While most students last week were studying late for final exams, 32 University of Virginia engineering students were staying up late for a different reason: They were testing miniature cars in preparation for an autonomous vehicle race that was their final exam.

The students were in computer science professor Madhur Behl’s special topics class in F1/10 Autonomous Racing, combining computer science with systems engineering using 1/10th scale model Formula 1 cars.

During the semester, Behl’s students built, drove and ultimately raced the autonomous cars while learning about the principles of perception, planning and control for self-driving vehicles. They learned to use the same hardware and algorithms employed in full-size autonomous cars being developed by the automotive industry.

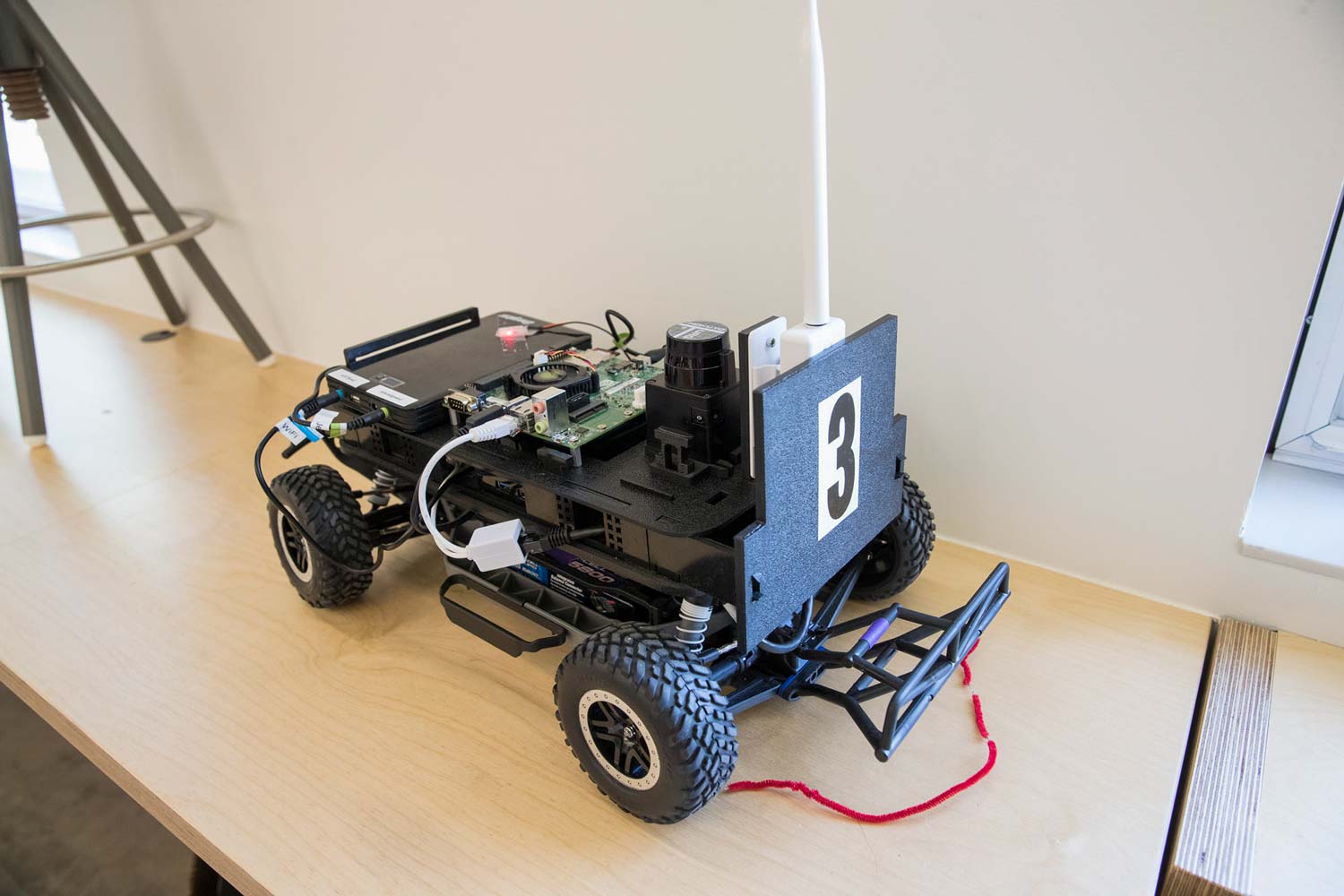

A 1/10th scale Formula 1 autonomous car, used in Madur Behl’s class.

“I love cars and computer science, and this course allowed me to work on and learn about the two things I’m passionate about,” said Arman Lokhandwala, a third-year computer science student, shortly after his team raced its car in a timed trial. “Getting to build and race an autonomous car was something I dreamed of that became a reality.”

As he spoke, a competing team’s autonomous car was whirring around a portable race track set up in the “arena” of UVA School of Engineering and Applied Science’s Link Lab, a new $4.8 million, 17,000-square-foot facility where researchers and students from a range of disciplines connect to work on engineering problems.

Eight teams ran fully autonomous F1/10 cars, under timing, in sequence, in the race dubbed by Behl as “The Battle of Algorithms.” All teams built cars using similar hardware, so the way to race faster was to outsmart the other autonomous drivers through better algorithm design – the path-planning, steering and acceleration control calculations programmed by the students into the software aboard their cars. The goal for each four-member team was to successfully, and quickly, run their cars in laps around the track without crashing. When constructed and programmed competently, the cars use a range of sensors and cameras to detect the surroundings and navigate safely while making turns that follow the course.

Some of Behl’s students likely will go on to careers in autonomous car development, which is considered the wave of the relatively near future by many in the automotive industry, with two dozen companies around the world actively doing research and development. The work involves programming and “machine learning” – training cars to learn a sense of space and to “behave,” so to speak, appropriately in the range of scenarios that human drivers face daily on highways and roads.

“I took this class because I wanted to work with something tangible, the race car, and do programming with real-world applicability,” said Allison Babick, a fourth-year computer science student who will graduate this week and work in industry. “This is a very valuable course for students who want to work on a project that can translate to industry.”

That is exactly her professor’s objective.

“Students graduating from college are expected to solve 21st-century problems involving artificial intelligence and autonomy that have not even been imagined yet,” Behl said. “This is why my teaching mirrors my own interdisciplinary approach to research.”

Behl said his course – which brings autonomy and autonomous vehicles from the lab to the classroom – is one of the first of its kind in the nation. His students learned to use the Robot Operating System, a program that runs algorithms for collecting data from “perception” sensors on a vehicle, planning the route the car follows and issuing commands for steering and braking – the same system currently used by companies on full-sized self-driving cars. The perception sensors include multiple cameras, laser range finders called LIDARs, radar, GPS and others.

“The students became experts at using and programming with the Robot Operating System through simulation exercises during the course,” Behl said, “and then, as teams, they assembled the cars by themselves, learned to work with high-performing GPUs [a computer processing chip for graphics display], and learned to work with the LIDAR range-finding sensor.”

His course material is free and open-sourced (available at f1tenth.org), and used, he said, by dozens of universities around the world to build 1/10 autonomous cars.

“Madhur’s class gives students an opportunity to get the next generation of algorithms working and to experience what technology is like in the real world, while still in class,” Travis Hite, program director for the Link Lab, said. “This is a great use of our facility, combining innovation with education, exactly as we intend, in a collaborative and energetic atmosphere.”

Media Contact

Article Information

May 14, 2018

/content/racing-students-unique-course-put-self-driving-cars-final-test