. So, I learned a lot as that was going on. But for something like Carrera, or Pompeii or some other projects I’ve done, I go back a couple of times, at least, because I learned something from the first work I make, then I figure out what maybe I should study that would maybe help me learn a little bit more. Pompeii was a great example of that – like, learning and figuring out what else was there to photograph than what I could find just wandering around on my own, you know, in the beginning.

So, I guess what I would say is, you know, the initial surprise, the initial fascination with newness is always great. But then I want to be able to go a little deeper. You know, in my case, I feel like it’s very important for me to always stay a little innocent of what’s possible and still have an element of surprise.

Ryan: And I’m curious – I don’t know if this question will make sense – but is one of your goals, with your photographs, to get at what you might call a deep truth about the place that you’re photographing? Part of the reason I asked is because in the beginning, you talked about how you can manipulate a 3-D space once it’s represented in a 2-D space. Is that manipulation a part of an effort to show something that, maybe, is even more real and more truthful than you might see with the naked eye?

Wylie: I do understand the question. I guess the first thing I’d want to say is that I don’t think about it necessarily as manipulation, OK?

Ryan: OK, fair enough.

Wylie: It’s just something, it’s just something that happens, you know, when, when a photograph, it just compresses the space. So, it’s more, as the word I used before, of a transformation, that is usually somewhat of a surprise.

Ryan: OK, I see.

Wylie: And I say that it requires me to figure out the best way to present that. Maybe I move to the left, maybe I move to the right, maybe in the dark room, or on Photoshop I enhance something or bring something out. But I try to not show my hand in terms of what maybe you would maybe call manipulation in photography.

But to the real depth of your question, I guess what I would say is: I’m trying to make a work of art. In doing that – and this is why I chose to be a photographer – I’m interested in the thing I photographed, but I’m also, I would say, more interested in the thing I’m making.

So, what I love about photography is it’s going to always have that representational aspect. The marble quarries of Carrara are going to be in front of me, a tree from the Colorado plains is going to be in front of me, but I’m dealing with the frame, I’m dealing with the four edges, and what takes place in the middle of that. Once it’s hanging on the wall, or in a book, it’s about that place, but it’s also about the experience of the work of art. That’s the kind of quality of attention span.

A great concept one of my mentors introduced me to was this notion of the quality of the attention span you bring to something. I think I’m trying to enhance the quality of the attention span a viewer would bring to my photograph, but not necessarily feeling like it’s going to make the place more real or more powerful. Hopefully I’ve positioned myself in such a way that the great thing about the place is just there to begin with, where I choose to stand.

Ryan: Unfortunately, we’re close to time, I could talk to you for hours, so let me ask you just a couple of final questions. One is, what are you working on now?

Wylie: Well, I’m in the middle of editing a book about Japan. I did a pilgrimage in Japan just before the pandemic, where I walked a 1,200-kilometer path around the island of Shikoku. I took a small digital camera.

You know, I was originally just going to do it for the pilgrimage’s sake; I wasn’t even going to take a camera, and one of my one of my mentors was like, “You’re a photographer. You should probably take a camera.” So, I got a small digital camera.

But what was so wonderful, because I normally work with big cameras and large things, but it was much more like, not to overuse the word, but snapshot. It was more like I was making sketches of every little thing I saw versus the setting up. So now we’re putting together a book of about 120 photographs taken on that journey.

I’m also writing some things and so that’s, that’s the current project. That’s what’s going on.

Ryan: My guess is I’m not alone in admiring your work, but also being envious of what you get to do for a living. For those who are interested in following in your path, what advice would you have for someone who is interested in photography and is interested in becoming an artist like yourself?

Wylie: Well, obviously, you just got to do the work. Making pictures, trying to show them to people whose opinions you respect, and to try to get your work out in the world – that’s a very difficult thing because, as you pointed out early on, there’s a lot of people who make photographs. To try to stand out somehow you have to not only make interesting work, but put it in front of the people who are going to help you put it in front of other people. That has become much, much more difficult to do.

It wasn’t easy to do when I first started out, but comparatively, it was a lot easier to get your foot in the door and have a museum curator say, “Oh, that’s interesting. You know, I’m going to take a look at that,” or you know, “Let me buy one of those pictures.” And then they put it on the wall and then somebody else sees it.

Now often a lot of museums are buying work and it never makes it on the wall. It just goes into their archives. So, I guess I would just, you know, the simplest thing is to just – what was that saying that was like, “dress up and stay home,” you know? Like, do the work and then hope that something comes from it once it starts to get good. That’s a pretty bad answer.

Ryan: No, it’s a real answer and an honest one. Well, Bill, thank you so much.

Wylie: Thanks, Jim.

Ryan: It’s been a total pleasure to speak with you.

Wylie: Same here, same here – I really appreciate it.

Aaryan Balu, co-producer of “Inside UVA”: “Inside UVA” is a production of WTJU 91.1 FM and the Office of the President at the University of Virginia. “Inside UVA” is produced by Jaden Evans, Aaryan Balu, Mary Garner McGehee and Matt Weber. Special thanks to Maria Jones and McGregor McCance.

Our music is “Turning to You” from Blue Dot Sessions.

You can listen and subscribe to “Inside UVA” on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts. We’ll be back soon with another conversation about the life of the University.

He is a renowned photographer and celebrated artist and the University of Virginia’s Commonwealth Professor of Art.

Bill Wylie’s work “can be found in the permanent collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery, the Smithsonian Art Museum, and the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts,” said President Jim Ryan, by way of introduction, in the latest episode of his podcast, “Inside UVA.”

Wylie’s specialty is photography, and he has led UVA’s study abroad program in Italy since 2007.

When discussing photography, Wylie, a member of the faculty in the College of Arts & Sciences, talks about “making” a photograph, not “taking one.”

“When I work with a camera, I think about the composition, I’m putting parts together. … That’s very similar to if I was standing in front of a blank piece of paper and deciding to make a drawing, you know,” he told Ryan. “I’d make a mark here, I’d make a mark there, I think, over here in the corner, it needs something; I need to sort of balance this over here. I’m looking through the viewfinder and I’m doing that exact same thing.”

“It’s something I always talk to my students about,” he said. “That’s what I want you to do. I want you to make a picture – you know, be involved.”

You can learn more about Wylie’s artistry and scholarship – including his work in settings from Italy to eastern Colorado – by tuning into “Inside UVA,” which is streamed on most podcast apps, including Apple Podcasts, Spotify or YouTube Music.

Trending

Media Contacts

University News Senior Associate Office of University Communications

jak4g@virginia.edu (434) 243-9935