May 11, 2011 — A thick, printed anthology is required for many a college literature course. But that's so 20th century.

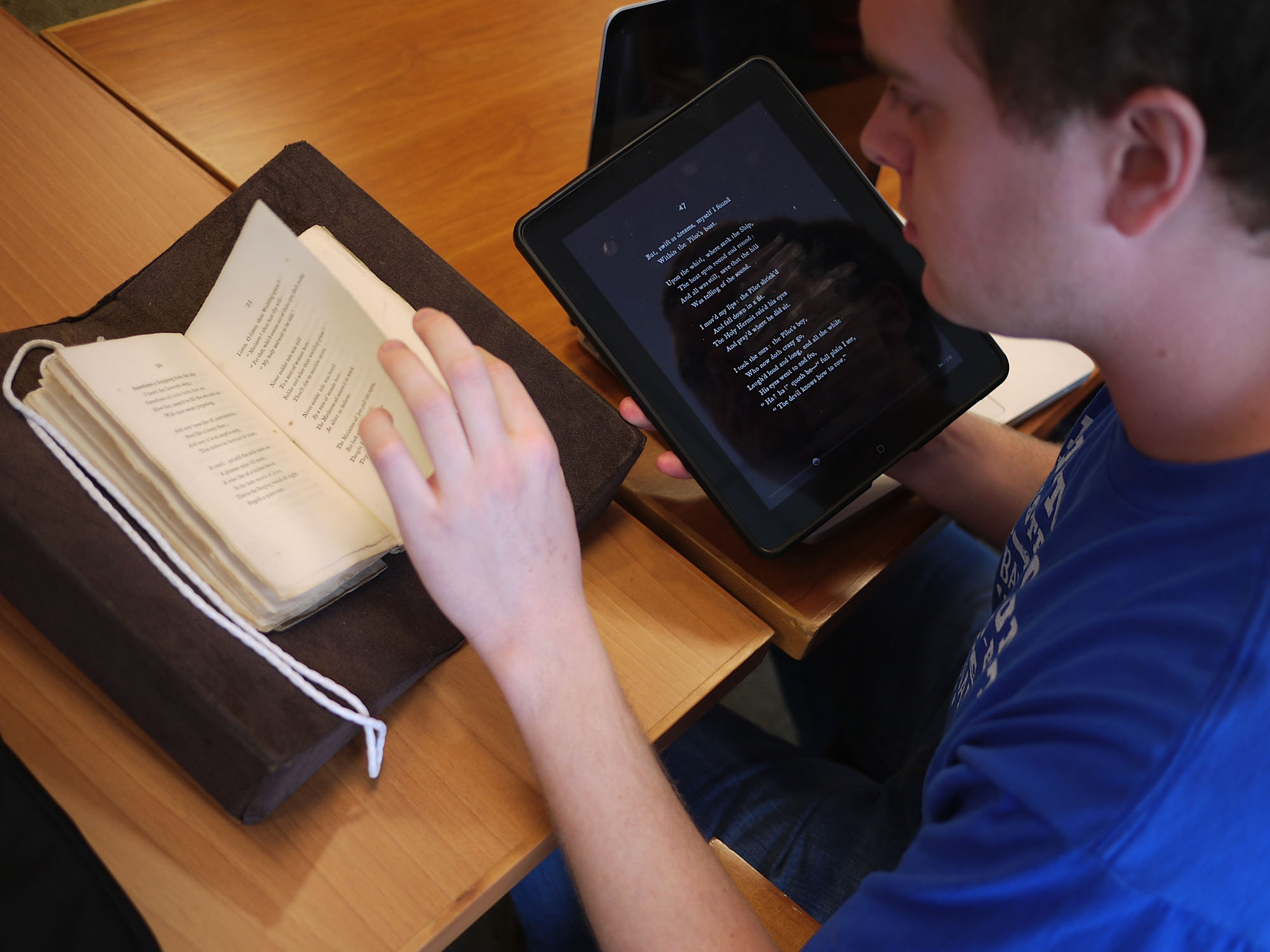

English students in the University of Virginia's College of Arts & Sciences experimented this semester with iPads to test the possibilities they offer for learning and scholarship. Imagine delving into digital representations of originally published texts, or parsing the meaning of an author's revisions to her poetry.

Thirteen students were given the iPads in one of 15 weekly discussion groups accompanying Jennifer Greeson's and Brad Pasanek's required survey course in British and American literature from 1660 to 1880. Pasanek and Michael Pickard, a doctoral student and teaching assistant who taught the section, also used iPads.

Pickard saw possibilities. "It gives students the chance to ask the fundamental questions: Where does it come from? How is it put together?" he said.

Pasanek said he and other English faculty have realized that textbooks will likely be moved to a digital format in the not-too-distant future. "It behooves us to shape the next stage before it is forced upon us by a publishing market that does not have our students’ best interests at heart." The ultimate goal is to produce a digital "U.Va. anthology" that would further illuminate authors' texts and their thinking.

Choosing and preparing materials for survey courses is a challenge. In the British and American literature from 1660 to 1880 course alone, it would take four fat anthologies to cover the time period, and they still wouldn't include all the course reading. Instead, the English department in recent years has typically made up its own printed course packets.

"Print literature anthologies have many virtues – editorial sophistication, coherence, convenience – but as a reading experience, they are distinctly lacking, as they homogenize widely variant texts into a single format," said English professor John O'Brien, who will use the iPads next in his undergraduate course this fall on the Restoration and early 18th-century British literature. "And they've always had limited capacity – they can only admit as many texts as the bindings will allow, which hardly seems a good way to go about building a curriculum or a canon."

Companies like Google, and university libraries including U.Va.'s, have already been scanning and putting on their websites millions of books – scholars prefer to call them "digital surrogates."

"This generation and the next will more and more be looking online at page-scans of old books, keyword searching in electronic text databases and moving between Google Books and the rare books archived in Special Collections," Pasanek said.

"The future of the book is the history of the book."

He means "to forestall anxiety about the end of the book, the death of the novel and falling literacy," he said. "New books will take advantage of media being developed. But the new also remediates the past in ways that make the past newly available."

He and other teachers want to pique student interest in printed books by having them read digital surrogates. This activity also enables the students to learn the practice of textual scholarship, which is a big part of what English professors and other humanities scholars actually do in their research. It's analogous to science students learning how to do science in a lab.

The iPads were loaned to the students, thanks to support from U.Va.'s chief information officer, James Hilton, and Bruce Holsinger, associate dean of Arts & Sciences and a professor of English and music. The idea was to see what works and what problems arise in incorporating the use of technology, and to listen to students' feedback.

Pickard's discussion group had all the course material and more loaded on the iPads.

His [class] produced their own small editions of certain authors after studying the literature online and in print at the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library.

"The students were glad to be part of it. The project is laying the groundwork for future generations," Pasanek said.

They encountered a steep learning curve, however. Some students were nervous carrying around equipment they didn't own. Some suggested using a better format to present the texts and including publishing software that would enable students to take notes on the screen.

Another problem: software incompatibility. Students couldn’t compare 11 different versions of William Blake's "The Tyger," as planned, because the online Blake Archive is built with Java, a programming language that is not supported by the iPad.

The discussion group blogged about their experiment. Several said it seemed "unnatural" to read the original of Charles Dickens' "Hard Times" on a digital device. One person said it wasn't as easy to use the iPad in class, when Pasanek would say in lecture, "Turn to page such-and-such."

Positive responses noted that looking at works online showed "the evolution of a text."

Another comment: "The iPad permits innovation, so I think it’s important that we innovate. I think the department is heading in the right direction with its creating of the U.Va. Anthology."

Another student said he learned more doing the digital projects than just trying to absorb facts.

Pasanek and Pickard came away thinking a digital lab should be added to the survey course so students have time to learn the tools of digital scholarship.

"Each project moves us closer to this dream of having the Virginia anthology," Pasanek said.

English students in the University of Virginia's College of Arts & Sciences experimented this semester with iPads to test the possibilities they offer for learning and scholarship. Imagine delving into digital representations of originally published texts, or parsing the meaning of an author's revisions to her poetry.

Thirteen students were given the iPads in one of 15 weekly discussion groups accompanying Jennifer Greeson's and Brad Pasanek's required survey course in British and American literature from 1660 to 1880. Pasanek and Michael Pickard, a doctoral student and teaching assistant who taught the section, also used iPads.

Pickard saw possibilities. "It gives students the chance to ask the fundamental questions: Where does it come from? How is it put together?" he said.

Pasanek said he and other English faculty have realized that textbooks will likely be moved to a digital format in the not-too-distant future. "It behooves us to shape the next stage before it is forced upon us by a publishing market that does not have our students’ best interests at heart." The ultimate goal is to produce a digital "U.Va. anthology" that would further illuminate authors' texts and their thinking.

Choosing and preparing materials for survey courses is a challenge. In the British and American literature from 1660 to 1880 course alone, it would take four fat anthologies to cover the time period, and they still wouldn't include all the course reading. Instead, the English department in recent years has typically made up its own printed course packets.

"Print literature anthologies have many virtues – editorial sophistication, coherence, convenience – but as a reading experience, they are distinctly lacking, as they homogenize widely variant texts into a single format," said English professor John O'Brien, who will use the iPads next in his undergraduate course this fall on the Restoration and early 18th-century British literature. "And they've always had limited capacity – they can only admit as many texts as the bindings will allow, which hardly seems a good way to go about building a curriculum or a canon."

Companies like Google, and university libraries including U.Va.'s, have already been scanning and putting on their websites millions of books – scholars prefer to call them "digital surrogates."

"This generation and the next will more and more be looking online at page-scans of old books, keyword searching in electronic text databases and moving between Google Books and the rare books archived in Special Collections," Pasanek said.

"The future of the book is the history of the book."

He means "to forestall anxiety about the end of the book, the death of the novel and falling literacy," he said. "New books will take advantage of media being developed. But the new also remediates the past in ways that make the past newly available."

He and other teachers want to pique student interest in printed books by having them read digital surrogates. This activity also enables the students to learn the practice of textual scholarship, which is a big part of what English professors and other humanities scholars actually do in their research. It's analogous to science students learning how to do science in a lab.

The iPads were loaned to the students, thanks to support from U.Va.'s chief information officer, James Hilton, and Bruce Holsinger, associate dean of Arts & Sciences and a professor of English and music. The idea was to see what works and what problems arise in incorporating the use of technology, and to listen to students' feedback.

Pickard's discussion group had all the course material and more loaded on the iPads.

His [class] produced their own small editions of certain authors after studying the literature online and in print at the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library.

"The students were glad to be part of it. The project is laying the groundwork for future generations," Pasanek said.

They encountered a steep learning curve, however. Some students were nervous carrying around equipment they didn't own. Some suggested using a better format to present the texts and including publishing software that would enable students to take notes on the screen.

Another problem: software incompatibility. Students couldn’t compare 11 different versions of William Blake's "The Tyger," as planned, because the online Blake Archive is built with Java, a programming language that is not supported by the iPad.

The discussion group blogged about their experiment. Several said it seemed "unnatural" to read the original of Charles Dickens' "Hard Times" on a digital device. One person said it wasn't as easy to use the iPad in class, when Pasanek would say in lecture, "Turn to page such-and-such."

Positive responses noted that looking at works online showed "the evolution of a text."

Another comment: "The iPad permits innovation, so I think it’s important that we innovate. I think the department is heading in the right direction with its creating of the U.Va. Anthology."

Another student said he learned more doing the digital projects than just trying to absorb facts.

Pasanek and Pickard came away thinking a digital lab should be added to the survey course so students have time to learn the tools of digital scholarship.

"Each project moves us closer to this dream of having the Virginia anthology," Pasanek said.

— By Anne Bromley

Media Contact

Article Information

May 11, 2011

/content/ipads-help-uva-english-students-turn-back-pages-literary-history