Yevgeny V. Prigozhin, who was head of the mercenary Wagner Group that fought on behalf of Russia in its war with Ukraine, then led an ill-fated rebellion against Russian leader Vladimir Putin in June, is among the dead after a civilian aircraft crash last week.

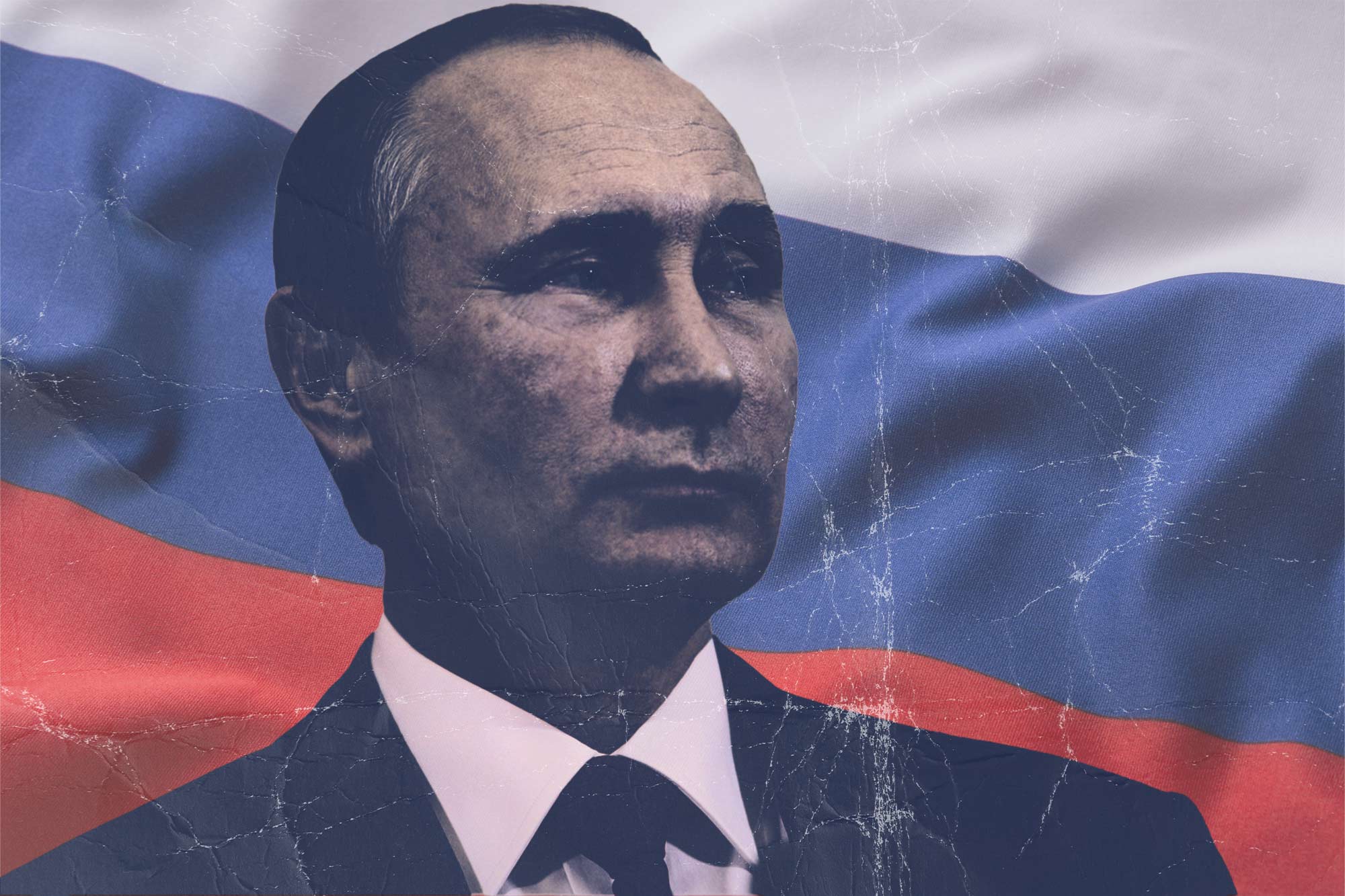

While neither Russia nor Putin claimed they caused the crash, a number of foreign affairs experts say this has the earmarks of a classic Russian reprisal.

To learn more, UVA Today talked with Paul B. Stephan, a senior fellow at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center of Public Affairs and the John C. Jeffries Jr. Distinguished Professor of Law at the UVA School of Law. Stephan is an expert on international dispute resolution and comparative law, with an emphasis on Soviet and post-Soviet legal systems. His current research focuses on the legal issues related to the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Q. Why is it a reasonable assumption that this was not accidental?

A. The expressive value of his death was too important to the powers-that-be. We have reports of witnesses who heard an explosion. An accident can never be ruled out, but this happened on the two-month anniversary of Prigozhin’s march on Moscow, the day after there is an official statement on the reassignment of the general who was thought to be a principal Prigozhin backer within the regular military. The general pattern, not just with Putin, but historically, is you aren’t fit to be the leader if you can’t dispose of your enemies in an expressive way. There’s no proof, but the circumstances suggest that it’s more likely than not.