Although the University of Virginia’s Memorial to Enslaved Laborers was finished during the pandemic, and therefore has not yet had a public dedication, it has already begun to serve as a focal point for a fuller telling of UVA’s early history – and more.

As policymakers, protesters and others grapple with race and equity issues, around the nation and in Charlottesville, the memorial stands out as one way to recognize Black workers subjected to slavery and racism, and offers a place of healing as well as learning.

The word is spreading about the Memorial to Enslaved Laborers, the granite circular structure east of the Rotunda that took years to become reality and honors those who had no choice in working to build and sustain UVA in its early years. Whether it’s for an impromptu gathering of a “White Coats for Black Lives” protest of racial injustice following the death of George Floyd or for small numbers of people venturing out to visit as quarantine guidelines shift, the memorial is beginning to serve its purpose.

The circular shape of the memorial echoes broken shackles and also the “ring shout,” a traditional dance of enslaved African Americans. (Photo by Sanjay Suchak, University Communications)

Recent reviews in major publications are drawing attention to the memorial. They describe the collaborative design process, how history and symbolism are built into the design, and the spirit of the place. They compare it with other memorials and contrast it to Confederate monuments, which have been challenged in recent years – at least partially leading to the violent “Unite the Right” events of August 2017.

Writing for the New York Times, Pulitzer-Prize winning art critic Holland Cotter wrote in his front-page feature, published Monday, that the abstract quality of the memorial makes it an effective monument.

“With its amphitheater shape, stagelike plot of grass, and soon-evident handmadeness, it feels receptive and usable, a place for things to happen, for performances. (You’re part of one as you bend in close to read the names and stories.) Power is not its language. Closure is not its goal. Active, additive remembrance is. Is this what distinguishes a memorial from a monument? A monument says: I am truth. I am history. Full stop. A memorial says, or can say: I turn grief for the past into change for the present, and I always will.”

Located within sight of the Rotunda and the UVA Corner, and within the footprint of the UNESCO World Heritage Site, the memorial came from a design that’s intentionally symbolic. Its diameter matches that of the Rotunda, and its concentric-but-incomplete rings – made of the same granite as the Rotunda’s upper terrace – represent the shackles of slavery, broken and with a path to freedom. The innermost ring bears hundreds of known names of the enslaved, plus placeholders – or “memory marks” – for the estimated 4,000 names that have yet to be found.

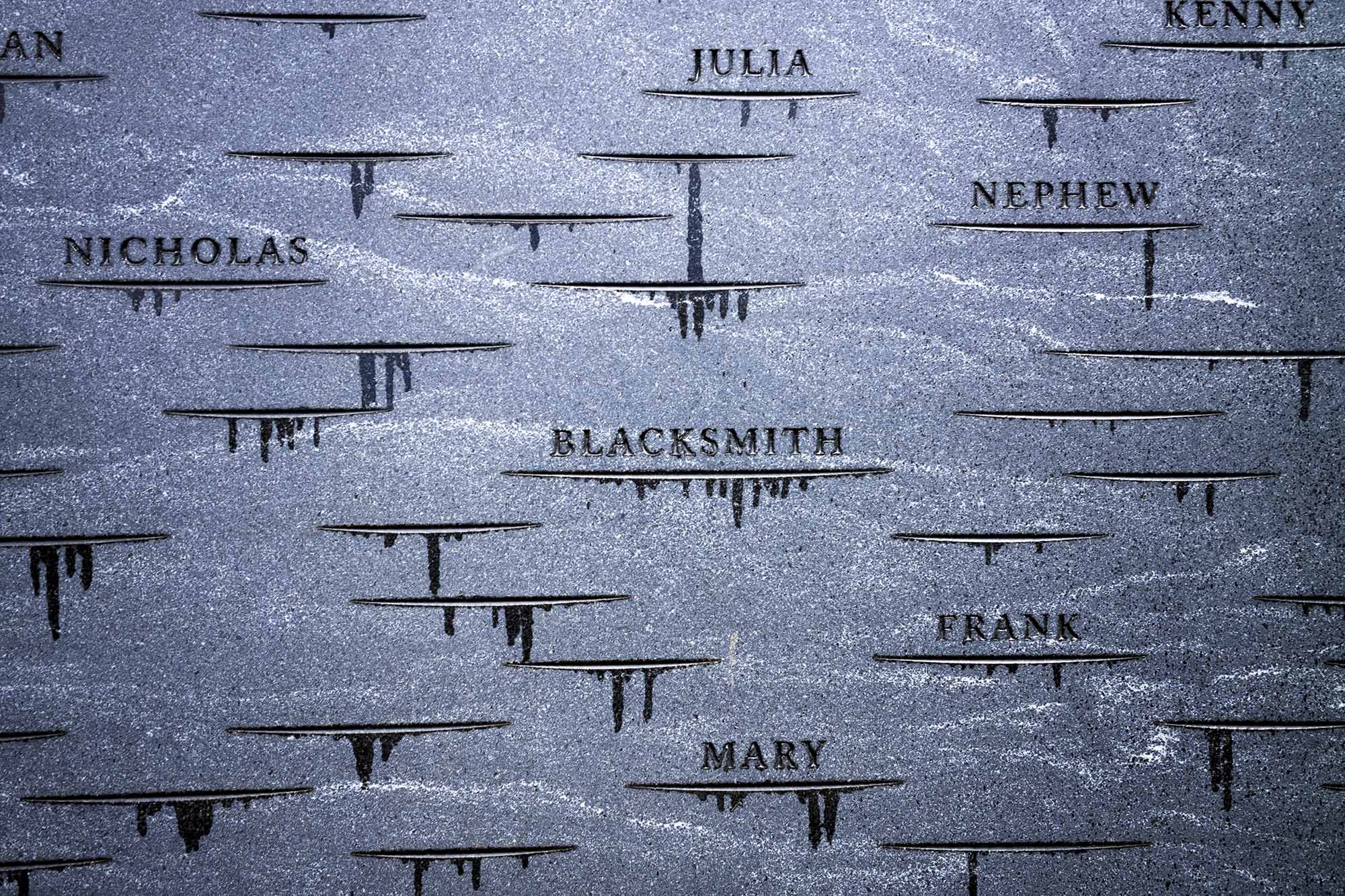

Cotter and another Pulitzer-winning art and architecture critic, Philip Kennicott, writing in an Aug. 13 Washington Post article, both noted an unexpected aspect of the design of the memory marks, short horizontal slashes in the stone. These slashes “stand in for the anonymous laborers, gashes that look a bit like wounds,” Kennicott wrote. “After a rainstorm, a visitor to the memorial noticed that water was slowly dripping from the memory marks. That visitor, a descendant of the community of enslaved laborers, told the architects this reminded her of ‘the tears of our ancestors.’”

Horizontal slashes, or “memory marks,” denote an enslaved person – by name, kinship or job, as well as the unknown. Visitors have said the rain dripping from the marks looks like tears. (Photo by Sanjay Suchak, University Communications)

Architect for the University Alice J. Raucher, who accompanied Cotter on his tour of the memorial, recently discussed the memorial at a panel of AIA Virginia, alongside Mary Hughes, landscape architect for the University; UVA alumna Mabel Wilson, a member of the memorial design team, cultural historian and designer, and a professor at Columbia University; and Meejin Yoon, whose architecture firm, Höweler+Yoon, led the memorial design team.

The professional monthly Architectural Record features the memorial on its August cover, and Raucher also describes it in an interview with another architecture-focused website, ArchDaily.

For those who are unable to visit the UVA Grounds to experience the memorial in person, a new app that provides a virtual, self-guided tour, introducing the history of enslaved African Americans at UVA, is now available. Users of the app can view beautiful aerial and ground photos with explanatory entries about bringing the memorial to fruition.

First proposed by students 10 years ago, the idea for the memorial garnered widespread support from not only UVA students, faculty, staff and administrators, but also alumni, especially through the IDEA Fund, and people from the local community. The President’s Commission on Slavery and the University pursued the idea and enlisted a range of stakeholders. In fall 2016, the Board of Visitors selected the Boston firm Höweler+Yoon to design the memorial.

The design team, in addition to Yoon and Wilson, included Frank Dukes, a community activist and past director of the Institute for Environmental Negotiation in the UVA School of Architecture; Gregg Bleam, a landscape architect who had taught at UVA; and artist Eto Otitigbe.

Media Contact

Article Information

August 17, 2020

/content/memorial-enslaved-laborers-stands-out-telling-uva-history