Over the past few weeks, a new word has entered the shorthand we’ve used to make sense of the COVID-19 pandemic: “Delta.”

It’s an unwelcome addition. The Delta variant of the COVID-19 virus, formally known as B.1.617.2, was first detected in India and since has spread to more than 80 countries, gaining particular strength in the United Kingdom, where it is now the predominant strain of COVID-19.

In the U.S., the Delta variant accounted for about 10% of COVID-19 cases as of June 5, though some estimates now range as high as 30%. The Centers for Disease Control has declared it a “variant of concern,” meaning it is more transmissible and more likely to cause severe disease than other variants, and CDC Director Dr. Rochelle Walensky told “Good Morning America” she expects Delta to become the dominant U.S. COVID-19 strain in one or two months.

We asked Dr. William Petri to analyze the risks posed by the Delta variant and the protection afforded by the COVID-19 vaccines currently available. Petri is a chaired professor of infectious diseases and international health at the University of Virginia and vice chair for research in the Department of Medicine. His lab has been studying the effects of COVID-19 on the immune system for more than a year, seeking new treatments and researching vaccine possibilities.

For more than a year, Dr. William Petri has been studying the effects of COVID-19 on the immune system and possible treatments and vaccines. (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

Here’s what he has to say about the Delta variant.

Q. What do we know about the Delta variant?

A. The World Health Organization recently began designating variants using Greek letters. For example, the variant that came out of the U.K. this spring is the Alpha variant; the variant out of South Africa is the Beta variant. The Delta variant that we are seeing now originated in India and has spread to more than 80 countries.

We know that the Delta variant is more transmissible because it basically replaced the Alpha variant in the U.K, which was itself more contagious than the original virus. Almost every infection in the U.K. right now is through the Delta variant, which is why they have been slower to open things up.

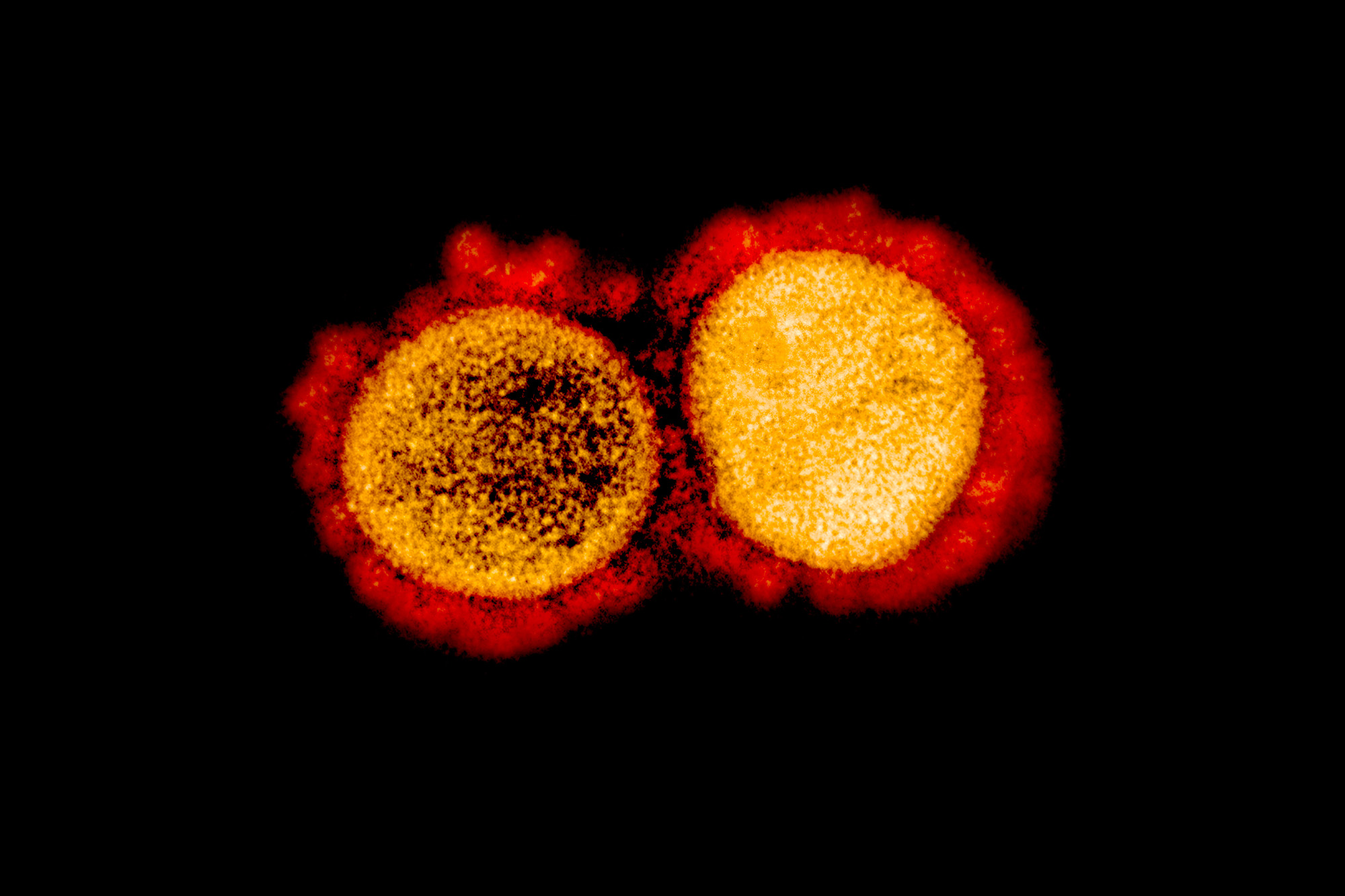

These variants tend to emerge because the virus faces evolutionary pressure and mutates. The mutations that are most successful at binding to human cells are selected through evolution and become more dominant variants. The Delta variant appears to have multiple mutations throughout the virus’ genome, and in particular several mutations in the spike protein, which binds the virus to human receptors. This variant is particularly efficient at binding to the human receptors, which is why it is more transmissible.

It is difficult to show rigorously that the Delta variant is more deadly, but we do know from the U.K. that it outcompetes the Alpha variant, which is the dominant strain in the U.S. right now. I expect we will see a similar growth pattern here.

Q. What risks does the Delta variant pose to those who have been vaccinated, and those who have not?

A. The risk is really among unvaccinated individuals. The mRNA vaccines (made by Pfizer and Moderna) appear to protect quite well against the Delta variant and particularly against hospitalization. Data I have seen from England, which is pre-publication, shows that the Pfizer vaccine was 94% protective against hospitalization. The AstraZeneca vaccine, which is an adenovirus-based vaccine similar to the Johnson & Johnson vaccine in the U.S., was about 92% protective against hospitalization. That is great news.