With its sweeping look at one of the most tumultuous periods in American history, the PBS documentary “The Vietnam War” captivated viewers around the country when it debuted in late September. The epic 18-hour documentary series by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick takes a deep dive into the conflict with perspectives and reflections from people on all sides of the war.

Experts at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center worked as consultants on the project to ensure that those perspectives included the private musings of three American presidents.

“The production company, Florentine Films, reached out to us in 2011 to see if we could help with research in transcripts of the presidential recordings, and we thought it would be a great opportunity for us to share what we do at the Miller Center,” said Marc Selverstone, the chair of the center’s Presidential Recordings Program and an associate professor in presidential studies.

Between 1940 and 1973, six consecutive American presidents secretly taped thousands of hours of their meetings and telephone conversations. Since 1998, the Presidential Recordings Program at the Miller Center has taken these now declassified recordings and made them accessible to the public. By transcribing and annotating the White House tapes, the program has created an important repository of these first-person accounts of the American presidency.

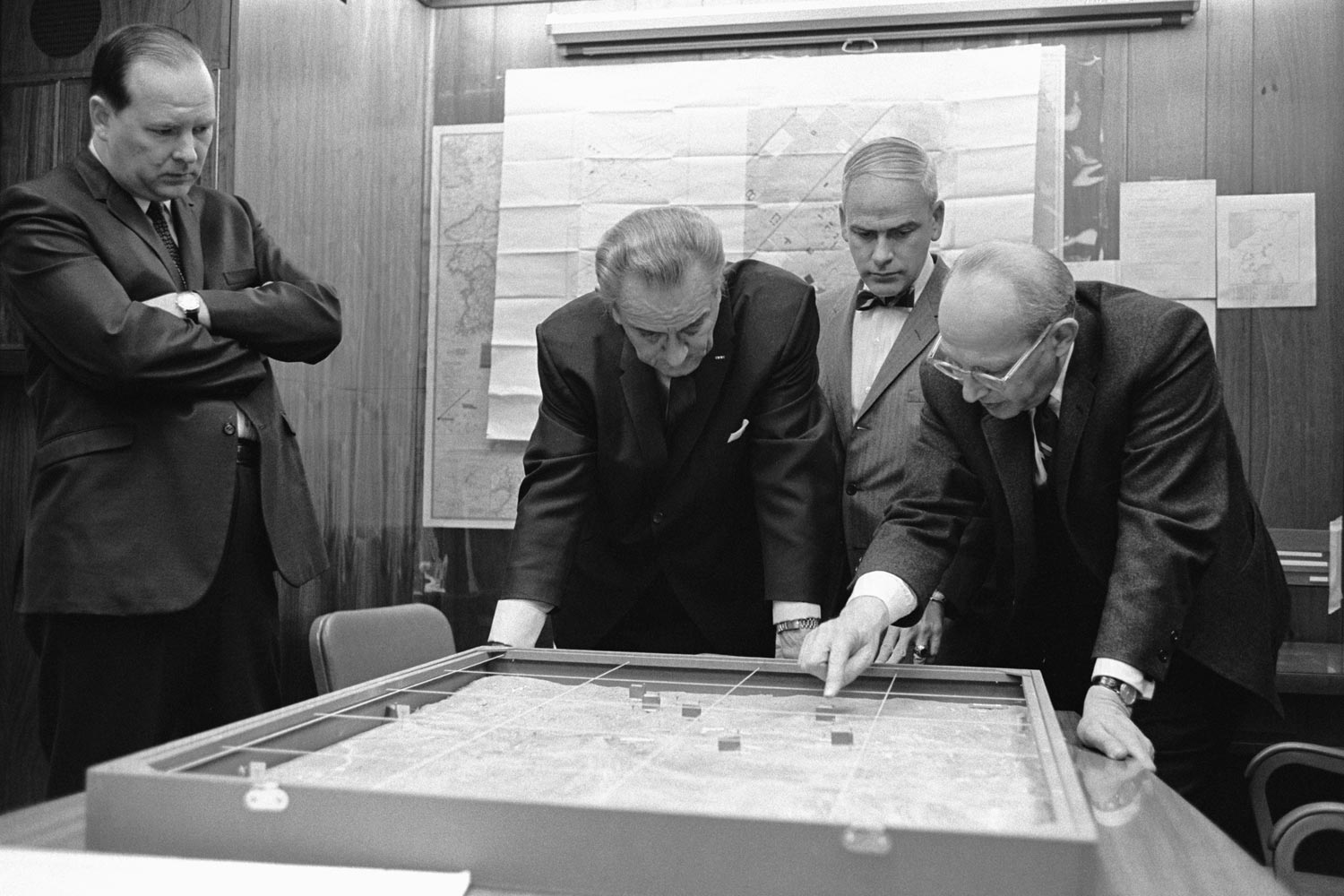

Special Assistant for National Security Affairs Walt Rostow shows President Lyndon Johnson a model of the Khe Sanh area on Feb. 15, 1968.

The Florentine Films team relied on Selverstone and Ken Hughes, a Miller Center research specialist and expert in secret presidential recordings, to help them identify the presidential transcripts of John F. Kennedy, Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon that were most relevant to the film.

With the center’s help, the production team narrowed down which presidential conversations they wanted to use in the film, bringing in each president’s own thoughts as they related to various critical moments in the conflict.

“Since the materials that we provided to them are so compelling – not just for the film, but for the country and for teachers and educators broadly, secondary school as well as college – we developed a host of companion exhibits that are now available on our website,” Selverstone said.

As viewers watch the documentary, they can turn to a new set of associated materials on the Miller Center’s website for greater background on the events depicted in the film and the presidents’ insider take on them.

“The tapes help to humanize the presidents in ways that other materials just can’t. I think it helps to make these individuals and the challenges of the office come alive,” Selverstone said. “Particularly in some of the tapes that are from LBJ, you can hear him weighing the alternatives and being fearful about going to war on the one hand, and on the other hand being fearful about not going to war given his understanding of what was at stake.”

The center’s resource page devoted to the Johnson Transition captures the president’s decision-making process over a period of months in 1964 as he is establishing his own path forward following the assassination of President Kennedy.

For Hughes, comparing this transition period with Johnson’s conversations four years later offers some of the poignant insights into the war and the growing opposition to it at home.

“I think listening to Lyndon Johnson try to untangle the incredible complexities and chaos of 1968 is gripping. There are riots and assassinations and a major offensive in the war that changes everyone’s understanding of what American involvement has yielded,” he said. “When I play people tapes from 1968, they immediately fall silent. They’re taken back into that time.”

Hughes’ own research has focused heavily on the presidency of Richard Nixon and his influence on peace negotiations both before and after he took office. The Miller Center’s supplemental materials, “The Turning Point: 1968” article and the upcoming “Vietnamization” piece, take readers behind the scenes of tension-filled calls between Johnson and Nixon and show how Nixon sought to frame the war for the American public.

“This is an opportunity for Americans to learn why Richard Nixon did what he did and why the war went on for four years throughout his first term as president,” Hughes said. “It was surprising and shocking to me that Nixon prolonged the war for political reasons, and I think it’s essential that Americans hear him in his own words as he’s making those decisions.”

Full audio files and analysis of Nixon’s conversations and those of his predecessors are available through Miller Center’s website now and will remain online as “The Vietnam War” continues to air on PBS throughout October and November.

Media Contact

Article Information

October 3, 2017

/content/miller-center-experts-aid-pbs-production-vietnam-war