After a hectic election year in 2020, the University of Virginia Center for Politics and the staff of Sabato’s Crystal Ball, the center’s political analysis newsletter edited by professor Larry J. Sabato, aren’t slowing down. Instead, they recently chose to take on one of the most fraught topics in American politics: redistricting.

Kyle Kondik, managing editor of Sabato’s Crystal Ball, along with Crystal Ball Associate Editor J. Miles Coleman recently published a multi-part series on the subject.

Kondik is so interested in the topic that he wrote a book that explores how redistricting and other political trends have resulted in a Republican edge in the House of Representatives. “The Long Red Thread,” which looks at House elections from 1964 to 2020, will be released in October.

UVA Today caught up with Kondik to learn more about the controversial topic of redistricting.

Q. What is redistricting and why should people care?

A. Congressional redistricting is a vital and politically charged issue. Every 10 years, the U.S. Census Bureau releases a new census, which documents population growth patterns across the country. In order to reflect the new census, states must redraw their district lines. So between years that end in zero and years that end in two, the congressional map is reshaped across nearly the entire country – the only states that are unaffected are the six sparsely populated ones that only have a single, at-large statewide member of the House (Alaska, Delaware, North Dakota, South Dakota, Vermont, and Wyoming).

Kyle Kondik’s new book, “The Long Red Thread,” explores how redistricting and other political trends led to a GOP edge in the House of Representatives.

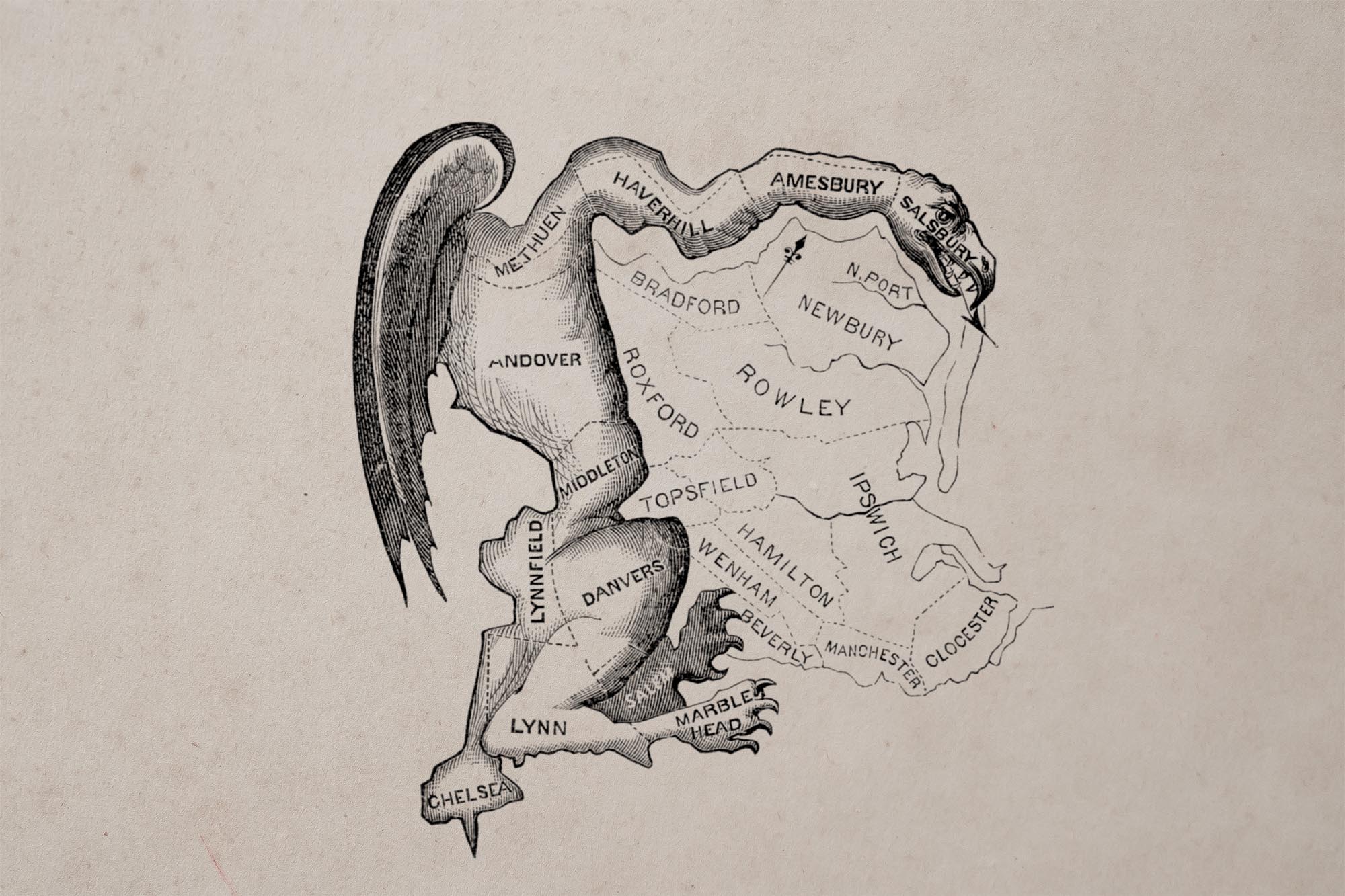

Districts must have roughly equal populations within states, with the average, “ideal” population size for a district nationally coming in at roughly 750,000 to 800,000 people. Stringent population equality requirements are a relatively new development in American politics – they only truly came about following a series of landmark Supreme Court decisions in the early 1960s, which enshrined the concept of “one person, one vote” into redistricting law. While the U.S. Supreme Court has weighed in on population equality, it has thus far declined to rule against partisan redistricting, better known as gerrymandering, which is the practice of one party drawing a congressional map designed to maximize their share of seats in a given state.

How districts are drawn has a direct impact on which party wins and which party loses a given seat. So if you care about who controls the House, you should care about this process.

Q. Who is in charge of it and when does it happen?

A. States use a variety of methods to draw district lines. Most states still use a traditional process for redistricting, which involves the state legislature proposing and passing a congressional map as a piece of legislation, subject to veto by the governor. There are variations on this process – just to cite a few examples, North Carolina’s governor cannot veto a congressional map, and Iowa uses a process in which legislative staffers draw a map that the state legislature has the power to overrule – but this is how most states handle redistricting. However, there has been a growing trend in which redistricting power is outsourced to an independent commission, which is designed to make the process less partisan. These commissions are most popular in the west, but they have recently been adopted in other places, too, such as in Virginia for this decade’s redistricting cycle.

Overall, and based on the Crystal Ball’s assessment, Republicans control the drawing of 187 districts and Democrats control the drawing of 75. Commissions will draw 121 districts, while control of government is divided in states that hold another 46 districts. And the final six districts are in the single-district states.

.jpg)