Think back to when you were a young child. It is deep summer and you’re playing outside on a hot afternoon.

Your parents offer you two options: You and your friend can make a pretend lemonade stand and sell the pretend lemony drink for pretend money. The other option is the real deal: real, tangy lemonade and real money. Which would you choose?

The answer is pretty clear, right? You’d want to do the real thing.

Pretend play is a quintessential activity of early childhood and parents fit out toy rooms in the belief they will unleash their child’s creativity and development. But University of Virginia researchers have found youngsters overwhelmingly prefer real activities to pretend ones. What’s more, they have found little data to support the widely held notion that pretend play is a crucial element of childhood.

UVA Psychology Professor Angeline Lillard did the research with graduate student Jessica Taggart and lab coordinator Megan Heise. (Photos by Dan Addison, University Communications)

“Pretend play is absolutely fascinating. I adore it as an activity,” UVA psychology professor Angeline Lillard said. “But over the years it seemed like the research wasn’t as strong as people were giving it credit for, in terms of showing how pretending might help development, so we did a big review and really ended up quite discouraged about the state of the evidence there.”

Lillard, graduate student Jessica Taggart, and lab coordinator Megan Heise decided to dig deeper to see what young children would do, given the choice between pretending and doing real activities.

Methods

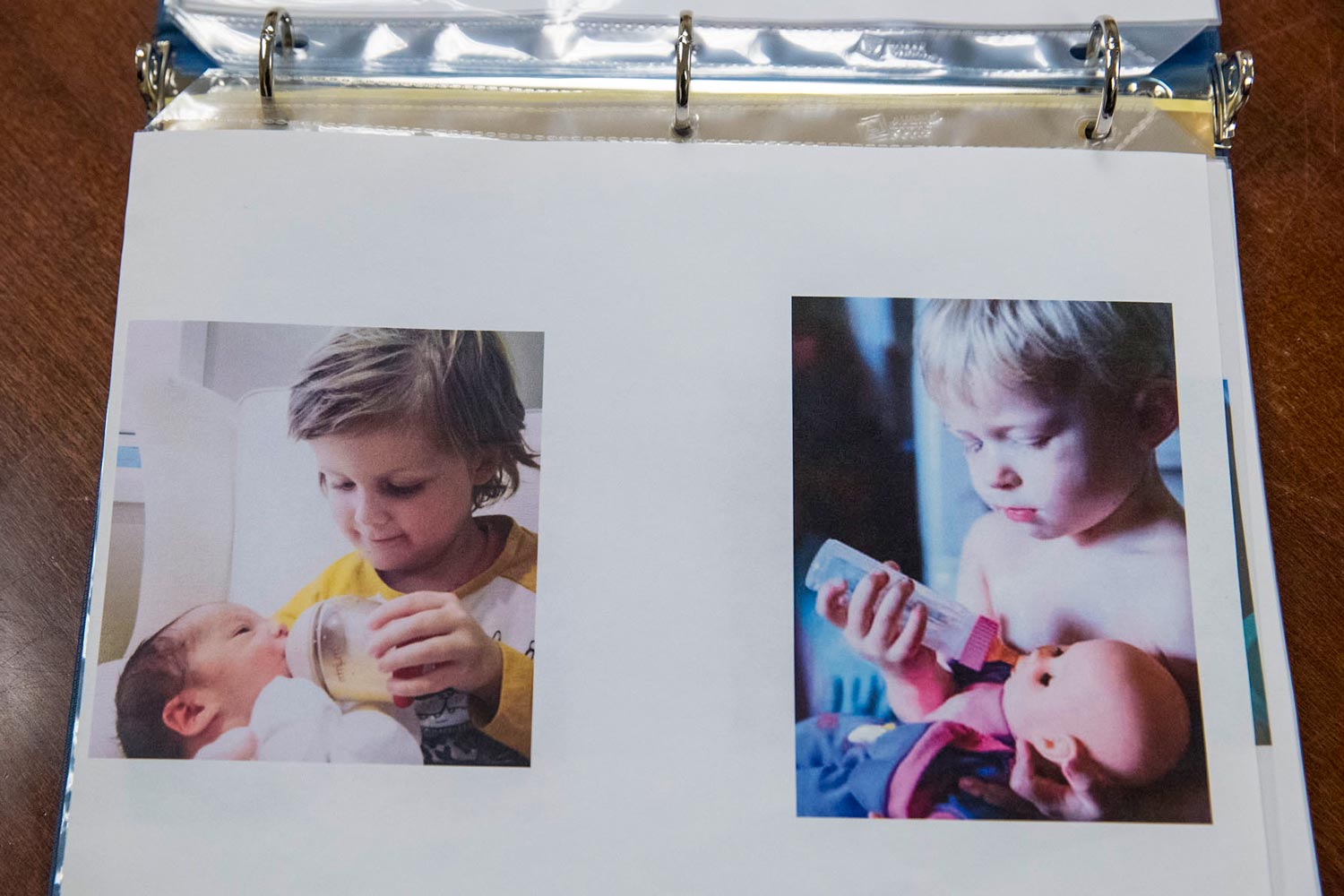

The trio of researchers presented 100 middle-class children, aged 3 through 6, with nine different scenarios. Would they rather pretend to bake cookies or really bake cookies? Would they rather pretend to go fishing or really go fishing? Would they like to pretend to feed a baby doll or really feed a baby?

Young children in the study were shown pictures of two examples of an activity and asked to choose their favorite. In this example, they voiced a strong preference for feeding a real baby, as opposed to pretending to feed a doll.

“What we found was that children overwhelmingly chose the real option,” Taggart said. “They picked pretend for only one of nine activities.”

The preference for real activities increased from age 3 to age 4, then remained steady through age 6.

Why is this distinction important? “I’m really interested in how children choose to spend their time when they are the ones getting to choose how that time is spent,” Heise said.

“I think one of the big questions is, if we have this attitude toward pretend play in the United States ─ that it is important, and children should be actively engaged in it ─ is it something they are actually motivated to do on their own? Or is it something we are showing them to do? [We’re] really getting down to what children want to spend their time doing rather than just presenting them with the activities that we think are appropriate.”

Lillard said real activities also give children a sense of accomplishment.

“There is this issue of self-efficacy – What is helping a child to feel like they have a role in the world, that they can do something in the world?” she asked. “If we always relegate them to the pretend kitchen and the pretend things, we aren’t giving them the opportunity to experience doing things for real, and that might really do a lot for a child.

Asked to choose between cutting toy vegetables and real vegetables, the preference was clear. Young children wanted to do the real activity.

“In fact, the children told us that the reason they wanted to do things for real was because they wanted to accomplish things. And when they said they wanted to pretend, it was usually because they were afraid of doing the real thing – they felt they weren’t able to do the real.”

Lillard said one father to whom the study was described balked at the notion and said “Kids just don’t know what’s good for them.”

“I think it’s important for parents to get the message children are sending here. Think about it: If you have this choice, if you have the time and the ability to help your children do it for real, the real experience might really be meaningful for them.”

And it’s not all just fun and games. In the group’s paper on the research, just published in the journal Developmental Science, they write that in 2016, more than $20 billion was spent on children’s toys.

“The toy industry is less than 100 years old and arose in tandem with the notion that play is ‘essential for development,’ an idea endorsed by middle-class American parents and the American Academy of Pediatrics,” reads the introduction of the paper.

RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS

- When given a choice, preschool-age children overwhelmingly preferred real activities to their pretend equivalents.

- Children’s preference for real activities appeared between 3 and 4 years of age, then was constant through age 6.

- Children said they preferred real activities because they are functional, useful and provide novel experiences.

- When children preferred pretend activities, the most-cited reasons were being afraid of the real thing, lack of ability, and lack of permission.

Lillard said all this pretend play crowds out doing real activities. “Montessori [education] is an exception to that that – it’s all real stuff and there’s not pretend stuff” in the classrooms, she said.

But when you walk into people’s homes and playrooms, they are usually set up with lots of toys and things to play with. “But how often are children invited to come in and help prepare [food in the] kitchen? How often are the children being taught how to clean their own room and how to clean the bathroom and things that they are able to do and they would get some sort of self-efficacy from doing?”

Still, the notion of pretend play is deeply entrenched in American society. “We are excessive in our toys,” Lillard said. “In other countries, they don’t have whole play rooms and all these things. We go overboard.”

Media Contact

Article Information

August 23, 2017

/content/put-aside-those-toys-your-kids-want-real-deal