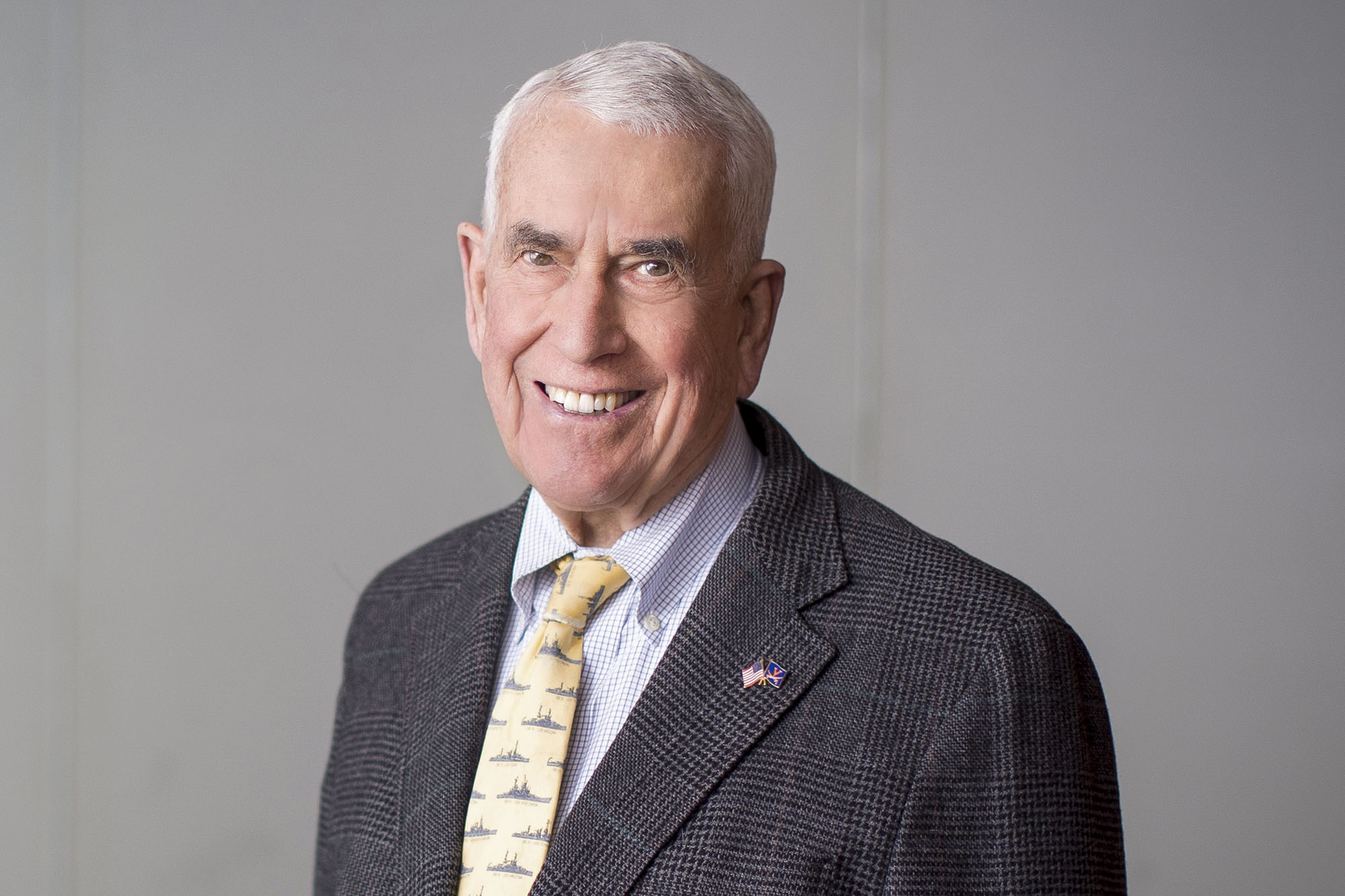

“Leigh was someone who had an idea and let others run with it,” Gibson said. “He was a quiet guy. A leader by consensus, but not by talking as much as starting things off and letting them take their natural direction.”

Fox added, “He was a person who brought people together, got lists of contacts, got funding and kept it going. He was an honest broker among a lot of different groups.”

In the interest of political comity, one of Middleditch’s many initiatives was OneVirginia2021: Virginians for Fair Redistricting. The group set out to overhaul gerrymandering in the state – a redrawing of voting districts that typically happens after a party has gained power, all done behind the scenes. Critics viewed the historical process as a way of artificially manipulating future elections, distorting how pockets of the state actually voted. OneVirginia2021’s efforts led to the successful state referendum in 2020 that established an advisory commission and new redistricting rules.

“He was the prime motivator behind the effort, which sponsored the longshot amendment,” Gibson said. “It passed with overwhelming public support and approval.”

Though the effort was not a total victory, Gibson said, because partisan appointment still plays a role in the new scheme, “It ends gerrymandering by one party through backroom dealing and introduces transparency into the process.”

Even among friends, there was some skepticism the goal could be achieved. “We didn’t think he had a chance in hell, but he did!” said Peter Arntson, a 1965 graduate of the School of Law. Arntson served with Middleditch as a trustee of the Claude T. Moore Charitable Foundation. As a major funder of health and education in the state, the foundation donated $5 million for the current School of Nursing building.

But OneVirginia2021 was typical of most of Middleditch’s projects and the way he conducted his life in general, Arntson said. “He got everybody else involved.”

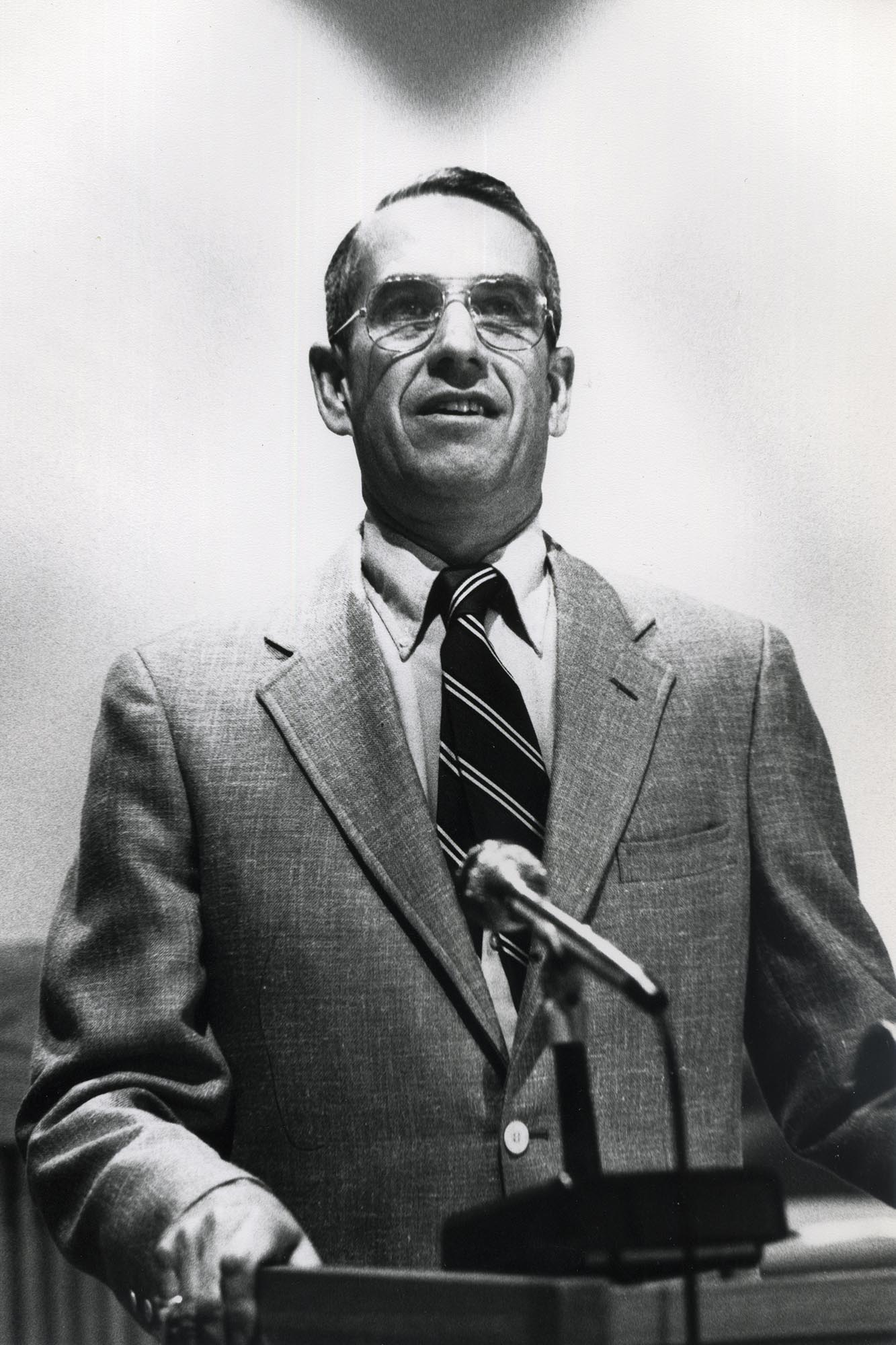

Middleditch was born Sept. 30, 1929 in Detroit. He completed his bachelor’s from UVA, where he was a member of Omnicron Delta Kappa, before embarking on naval service. He returned to the Law School through the ROTC, and passed the bar in 1957. He became an associate of James H. Michael Jr. from 1957 to ’59, then a partner at Battle, Neal, Harris, Minor & Williams from 1959 to ’68. He joined McGuire, Woods, Battle & Boothe (now McGuireWoods) in 1972.

Throughout his professional career, he was also devoted to helping UVA.

Middleditch served as the University’s legal adviser and special counsel from 1968 to 1972, during the shift to coeducation in undergraduate study. In addition to later serving on the Board of Visitors, he served as president of the Law School Alumni Association from 1979 to ’81; served on the UVA Alumni Board of Managers from 1994 to 2001, including as president from 2000 to ’01; chaired the UVA Health Services Foundation (now UVA Physicians Group) from 1988 to 1997; chaired the Virginia Health Care Foundation from 1997 to ’98; was foundation president of the Miller Center for the Study of the President; and helped start the Osher Lifelong Learning Institute at UVA in 2001.

Other major volunteering included directing the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and service on the boards of the American Bar Association, Virginia State Bar, Virginia Health Care Foundation, Virginia’s Secure Commonwealth Panel and the Virginia Council on Economic Education. He was president of the Charlottesville-Albemarle Bar Association from 1979 to ’80.

In Charlottesville, his board work included stewardship of community journalism through Charlottesville Tomorrow and indigent health care through the Charlottesville Free Clinic.

He was a former trustee for the Thomas Jefferson Foundation, which runs Monticello, and James Madison’s Montpelier.

“I don’t know that I ever saw Leigh without a sport coat, and always in the lapel was a pin with the American and Virginia flags,” UVA professor of politics James “Jim” Todd, who shared an interest with Middleditch in Montpelier, said in a Facebook post remembering his friend. “To me he was the embodiment of a good citizen and more than that a patriot who devoted a great deal of his life to working for the good of all of us.”

The co-author of the first edition of “Virginia Civil Procedure” with professor emeritus Kent Sinclair, Middleditch taught as a lecturer at UVA’s Darden School of Business from 1958 to 1990, and at the Law School for two decades starting in 1970. Those associations were how Lucius H. Bracey Jr., a 1967 law school graduate, came to know and eventually work with him at McGuireWoods. He said Middleditch strived for a more transparent and accessible law firm culture, which convinced Bracey to turn down a job he had accepted in New York.

It helped that Middleditch reached out to him personally in the hallway of the Law School.

“He mentored a lot of young people,” Bracey said.

Bracey and Fox remembered Middleditch as a serious colleague, short on words, but one who valued people.

“He always had a twinkle in his eye, which would take you off-guard. But when push came to shove, he was no-nonsense,” Bracey said. In some instances that goes along with tax work, he said, but “I think in this case the personality drove the career.”

Middleditch had taught Fox in law school. As an instructor and in social settings, Middleditch, whom Fox had known since early childhood through his father, also a McGuireWoods attorney, was reserved, Fox said. Yet he was constantly thinking of others. Middleditch wrote Fox’s son letters of encouragement every few weeks after Fox enlisted in the military. Middleditch himself had been in active duty with the U.S. Navy from 1951 to ’57, retiring as a captain in the reserve.

“He was really, in his quiet way, beloved by everyone he met,” Fox said. “He might have seemed a little gruff at times, but he really cared.”

Middleditch famously ordered lunch every day from Timberlake’s Drug Store downtown. But not just any meal, nor even any sandwich. He ordered the tuna fish sandwich. At 11:45 a.m., the women who ran the lunch counter knew to have his sandwich ready.

John Plantz, the longtime owner of Timberlake’s, said Middleditch followed this routine for decades, at least since 1977, when Plantz took over the store. From his vantage point in the pharmacy, Plantz could always see him coming, because of his recognizable gait.

“He wanted it ready for the same time every day, and he had the exact change,” Plantz said. “He didn’t want to stand around and dilly-dally.”

That meant Middleditch didn’t tip. “But at the end of the year he gave every lady at the counter a nice Christmas check.”

He would never stay to eat or chit-chat, like some of the other attorneys would.

“I think his office is the place he liked to be more than anything,” Plantz said.

Middleditch retired from McGuireWoods in 2018 after 60 years with the firm, but he rented an office downtown so he could continue his redistricting reform effort and other projects.

Although he reluctantly accepted a few awards over the course of his life, including the Sorensen Institute’s Founder’s Award in 2019, Middleditch found the work itself to be his reward, according to friends. Fox and Bracey said he instilled in his fellow lawyers that pro bono and public service were to be considered not just the occasional good deed, but a way of life.

In bringing others along, then standing behind them, “He did a lot that a lot of other people got credit for,” Fox said. The key to his lasting successes was his persistence. “If he wanted something, he was going to keep after you.”

Middleditch is survived by his wife, Betty Lou, and three children, among other family members.

Friends said that he requested that his civic contributions not be mentioned in his obituary.