In the late 15th century, Leonardo da Vinci sketched a series of grossly exaggerated portraits. With a hurried hand, he rendered profiles marred by protruding noses, distended brows and sunken eyes.

Given da Vinci’s propensity – and talent – for perspective, it’s tempting to cast these sketches off as honest portrayals of, simply put, unattractive models. They are not. Instead, they are the opening lines of a joke that’s been told for over 500 years: caricature.

Practiced by celebrated artists and activists alike, from Benjamin Franklin to Honoré Daumier, caricature has recorded and shaped many of history’s most divisive and complex conversations. Nowhere is this more evident – or true – than in the work of Pulitzer Prize-winning artist Patrick Oliphant.

Oliphant, who began his editorial career as a copy boy in his native Adelaide, Australia at age 18, is lauded as one of today’s most influential political cartoonists. In the span of his more-than-60-year career, he has drawn more than 10,000 cartoons, which were syndicated to newspapers around the U.S. as well as abroad.

Many of these – along with a variety of other original media – will now live at the University of Virginia’s Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library.

“The collection is massive,” Special Collections Curator Molly Schwartzburg said. “It is what we dream of when we imagine what a creative person’s archive might look like – a wide range of materials with great research potential.”

Boasting a spectrum of media from every stage of the artist’s life, it includes more than 6,000 daily pen-and-ink cartoon drawings, as well as original notebooks, sculptures and paintings.

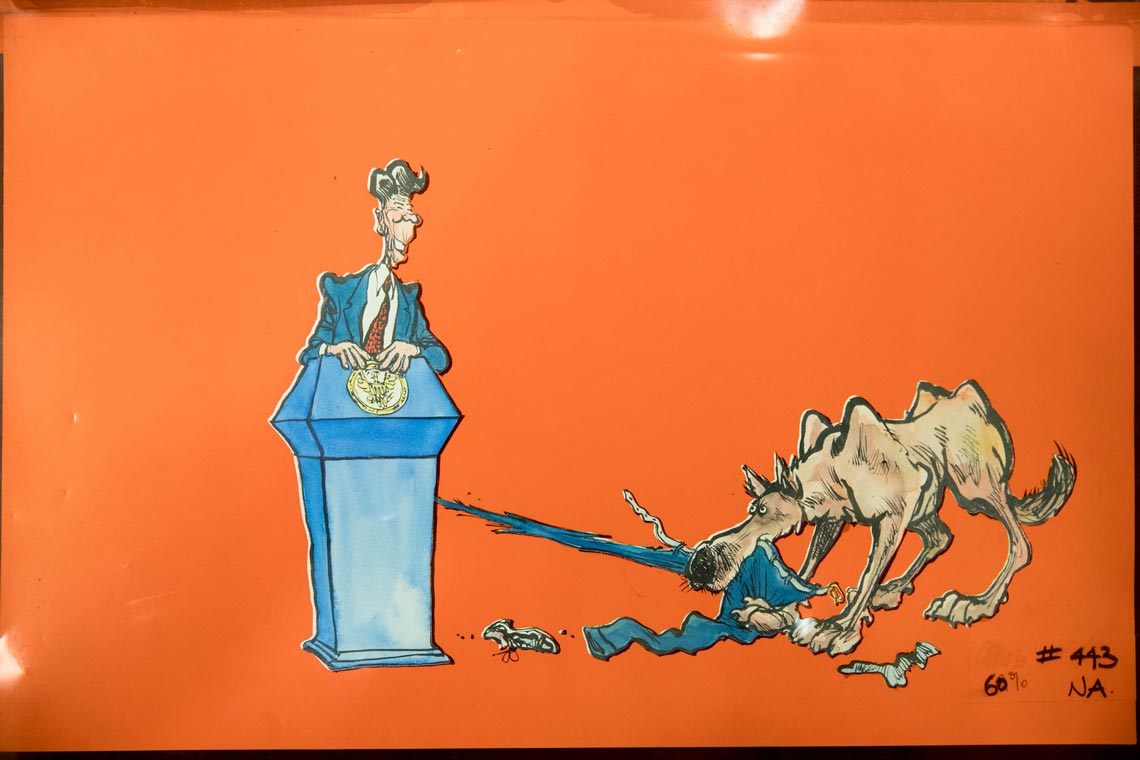

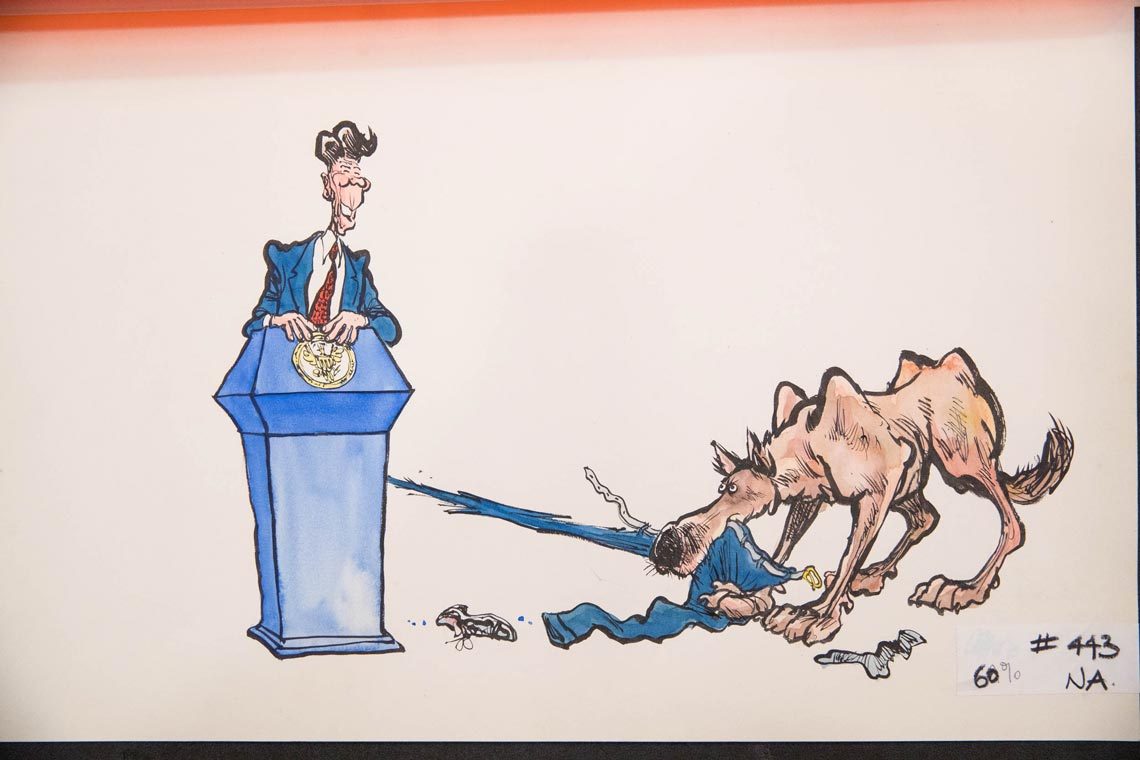

The archive’s scope of media reflects the enterprises of a true Renaissance man, including cartoon drawings, sketches, paintings and sculptures. (Photos by Sanjay Suchak, University Communications)

At the height of his career, Oliphant produced up to five cartoons a week on deadline. “Imagine waking up every morning and trying to figure out what you’re going to do and publish it the next day,” said Oliphant’s wife, Susan Conway Oliphant. Yet, his notebooks, which he kept throughout his career, do just that: offer a glimpse into a prolific artist’s creative process.

“It’s those notebooks that are really at the core of the collection. In those notebooks, you see him brainstorming,” Schwartzburg said. “A lot of those brainstorms don’t go anywhere. They don’t end up in the public eye. But understanding what does and what doesn’t and why is vital to understanding how Oliphant became such an important part of the political rhetoric of a moment.”

With searing wit, Oliphant had his finger – and pen – on the pulse of pivotal political moments.

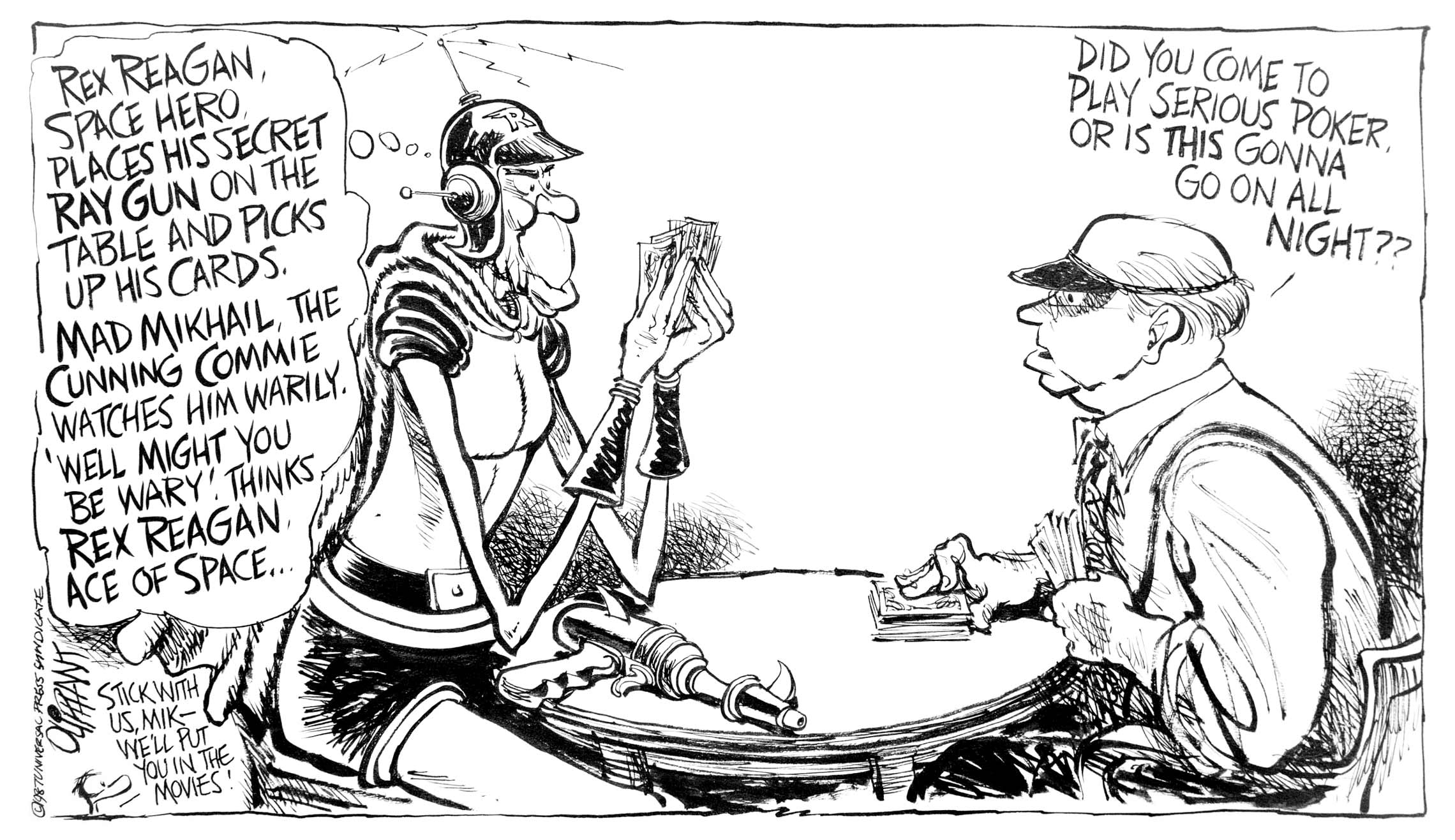

Oliphant’s voice is clear and style unmistakable. With a fervent, almost feverish, use of detail and ink, he has rendered the world’s most powerful leaders. From Ronald Reagan to Barack Obama, he approaches his subjects with an irreverence both deftly humorous and honest. One of the archives’ thousands of cartoons depicts Reagan playing poker with Mikhail Gorbachev, while Oliphant’s trademark penguin, Punk, cajoles from the lower left corner: “Stick with us, Mik – we’ll put you in the movies!”

“A lot of his work is focused on world leaders – individuals whose physical and personal characteristics he renders to comment upon something much larger than that individual person,” Schwartzburg said. “That’s his greatest skill.” While it is difficult to parse the talents of such a dexterous Renaissance man, Schwartzburg is right; perhaps one of Oliphant’s greatest skills is his ability to observe.

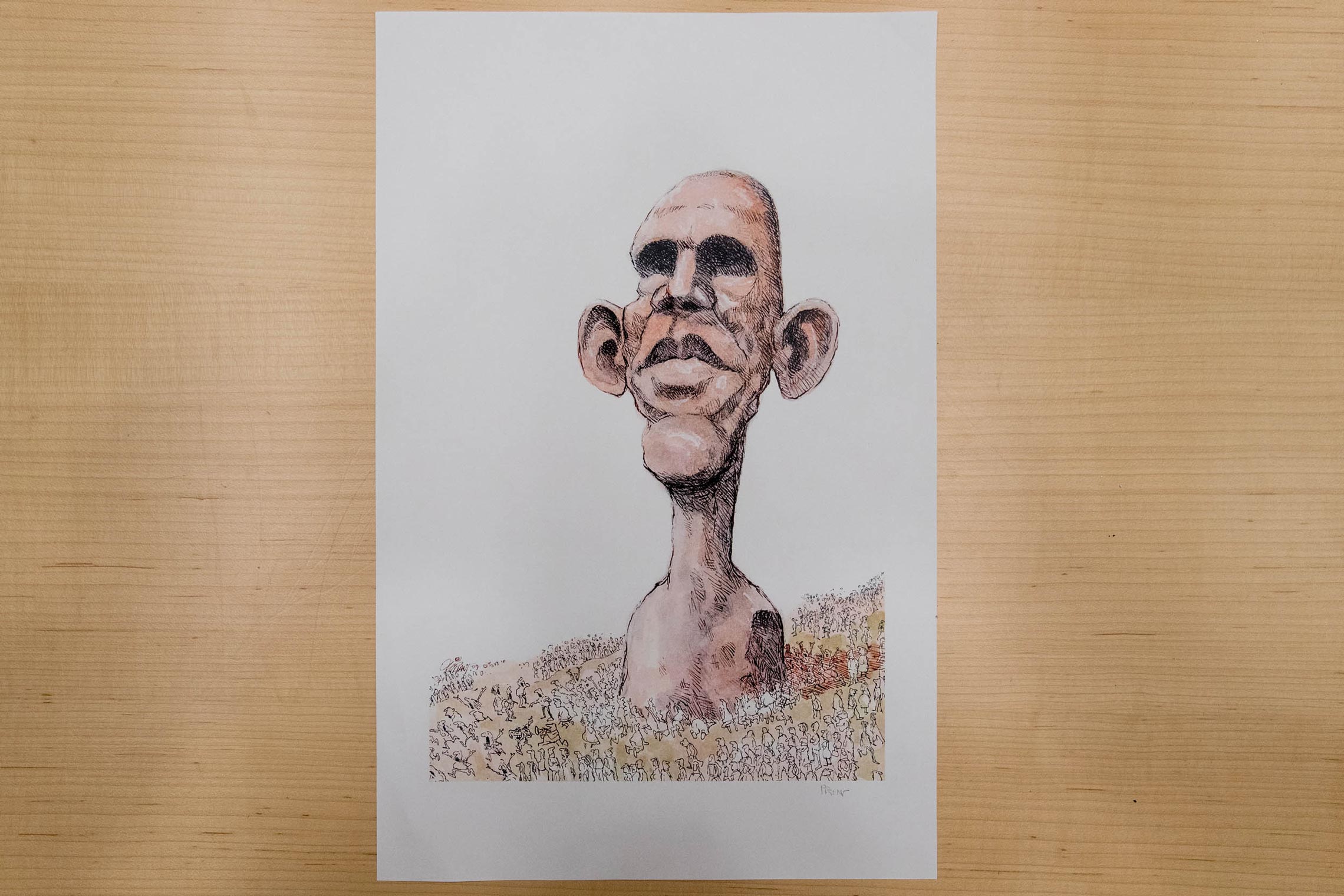

Oliphant perpetually rendered Barack Obama as an Easter Island statue, worshipped by crowds.

“It’s always been my study,” Patrick Oliphant said. “Observation. Looking at things. Which is what you do. You look at things. And remember.”

Though Oliphant has a near-photographic memory, his skill for observation goes beyond what’s visible; he distills the ethos of a person, personifying the responsibilities and expectations thrust upon them.

“One of my favorites is Obama as an Easter Island figure – as this closed-off, worshiped [statue],” Schwartzburg said. “[Oliphant] captures just how much weight was put upon Obama in the early days of his presidency – how heavy a burden of hope.”

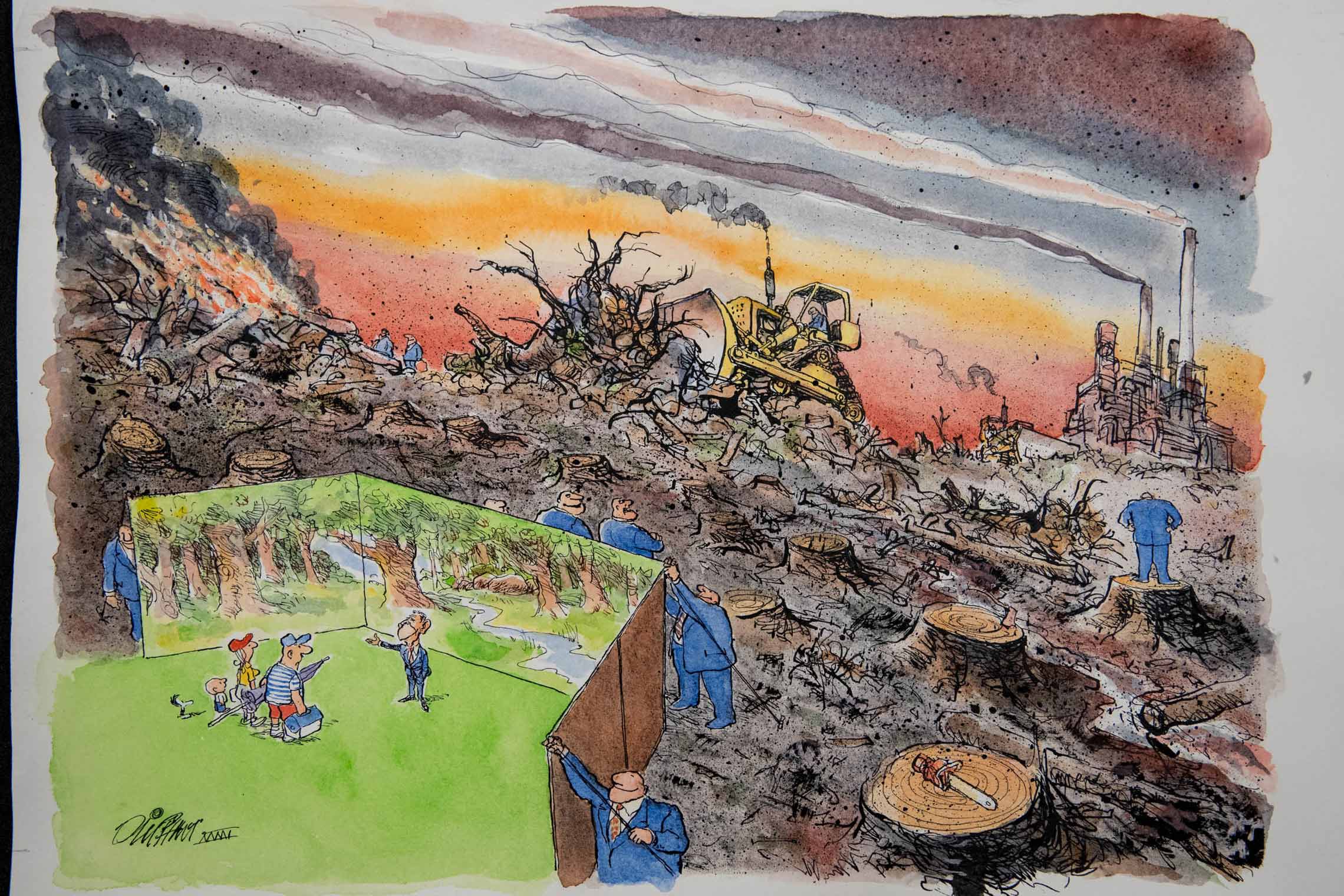

Oliphant's full-color commissioned pieces provided him leeway to do more than the confined space of the editorial page allowed.

Through his signature blend of astute observation and wry wit, Oliphant dissects both public personas as well as the sentiments of seminal political moments. With a front seat view, he observed – and illustrated – the Johnson, Nixon, Ford, Carter, Reagan, Bush, Clinton, Bush Jr. and Obama years.

“Patrick’s work represents an era when print was a primary venue for visual representations of current events.” Schwartzburg said. “This is where we saw a visual critique of our leaders – in the political cartoons that appeared in the editorial pages of newspapers.”

“Newspapers used to be the center of all sorts of things,” Oliphant said. “In my life – in most people’s lives – newspapers were what you read to know what was going on. The internet has probably changed everybody’s life. … I don’t know what the future is for this graphic art.”

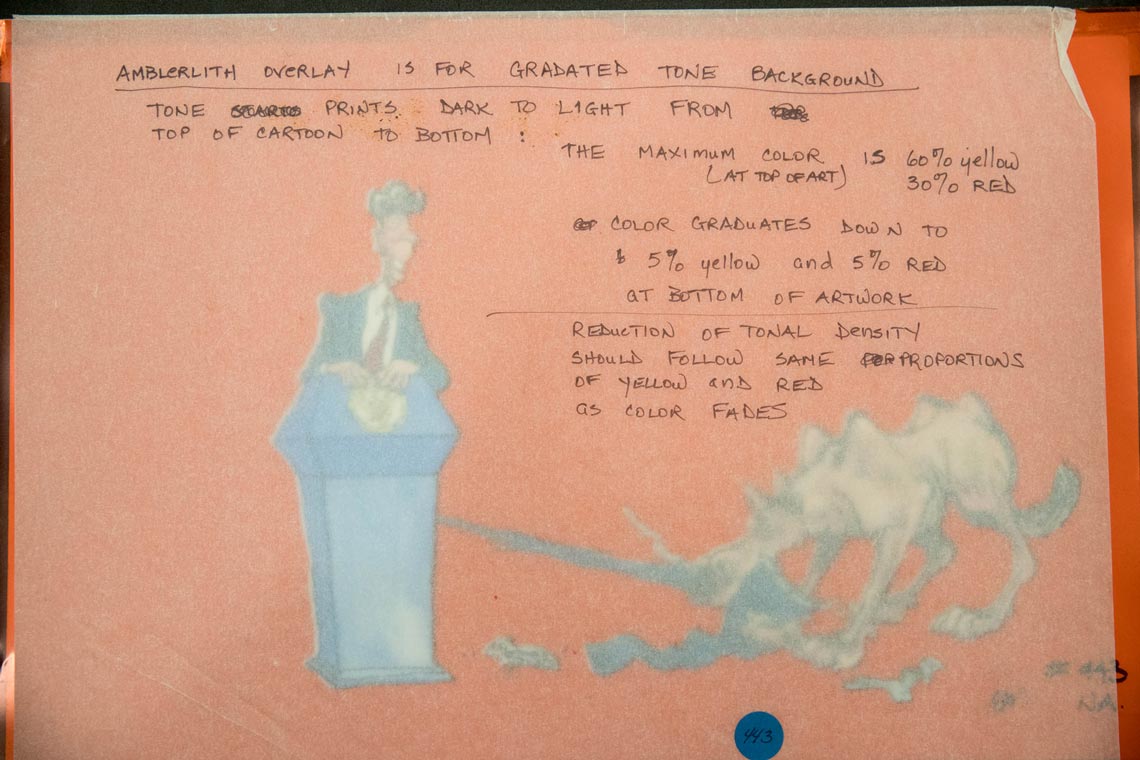

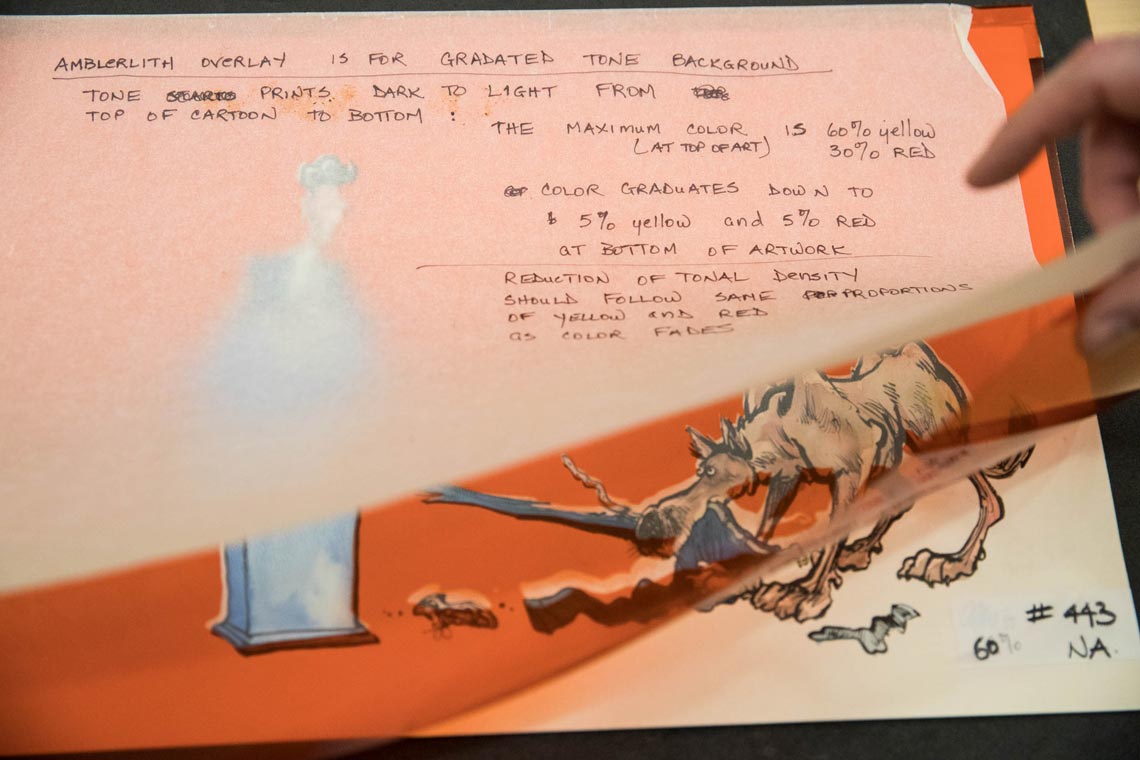

The archive includes pristine examples of past methods used to prepare color works for printing.

“We’re acquiring this archive at a really critical moment: we don’t know what the future is for this genre,” Schwartzburg said. “Now we have, here at UVA, a remarkable archive to show us what that past was, through one of the most influential editorial cartoonists of the late 20th and early 21st centuries.”

The collection’s breadth and depth are significant. Yet what is perhaps more remarkable is the pristine condition in which it was preserved.

For this, we can thank Oliphant’s wife, Susan. Conservator by trade, she preserved and maintained the collection. “Without her and her background as a conservator, we wouldn’t have what we [do],” Schwartzburg said. “Not only did she keep and arrange a huge range of Oliphant’s work, she kept it in exquisite condition.”

Oliphant and his wife Susan visited the University in April.

The archive will be available to researchers after it has been processed; the library is in the process of planning an exhibition to showcase the collection as soon as possible.

When deciding where to house the archive, Oliphant considered a host of higher education institutions. “[The University of Virginia] stands out as something else,” Oliphant said. “It seemed a natural thing to do.”

Media Contact

Article Information

April 30, 2018

/content/it-what-we-dream-uva-host-patrick-oliphants-archives