Road trips are a quintessential part of summer – why not learn something along the way? University of Virginia School of Law professors created this trek to visit landmarks in law in Virginia and Washington, D.C.

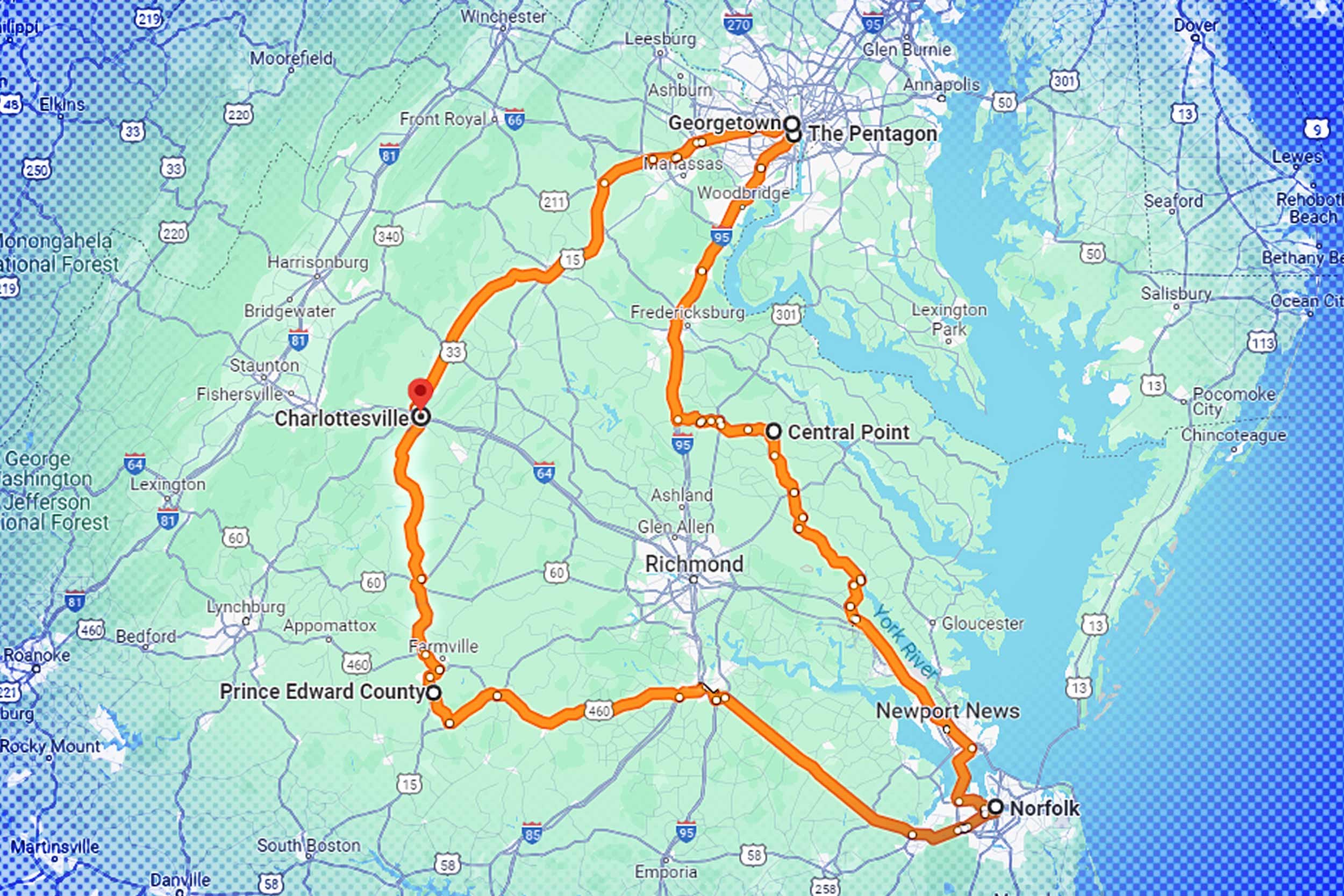

The seven destinations include stops in Charlottesville, Norfolk and Georgetown – see this Google Map for the route.

Stop 1: Gregory Hayes Swanson v. The Rector and the Visitors of the University of Virginia, Charlottesville

A portrait of Gregory Swanson, Class of 1951, was unveiled at the Law School in 2018. (Courtesy UVA Law)

A marker near the Jefferson-Madison Regional Library on East Market Street honors Gregory Swanson and his winning lawsuit. His portrait is located in the Law School’s Clay Hall.

When Gregory Swanson applied to the Law School’s Master of Law program in the fall of 1949, the law faculty voted to admit him. The University’s Board of Visitors, however, refused to admit him, citing state law mandating segregated education.

Swanson took his case to federal court in Charlottesville, represented by Oliver Hill, Martin A. Martin and Spottswood Robinson, in conjunction with the NAACP. On Sept. 5, 1950, the District Court ruled in Swanson’s favor. When Swanson registered as a law student 10 days later, he became the first Black student to attend on an integrated basis any formerly white institution of higher education in the states of the former Confederacy.

He paved the way for the trickle of Black students who immediately followed him to UVA, and to other Southern universities. And he paved the way for the University and the Law School to become the far more diverse, equitable and inclusive institutions we are today.

– Professor Risa Goluboff