Ingenuity / Kaylyn Christopher / 10.10.16

On the slopes of the Blue Ridge Mountains at Wintergreen Resort last winter, a group of teenagers participating in a weeklong ski and snowboard camp tested their abilities to maneuver through freshly fallen snow.

All of them knew firsthand the daily challenges of living with Type 1 diabetes. For many, the ski trip was the first time they were able to fully enjoy an extended stay away from home.

An hour from the resort, researchers at the University of Virginia’s Center for Diabetes Technology have spent years developing a smartphone that acts as an artificial pancreas – a device that automatically regulates blood sugar levels through customized insulin delivery. Thanks to a partnership between the center and Riding on Insulin, a program led by professional snowboarder Sean Busby that offers ski and snowboard camps for children with Type 1 diabetes, that week at Wintergreen provided the teens with a reprieve from the constant diligence required to monitor blood sugar levels – an ongoing task that so often limits their everyday lives.

“Having an artificial pancreas would mean more freedom and less worry for all of us,” said Mara Hallett, whose son, Thomas, tried out the device while attending the camp. “We have been so thankful to the doctors willing to do the research, which is bringing us closer to that reality.”

A Simpler Lifestyle

This breakthrough could make a more carefree lifestyle attainable for those with diabetes. Activities that were once troublesome for those diagnosed can be done with less worry.

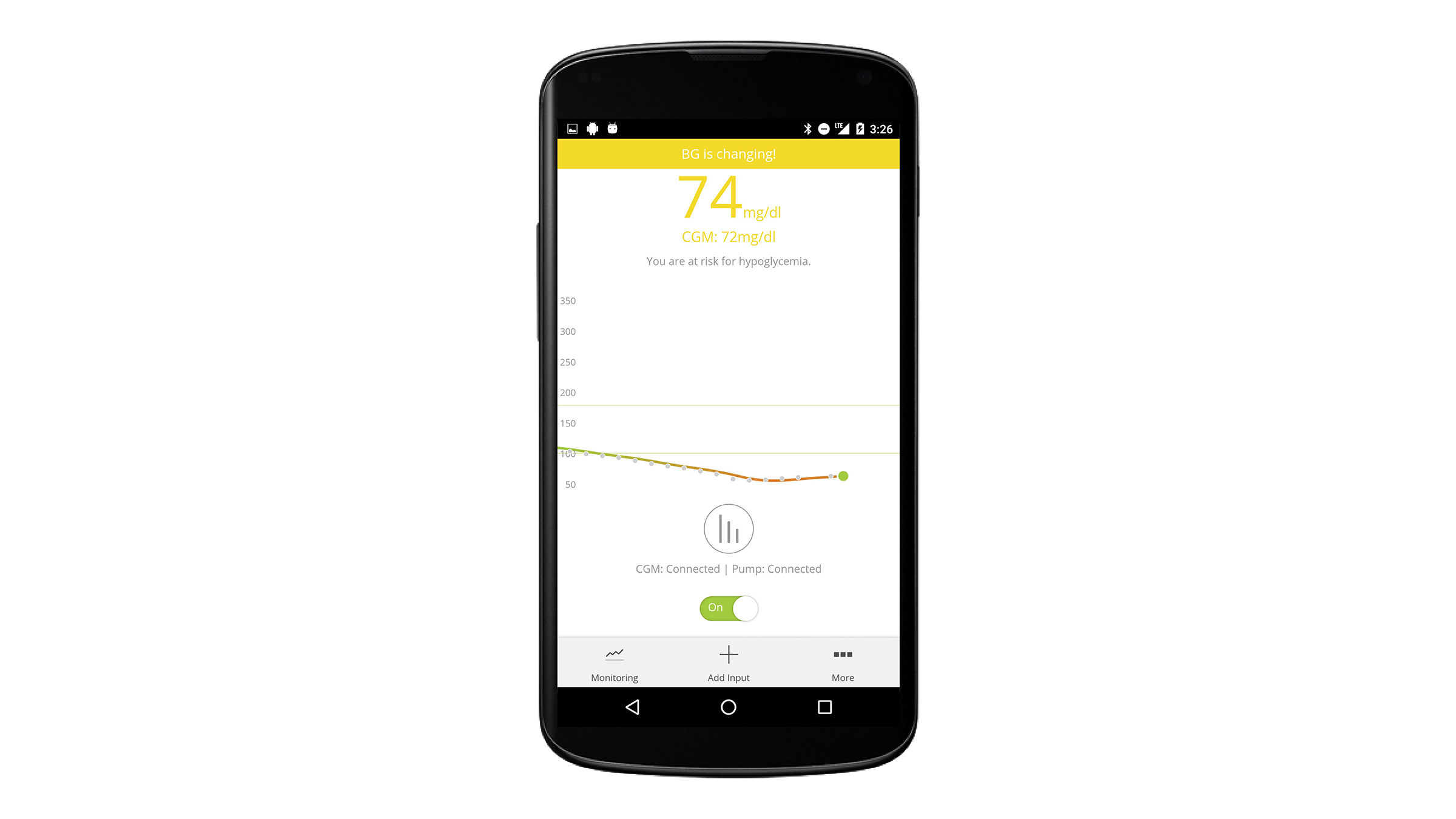

The artificial pancreas calculates how much insulin is needed after a meal.

Its mobility makes monitoring blood sugar levels during exercise possible.

Sugar levels during sleep are stabilized without disturbing the user.

Kovatchev was no stranger to the disease, having witnessed and felt the effects within his own family.

“My father had diabetes, so I knew how difficult it can be to control,” he said. “There was no technology at that time, just an occasional finger stick or insulin injection.”

A spark was ignited in Kovatchev’s mind, leading him to narrow the focus of his research to diabetes technology. Then, in 1996, he secured his first grant from the National Institutes of Health to study the mathematical, quantitative understanding of the disease. Over the next several years, Kovatchev closely communicated with colleagues at UVA and experts at the University of Padova, Italy, to brainstorm new ways to manage and monitor diabetes using mathematical algorithms.

That brainstorming culminated on Dec. 19, 2005, when the idea for the artificial pancreas was born out of a meeting between JDRF (a diabetic research foundation), the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, the NIH and experts in the field.

“Technology within the industry started to appear in the first few years of this century,” Kovatchev said. “In 2005, insulin pumps had been in use for a few years, but it became clear that it may be possible to assemble a system that could more closely control diabetes. At that time, though, no one knew whether or not it was going to work.”

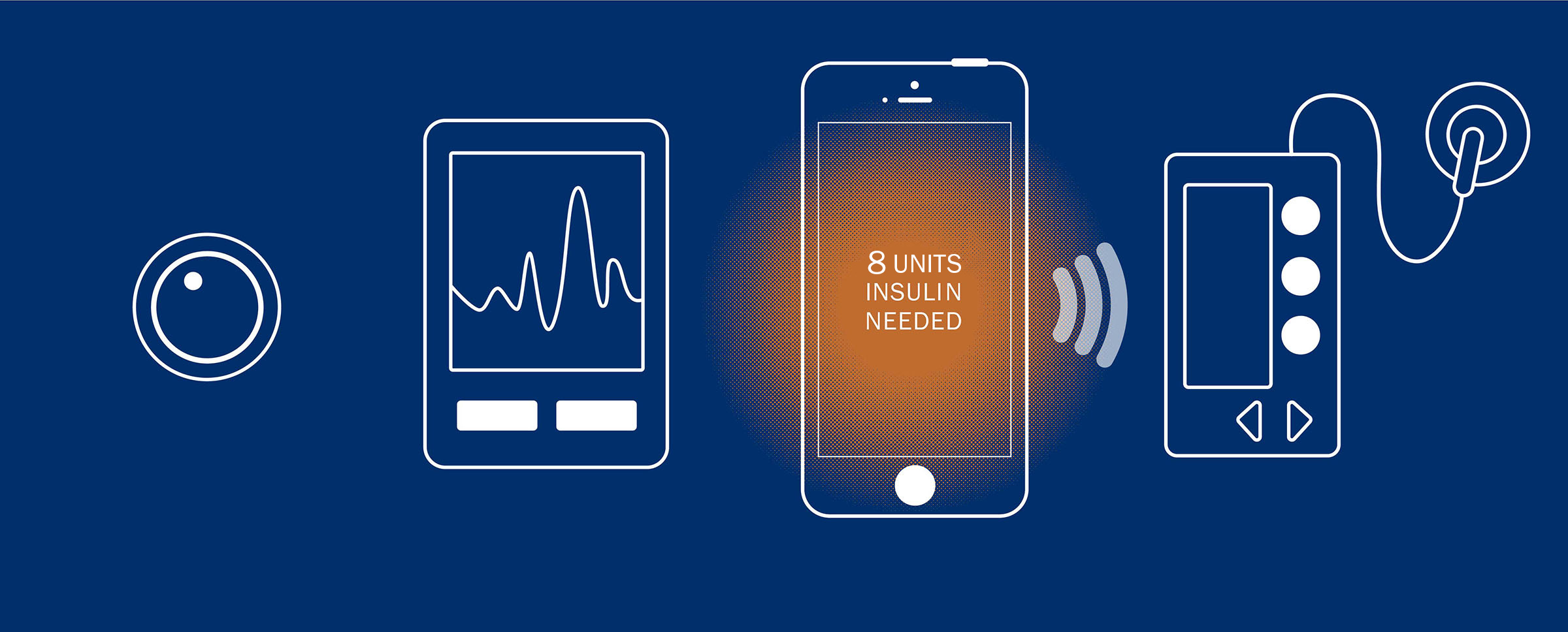

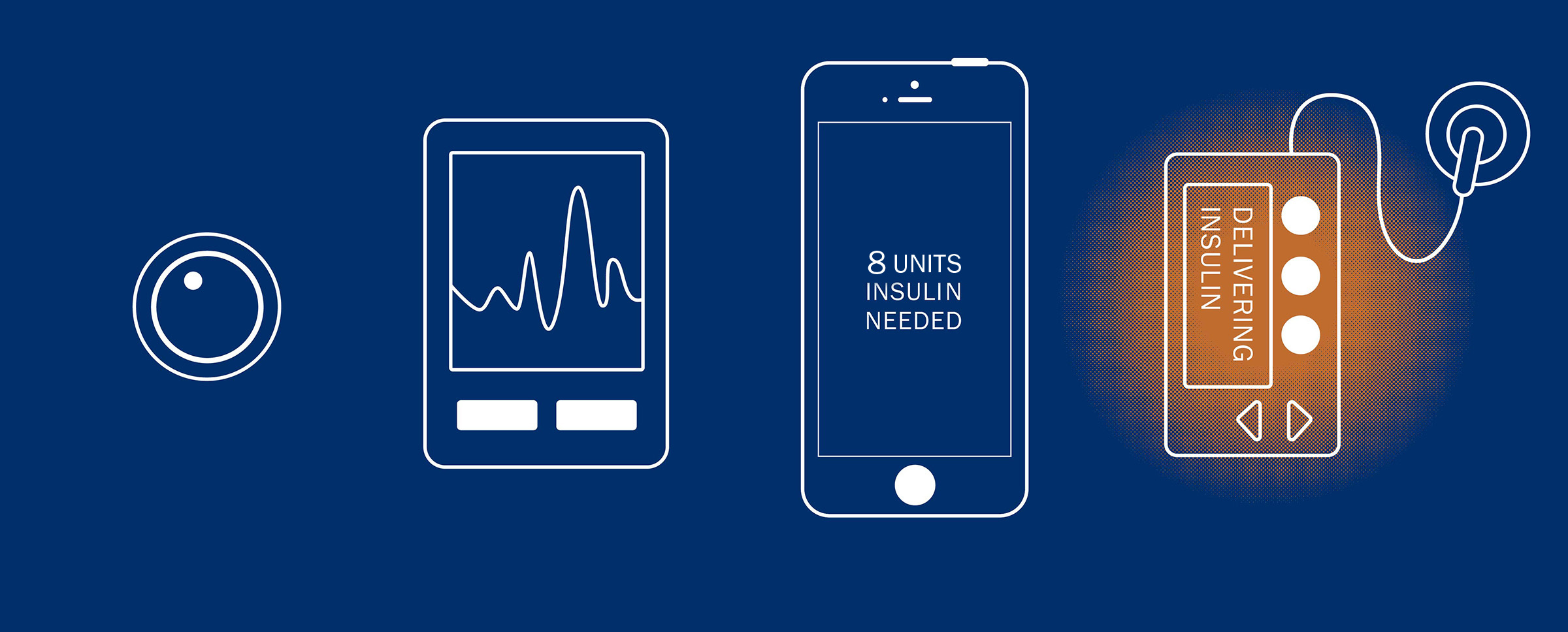

Tools such as insulin pumps help patients manage diabetes, but still require action from the individual to monitor blood glucose levels and deliver insulin dosages. The artificial pancreas, on the other hand, eliminates the need for individual action by using algorithms to automatically monitor and regulate blood glucose levels through custom, calculated insulin dosages.

Then, in 2008, Kovatchev and his team had a breakthrough. Typically, once a device like the artificial pancreas comes out of the conceptual phase, it undergoes years of animal trials. Kovatchev wasn’t keen on that idea, and instead proposed to replace animal trials with those using a computer-based simulator that modeled the human metabolic system. The FDA approved, and that same year, after the computer simulations were successful, the first human studies involving the artificial pancreas began at the UVA Health System.

“At that time, the system worked on a laptop computer and had a lot of wires connecting the sensors to the person and the insulin pump,” Kovatchev said. “It was pretty bulky.”

If we pull it off, we will essentially change the course of diabetes medicine and completely turn the treatment of it around.”

The human trials, which required participants to be closely supervised in the hospital, demonstrated significant success, and Kovatchev and his colleagues wanted to progress to outpatient studies. First, however, they needed a more mobile device.

So a member of Kovatchev’s team transferred the entire system from the laptop to a smartphone, and, over time, made it operate wirelessly.

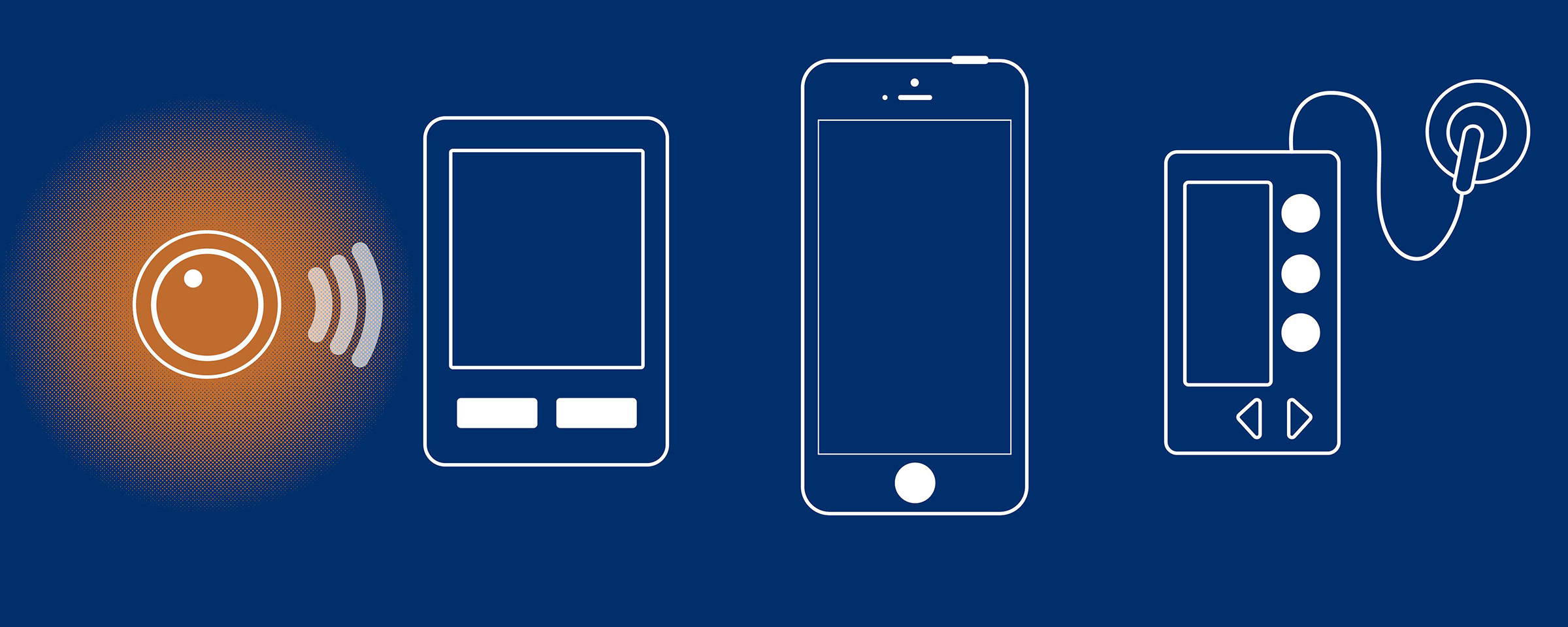

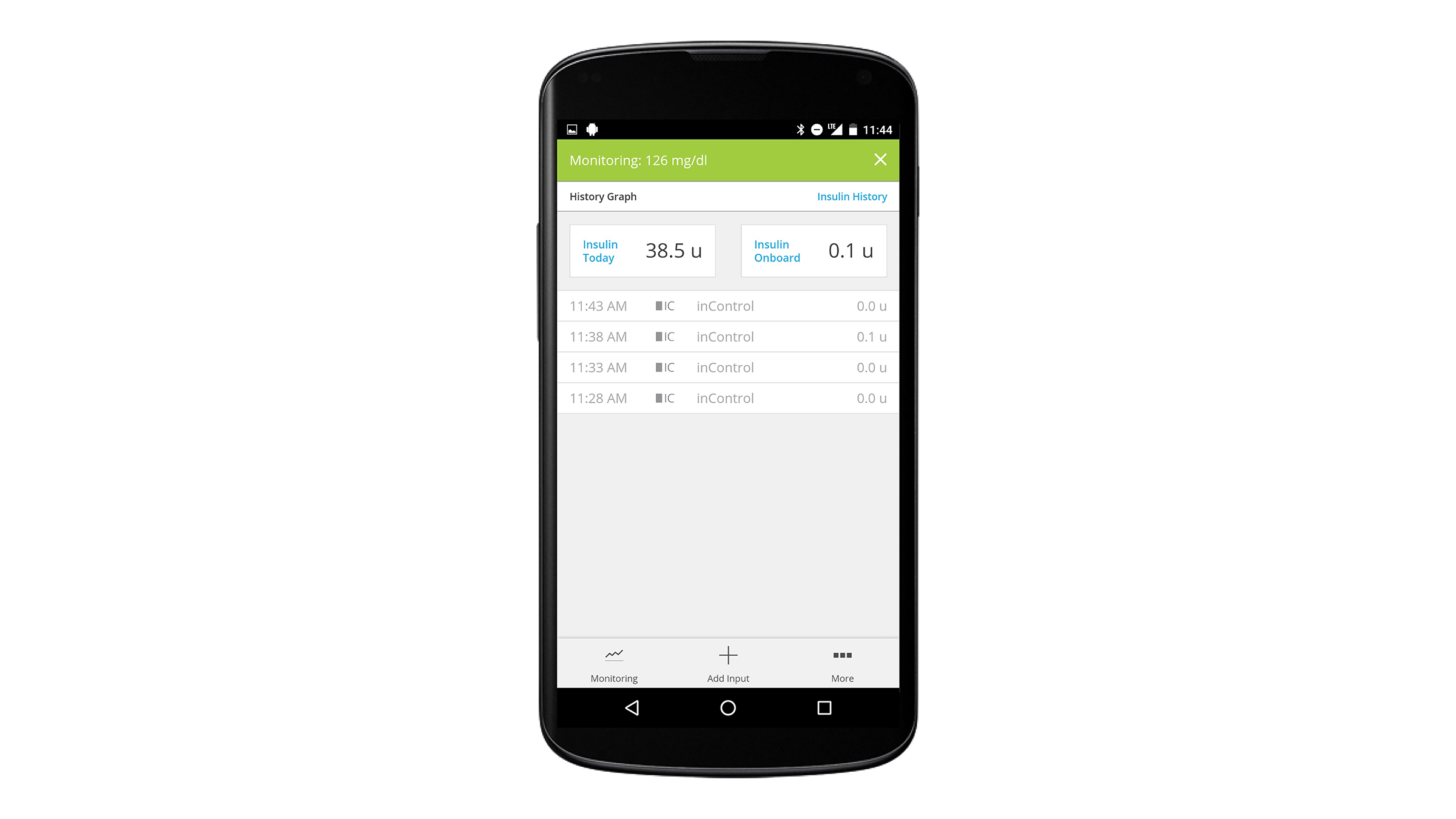

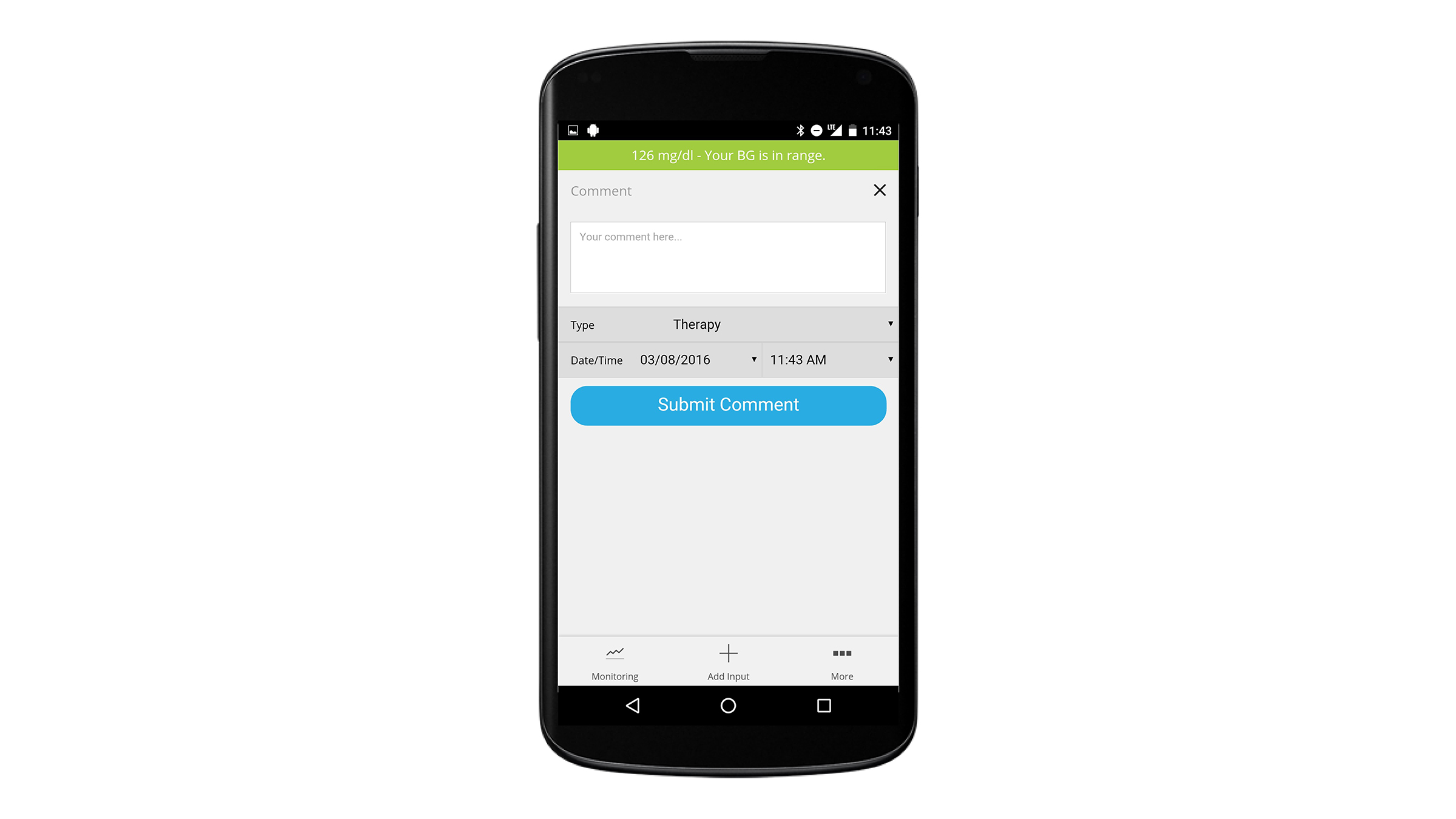

The smartphone is designed so that it “listens” to a sensor attached to the patient’s skin, and, using advanced algorithms that are linked to the sensor through wireless connections, the device gathers data from the metabolic system to then control the insulin pump so that it automatically adjusts insulin delivery.

Today, outpatient trials of the artificial pancreas have been conducted in 17 locations across the world, and the UVA Center for Diabetes Technology has become a hub for international research.

The commercialization of the device for industry use would bring 20 years of conceptual research, development and clinical trials to life.

“If we pull it off, we will essentially change the course of diabetes medicine and completely turn the treatment of it around,” Kovatchev said.

And as Kovatchev thinks back to the study at Wintergreen, he is hopeful about what the realization of the artificial pancreas could mean for kids like Thomas Hallett.

“For the kids who have diabetes, I hope this can give them much more carefree and stable lives,” he said. “The complications of diabetes are severe, and the only proven treatment is stable blood sugar control. If we can ensure that, that will lead to better, longer, healthier lives.”