Years before he would lead hundreds of Marines through a seven-month deployment in one of the most volatile and violent regions of Afghanistan, Seth Folsom was a third-year student at the University of Virginia, working on a paper.

The topic: the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan and how it compared to the American war in Vietnam.

“If somebody had told me when I wrote that paper that 20 years later I was going to be in Afghanistan fighting a counter-insurgency, I would have told them that they were on drugs,” Folsom said recently.

India Company’s Cpl Jacob Marler patrols through the Southern Green Zone alongside one of the many Afghan children caught in the struggle between the Marines and the Taliban. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by LCpl Armando Mendoza)

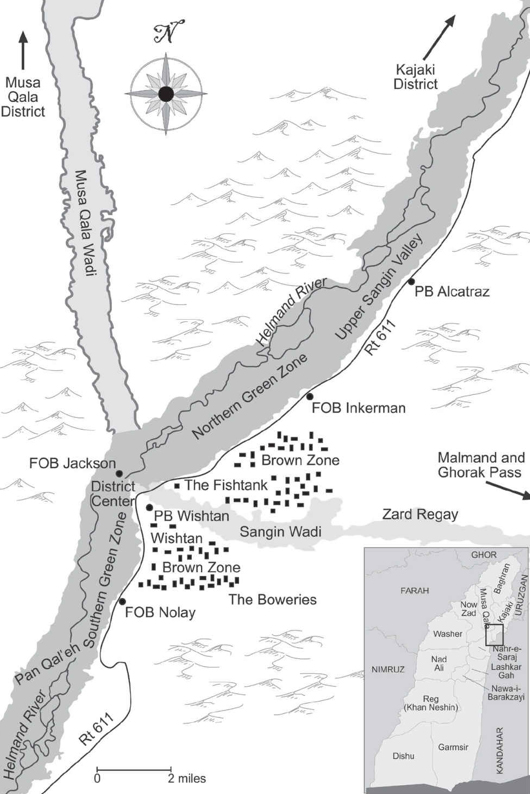

Since leaving Grounds as a newly minted international relations graduate in 1994, Folsom has been around the world as a career Marine officer, serving in Iraq, Afghanistan and elsewhere. He’s also written three books, the most recent chronicling his time as commander of the renowned 3rd Battalion, 7th Marines – known as the “Cutting Edge” – in Afghanistan’s dangerous Sangin Valley from fall 2011 to spring 2012.

“Where Youth and Laughter Go: With the ‘Cutting Edge’ in Afghanistan” may be the first nonfiction book written by an active duty Marine battalion commander. It chronicles the history of the Cutting Edge through its second deployment to Sangin, a region where the primary industry is agriculture, and the primary crop is the illegal poppy used in the heroin trade.

Folsom drew on his own daily journal entries to create the narrative, a harrowing account of day-to-day life in a war zone. The book documents Folsom’s careful balancing act between the battalion’s mission – stabilizing the region and preparing Afghan allies for eventual takeover – and his sense of responsibility to get as many of his Marines and sailors home safely as possible.

“At the age of 39, Mr. Folsom decided how to deploy 800 young men, knowing 80 of them would die, lose limbs or be ripped apart,” said Bing West, a Marine, former assistant secretary of defense and author of several best-selling books on Afghanistan and Iraq.

Now, as Folsom finds himself contemplating the eventual end of his military career, he’s also thinking about a new writing retreat for combat veterans to help them deal with acclimation to civilian life.

Time on Grounds

Folsom comes from a military family that moved to Virginia in 1985, around the time he began high school. Two years later, his older brother Ben came to Grounds as a first-year student.

“Watching his experiences here and getting an idea of the caliber of the education and the social experience he was having made the college decision very easy for me,” Folsom said.

In 1991, Seth Folsom, right, completed his first year and his brother Ben graduated. (Image courtesy Seth Folsom.)

Folsom’s wife, Ashley Christian, is a 1991 UVA graduate, though they didn’t know each other while in school. He initially participated in the Navy ROTC as a student before setting his sights on the Marine Corps, and was a member of the Chi Phi fraternity. Though different than a college such as West Point, UVA provided a well-rounded experience that helped prepare him for military leadership, he said.

“The writing and reading and analytical skills that I developed at UVA helped, but so did the social skills – and I’m not talking about parties at the fraternity,” Folsom said. “I’m talking about the ability to interact with people socially and not be a recluse, to not be so close-minded that I can’t accept another point of view.”

Seth Folsom in 1994, near his own graduation. (Image courtesy Seth Folsom)

“My father flew a patrol aircraft in the Navy, and he spent a lot of his time hunting Russian submarines,” Folsom said. “I became fascinated by that, by the Cold War itself, and by the role that Russia played in the world.”

Of all his undergraduate studies, two papers on the Soviet experience in Afghanistan would resonate years later for Folsom.

“Some of the questions that I asked myself at the time were about how the Russians had to have known what our country’s experience was in Vietnam. How could they get mired in South Asia? Then fast-forward and the same questions were being asked of us during our time over there.”

Military Service

Folsom was commissioned into the Marine Corps after graduation, and has served all over the world. In 2003, he was among the first wave of U.S. forces into Iraq as part of the invasion.

“What was more important to me was the story of the young Marines who were in my company.” - Seth Folsom

At the time, he was a company commander, leading about 130 Marines and sailors. As he’d done for most of his life, Folsom chronicled his experiences there through near-daily journal entries.

After returning from Iraq, he looked back over those journals and thought about the difference between the events and people he’d chronicled and the news coverage that saturated the airwaves, which often felt to Folsom like shallow military cheerleading.

“What was more important to me was the story of the young Marines who were in my company,” Folsom said. “What was missing in that coverage was the material about what was happening at the ground level: what we were facing in terms of weather and experiencing in our own actions and our own thoughts.”

Some of the Marines in his company had noticed Folsom writing in his journal each day and suggested he write a book about them. “It was maybe said in jest, but the more I thought about it, the more I thought that people needed to understand the stories of these guys and what they are doing,” he said.

The resulting book, “The Highway War: A Marine Company Commander in Iraq,” garnered positive reviews and set his methodology and purpose for future writing. He’s published two books since, “In the Gray Area: A Marine Advisor Team at War” in addition to “Where Youth and Laughter Go,” and he plans to donate his proceeds to the Bob Woodruff Foundation and other organizations that help military families.

Afghanistan

Folsom’s latest work, published in the fall, begins in 2011 as he assumes command of the Cutting Edge battalion – which, at its high point, included more than 1,200 Marines and sailors – and continues throughout its deployment to the Sangin Valley.

Afghanistan's Sangin Valley in Helmand Province. (Map from “Where Youth and Laughter Go: With the ‘Cutting Edge’ in Afghanistan”)

For the Marines, this meant few firefights with traditional opponents, but near-constant patrolling through pathways booby-trapped with improvised explosive devices, or IEDs.

For Folsom, the mission meant endless discussions with local leaders over chai tea, facilitating the flow of supplies to Afghan forces and working to prevent civilian causalities in the drone strikes he would green-light, often after aerial cameras spotted shadowy insurgents planting roadside bombs.

It’s clear in his writing that Folsom became frustrated with Afghan allies, who he felt were not taking full advantage of security paid for in Marine blood. Afghan soldiers were reluctant to go on dangerous patrols; there was systemic corruption in the local government. Afghan troops were often stoned, their leaders unhelpful. Tribal disputes transcended the conflict with the Taliban and made it difficult to tell who was fighting whom.

At night, insurgents planted homemade explosives in the areas around Marine bases and throughout the district. Every time the Marines would devise a new strategy to detect or destroy them, their makers would adapt.

Blast injuries became so commonplace that the Marines created a verbal code: “double-amp” meant double amputee, “triple amp” meant three limbs gone.

India Company’s LCpl Sean Holloway pauses with his metal detector and probes for an IED while on patrol in the Southern Green Zone. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by LCpl Armando Mendoza)

When a Marine was killed or injured, Folsom made a point of going out on patrol with the same unit the next day, a practice that kept him often in the field.

“Those patrols were through farmland and desert conditions, where really on any given day these guys could step on an IED and lose both their legs, if not their life,” he said. “By that point in the war, Afghanistan was kind of a blurb on the nightly news, even though there was a lot of fighting and dying going on in 2011 and 2012.”

The book’s title, “Where Youth and Laughter Go,” comes from World War I poet Siegfried Sassoon:

You smug-faced crowds with kindling eye

Who cheer when soldier lads march by,

Sneak home and pray you’ll never know

The hell where youth and laughter go.

West, himself a former combat Marine and decorated author, sees lessons in Folsom’s writing.

“He had the intelligence and perspective to know that the mission could not be accomplished,” West wrote in an email. “The American goal of sending our Marines to create a democracy in villages where the tribes had fought for centuries was insane. Yet we as a nation set that as our policy. And Folsom held the handle to one of the 10 most critical levers. He commanded one of the 10 pivotal battalions in the entire country. His book is riveting: How do you lead, knowing your men will die for a mission that will not be accomplished? Ask yourself as you read: What would I do?”

The safest, and least comfortable, route. Kilo Company's LCpl Casey Allison patrols with 1st Platoon through one of the Northern Green Zone’s ubiquitous canals - the only place sure to be free of IEDs. (Photo courtesy of Seth Folsom.)

But the book isn’t simply a litany of hopeless tasks; Folsom chronicles his battalion’s accomplishments and the Marines’ perseverance in the face of daunting conditions.

By the end of their deployment, the rate of IED injuries had decreased, and some of his command staff developed and codified an approach to anti-insurgent work that, Folsom wrote, changed the way the U.S. military operates in such areas. Successful regional elections gave him hope.

Beyond that, it was the way in which the Marines under his command performed under tremendous pressure that made Folsom grateful to be their commander, he said.

“To lead a battalion of Marines in combat is the privilege of a lifetime, but it is one that comes at a great cost,” he told a crowd assembled after the battalion’s return to the U.S.

Next steps

Returned from war and now a deputy division chief and operations officer for the Joint Chiefs of Staff in Washington, D.C., Folsom said he’s recently been thinking about what he’ll do when his military career is over. A father to two young daughters, he’s been in the Marine Corps his entire adult life.

Folsom’s own experience using daily journal entries – and eventually books – to process his war experiences has convinced him that writing is a viable tool for veterans as they readjust to society.

“I am a big fan of veterans using writing as a coping mechanism to work things out,” he said.

He and his family were in Montana over the summer, where a colleague of his wife’s owns a ranch. The idea of a writers’ retreat struck Folsom, who said he hopes to dedicate his post-military career to working with veterans, especially younger veterans.

“If I could get a small group of vets out to this place, where there are no distractions, there is barely even Internet, there’s nothing but the mountains and horses and peace and quiet, that would be the perfect venue to get these guys and gals in a circle and reiterate to them the importance of writing in the healing process of a combat veteran.”

Marines place dog tags on the upturned rifles symbolizing the seven men from the Cutting Edge who lost their lives in Sangin in 2011-12. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by LCpl D.J. Wu.)

Top photo: Marines from India Company’s 1st Platoon, resting in the courtyard of a wealthy Afghan’s compound, grieve after the death of LCpl Jordan Bastean during Operation Southern Strike. (Photo courtesy Seth Folsom.)

Media Contact

Article Information

April 18, 2016

/content/semper-fidelis-uva-alum-looks-back-war-writing-and-healing