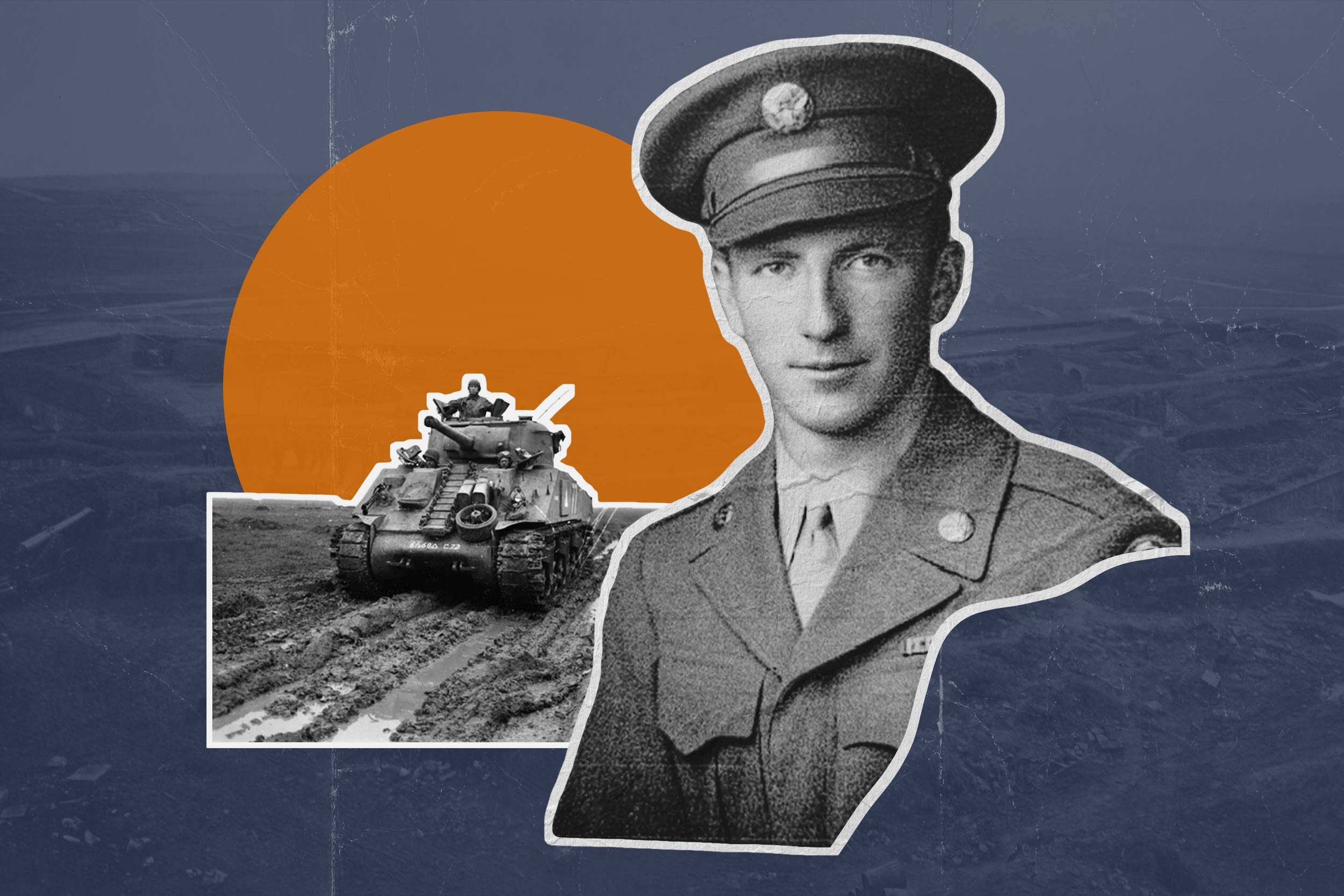

That was about to change. Mere weeks later, he and his fellow soldiers would fight to push into Germany through defenders who had been ordered by Adolf Hitler to hold ground “at all costs.”

Their tenacity and eventual victory won the Americans the nickname “Iron Men of Metz”; Patton said later that it was the most difficult fight he ever directed.

A few months before the Battle of Metz, Taylor and 8,000 other soldiers traveled from Boston to Liverpool, England, on the ship SS Mariposa. He spent eight days onboard, not knowing a single soul. Neither did he know that the reason the ship zigzagged across the ocean was to avoid the German submarines that abounded in the area, and that the Mariposa didn’t have the usual warship escort that other troop ships had.

“It broke me down because it was so unknown. I was seasick and we knew there was no way out,” Taylor, who became a sergeant, said. “Yet the experience strengthened my faith.”

Taylor felt that it was his duty to serve. His mother sent three sons, including him, to war, telling them that they had to go.

The division made its way to Omaha Beach a few weeks after D-Day, only to find they were stranded, with no fuel for tanks or trucks. Still, it didn’t take long before they were put into action. By late September, the division began its assault on a series of forts along the Moselle River.

Hitler, seeing that the Americans could easily enter the Saar region of western Germany, ordered the fort commanders to hold their position no matter what. That made the going even tougher for Taylor and his colleagues, who would spend the next two months battling for Metz before finally overrunning the German positions.

The division moved on, fighting through Germany and into the Netherlands during the next year. By war’s end, 1,205 soldiers in the division were killed, 4,945 were wounded, 61 missing in action and 380 were held as prisoners of war by the Germans.

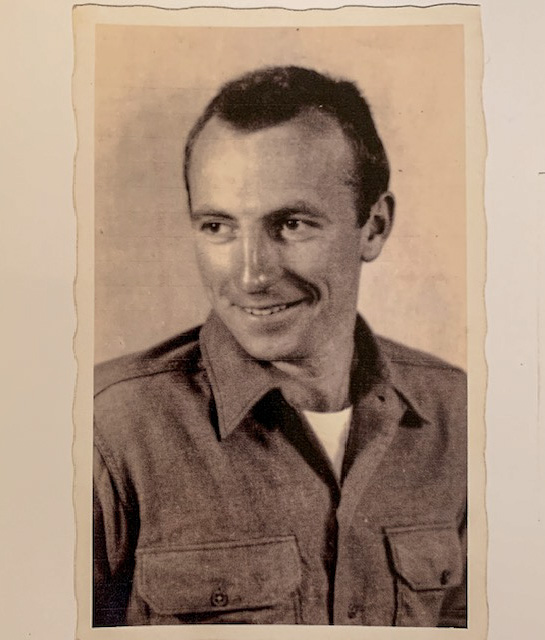

After World War II ended in 1945, Taylor said attending UVA’s School of Medicine helped him transition back to civilian life. “It gave me a sense of purpose and direction,” he said.

Taylor received his M.D. from UVA in 1950, was an intern at UVA Medical Center, a fellow at the Cleveland Clinic, and even served as an instructor in neurology back at the UVA Medical School in the ’50s. He went into private practice until 1993. He fully retired from medicine in 2003, after spending nearly a decade working at Sentara Martha Jefferson Hospital and at the Charlottesville Free Clinic. He was even asked to appear in a period film, but production was canceled due to the pandemic.

In September, Taylor celebrated his 100th birthday with his family. Nearly 80 years after the war, he looks at contemporary society with a mixture of concern and hope.

“It is unsettling to see the oppression of people’s rights to live in peace and to be able to practice their cultural and spiritual disciplines in a democratic system,” Taylor said. “I may be old-fashioned, but I’d like to believe that we, as Americans, continue to support other countries’ rights for freedom.”