John Scully and his students think about what comes out of the kitchen faucet.

Scully – who chairs the Materials Science and Engineering Department at the University of Virginia’s School of Engineering and Applied Science, and co-directs, with Robert Kelly, UVA’s Center for Electrochemical Science and Engineering – spent the summer working with undergraduate and graduate students exploring the water problems of Flint, Michigan in an effort to get some specific scientific answers.

In 2014, the city of Flint switched its water supply from Lake Huron to the Flint River as a cost-cutting measure while the city was under the state’s emergency management. The Flint River water contained higher levels of chloride, making it more corrosive than the lake water, and this caused increased lead release from the system’s old lead water pipes.

At the same time, water system managers were not treating the water using the chemical orthophosphate, as a money-saving step. In public water systems, orthophosphates are used for lead corrosion-control purposes. Orthophosphates chemically react with the lead atoms leaching from pipes into the surrounding water. The chemical and electrochemical reactions between orthophosphates and lead atoms forms lead phosphate, which is electrochemically formed on the pipe surface. Lead phosphate forms a tough, corrosion-resistant coating on the pipe, which helps prevent further lead leaching into the surrounding water.

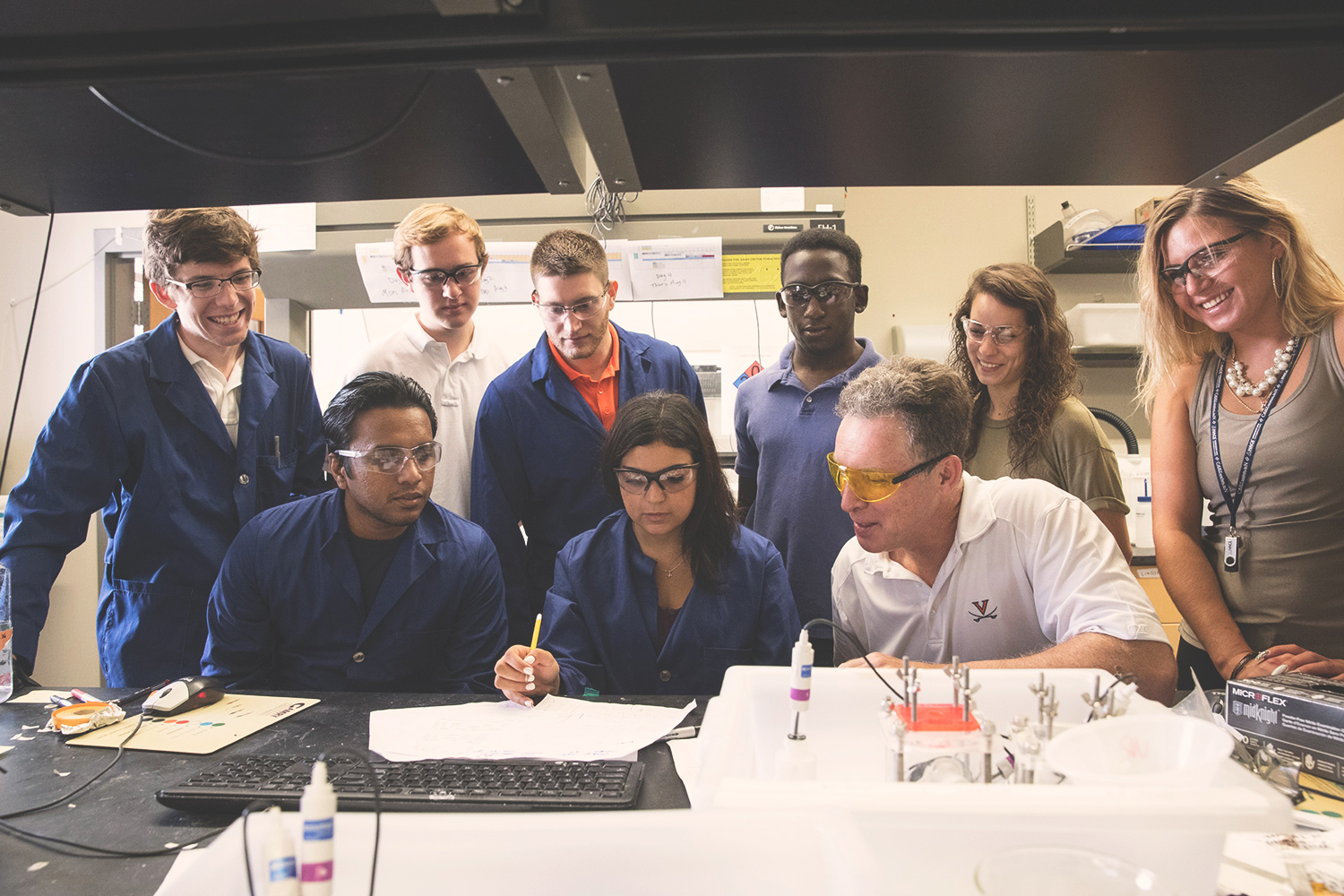

Materials science professor John Scully and students are studying the lead-pipe corrosion issue with no funding, out of concern for future water-system issues. (Photos by Dan Addison, University Communications)

Scully said his students’ research indicated that just a small amount of the orthophosphate was needed to treat the lead-leaching problem – treatment that Flint officials have resumed. Scully’s group is researching the problem with an eye toward future water system problems, since the country is dealing with an aging water infrastructure.

Lead water pipes were installed in municipal systems around the country from the early 1800s into the 1900s, with the justification that lead was more malleable and less corrosive than iron pipes and lasted longer than cast iron. People then did not understand that lead was a poison, he said.

Over time, people recognized the problems of leaching lead from the pipes and proposed ways of dealing with it, including reducing the acceptable levels of lead in the water.

“As the years went by, the allowable lead levels got lower,” Scully said, as the lead’s health risks became known.

Corrosion in water pipes and in many technological applications is often a difficult problem because it is a long time before the damage becomes evident and, because the pipes are out of sight – literally buried underground – corrosion maintenance may be deferred, creating more expensive remediation and replacement issues later.

Because of the prevalence of lead pipe, Scully said lead leaching can happen in many water systems, and is subject to changes in water chemistry that make conditions more corrosive. His students want to help mitigate the issue.

“This is a real problem that is never going to go away as long as lead pipe is in service – and it could have been avoided,” said Veronica Rafla of Boise, Idaho, a graduate student in materials science. “Before we started this, we didn’t how little phosphate was needed to solve the problem. It is shocking. A small amount can make a huge difference. A little gives an immense benefit.”

The students also researched whether orthophosphate would still work to inhibit further lead corrosion that had already begun in circumstances where it had been used and discontinued.

Jacob Wright, of East Orange, New Jersey, who graduated from UVA in May with an engineering science degree, said the research is important because of the age of much of the water infrastructure in the country.

Kateryna Gusieva, a Ukrainian post-doctoral research associate working in materials science, agrees. “Sometimes problems can be overlooked and it doesn’t take much to solve them,” she said.

Scully said that while there is a lot of old lead pipe in the national infrastructure, some of the pipe has been replaced. Still, the use of the copper replacement tubing may “accelerate the corrosion of the remaining lead sections of pipe by a process known as galvanic corrosion,” he said.

He said it was important that researchers solve these problems because the people who run the water system are not corrosion experts.

“If you don’t know something, you ask the experts,” Wright said. “But sometimes the half-solutions often implemented can create their own problems.”

This has been, and continues to be, a project of passion for Scully and his students. Scully has received no funding for the research so far and the students are moonlighting from their own research projects.

“The project will likely never end, in that we will continue in some residual or low-level way because we did this in our spare time anyway,” Scully said. “It was unfunded,. All my students are funded on something else – no one is coming in yet with exclusively dedicated lead corrosion funding.”

The students echo Scully’s dedication.

“I have been in the corrosion business for eight years and I think this is my contribution to the real world,” Gusieva said. “Growing up, I never thought I would make a difference because in my country the politics are difficult, but this work is helping people in a broader sense.”

Scully said he may apply to the National Science Foundation for funding for the lead corrosion research, to further examine issues such as what happens when an inhibitor chemical is used, discontinued and then reintroduced, but he said that might also be helpful to other situations.

“It is of no direct use at Flint as long as the restored orthophosphate treatment works and/or the water supply has been switched to a less-corrosive source, but maybe if we show that chemical treatment is inadequate once you go through a period of ‘no inhibitor use’ in a corrosive water situation, that would be a piece of information that would be worthwhile to share and might have practical impact,” Scully said. “We don’t have a complete story to make that assertion yet.”

He said the results of the students’ work, once analyzed, re-run and double-checked – “No answer is better than the wrong answer, by order of magnitude,” Scully said – may be published. He noted that the journal CORROSION, where Scully is the technical editor-in-chief, has already published and “granted free open-access status” material on lead corrosion in water pipes in an effort to get word out about the dangers and solutions.

“The research we do will be eventually reported out in an archival journal,” Scully said. “We are disseminating knowledge that hopefully trickles down to the general public for the benefit of all. It is also helpful to the students’ careers.”

Media Contact

Article Information

September 27, 2016

/content/professor-students-examine-lead-corrosion-pipes-light-flints-problem