Dimorphos’ gravitational attraction to Didymos made it a safe asteroid to poke for testing purposes. The DART spacecraft, about 100 times smaller, only needed to alter the moonlet’s orbital energy by a relative fraction with the impact in order to change its overall trajectory.

Although it may take a week or two to get final data, Pryal shared his early observations with UVA Today about how it all played out and what it means for NASA’s future.

Q. What were your impressions while watching the mission?

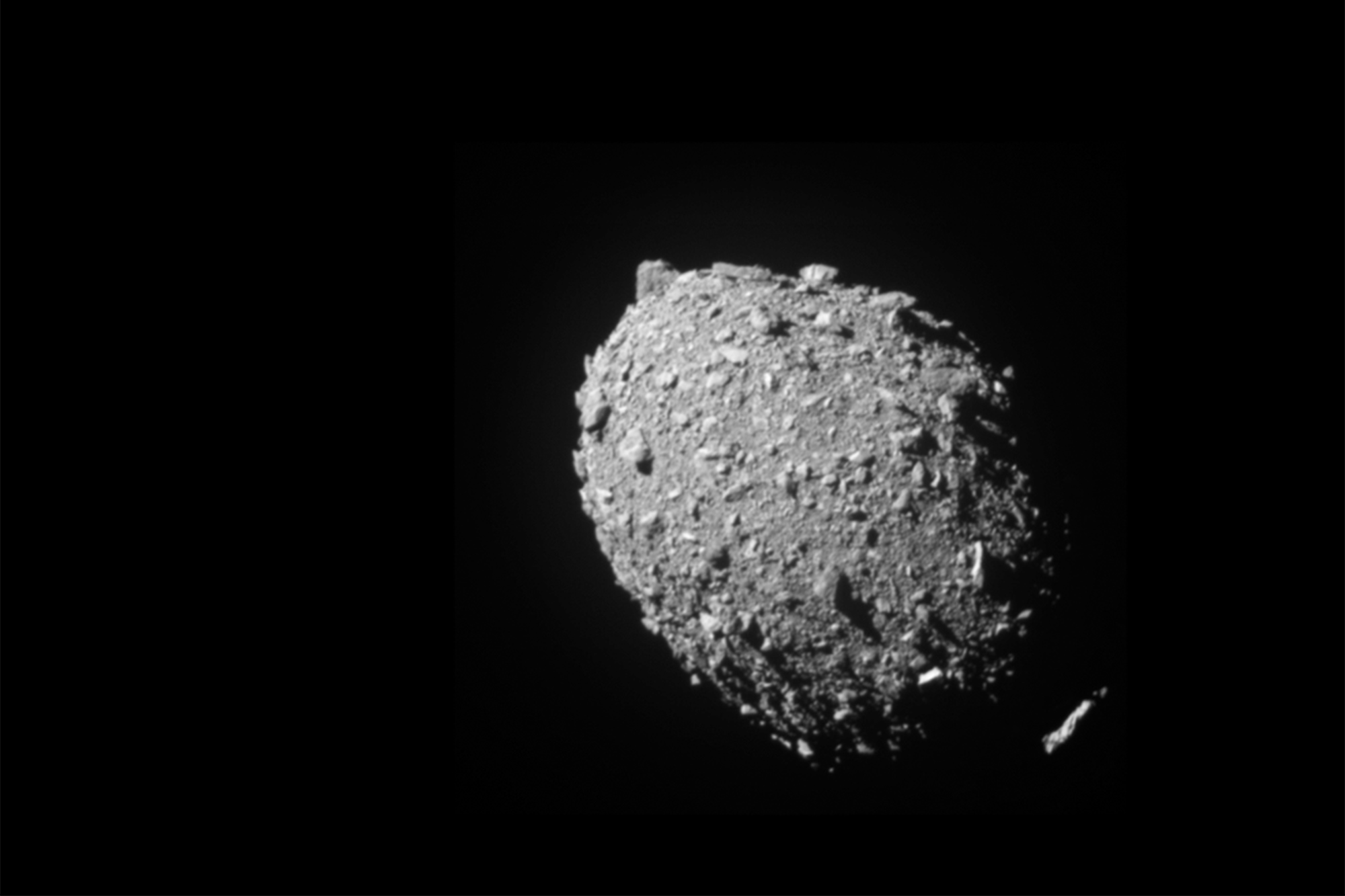

A. I was absolutely blown away over the course of the hour of the NASA livestream watching the single pixel of light that was the Didymos-Dimorphos system slowly grow in size and detail. I think many of the spectacular images we have of the universe distort our perspective of just how much innovation and hard work goes into creating those pictures, and the final images before DART’s impact with Dimorphos really resonated with me. Seeing the gorgeous phases of both asteroids, just like phases on the moon, and then finally the individual rocks on the surface of Dimorphos right before impact – the images were jaw-dropping. With current technology, those are details we can really only see with missions that actually travel to the object they’re observing (such as landers on the moon, Mars or Venus).

Q. What has impressed you most about this ambitious mission?

A. Again it’s vital to put into perspective just how hard it was for this mission to succeed. These asteroids are over 6 million miles from Earth, traveling thousands of miles per hour with respect to Earth, and we had to impact a football stadium-sized object traveling in the other direction.

I did some quick math and it’s the equivalent of hitting a golf ball so perfectly on a standard sized par-3 such that it lands on a point smaller than the width of a human hair. And keep in mind the target is moving!

The ability to show that we can do this with our modern technology is absolutely the most impressive part of this mission, but it highlights just how powerful the process of scientific advancement is.

Q. Based on the success, what are the implications moving forward?

A. Now we need to comb through the data and determine just how significantly we altered the orbit of the asteroid. This kinetic impactor method (i.e., hitting an asteroid with another object) is just one of three major ways proposed for deflecting asteroids. The other major deflection methods involve using a satellite to gravitationally attract and alter an asteroid's orbit, and using lasers to vaporize rocks on the surface of the asteroid, such that resulting jets push the asteroid off course.

Since DART is the first deflection mission to be carried out, it’s vital to see how much work needs to be done to deflect larger asteroids that can potentially be a threat to the Earth. If this deflection turns out to be as predicted, then other methods can be scaled up to alter much larger asteroids, should we ever need to do so.

Q. How likely is it that an asteroid would pose a threat to the Earth?

A. Mass extinction-causing asteroid impacts are extremely rare and happen on the order of about once every 100 million to 1 billion years. But impacts that could cause widespread devastation over the area they impact could occur every 100,000 to 1 million years. While that number may seem large compared to the lifetime of a human, it does not mean it’s impossible, and it does mean it’s happened a couple times since humans have existed.

Moreover, for the first time in Earth’s history, creatures exist on it that are technologically capable of preventing that mass extinction. I think existential, planet-destroying threats such as an asteroid impact are absolutely worth the less than 1% of NASA funding that planetary defense currently gets.

If the dinosaurs’ leading scientists were still around today, I’m sure they would agree.