John “Jack” Bertram, born in the waning days of the Woodrow Wilson administration, recently spent nearly two hours with a group of University of Virginia Air Force ROTC cadets. He discussed his experience as a B-17 bomber pilot over Europe during World War II.

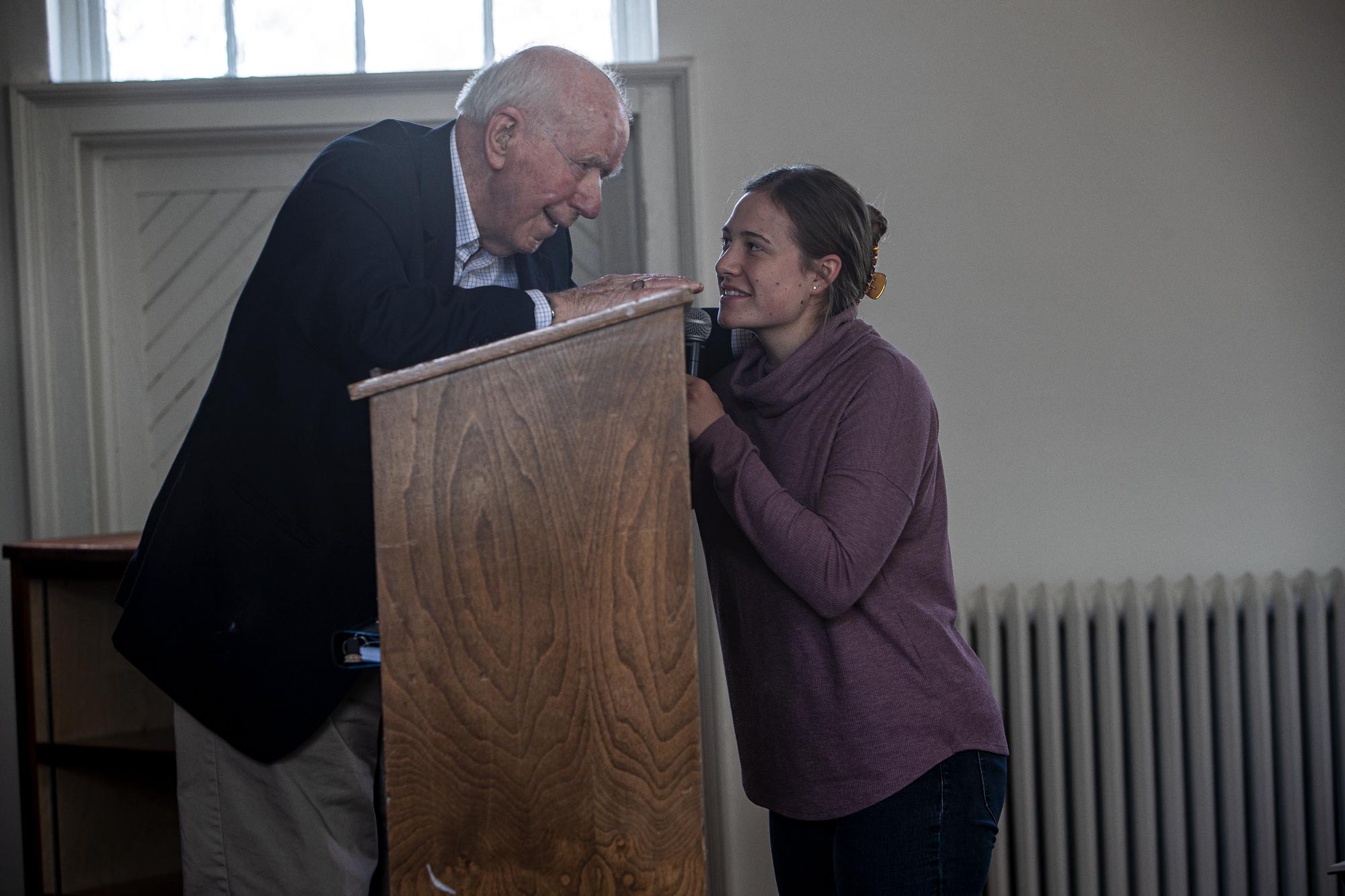

Bertram, who flew 36 missions over enemy territory, stood slightly stooped at the podium for his March 26 talk, held in the Colonnade Club on UVA’s Grounds. He surveyed the cadets. They were dressed in their civilian clothes, since it was not an official Air Force ROTC function.

The 101-year-old Bertram joked that the room, with its young, eager faces, hard wooden chairs and a black-out curtain across the south-facing windows, reminded him of the room where the B-17 pilots were briefed on their missions.

“A lot more effort went into creating this than went into those briefings,” he said.

Bertram was dapper in his blue blazer and khaki trousers, his white hair thinned on top. He spoke in a soft, but firm voice. His mind sailing back in time, Bertram recalled for the cadets some of what he experienced in a war that ended more than 50 years before they were born.

“The enormity of World War II was indescribable worldwide,” he said. “There were 16 million [American] men and women who served and there were 9 million overseas. And the training in this country was unbelievable. On the bad side, there were 12,000 deaths in training in the United States.”

He said the skies were full of airplanes around the training centers, and there was no air traffic control for them.

“When you were up there, you were on your own,” he said.

Bertram addresses Air Force ROTC cadets about his experiences flying in World War II.

Bertram, drafted in 1942, flew B-17 Flying Fortresses as a first lieutenant in the 95th Bomb Group, the only Bomb Group awarded three presidential citations. The group was stationed out of Horham, England, from June 1943 to May 1945. He flew two missions on D-Day, a moment in history about which the cadets were highly interested.

Bertram said the air crews, when they were brought in for their morning briefing, didn’t realize they were flying support for the land invasion of Europe – until the commander pulled back a curtain to reveal the maps.

“We were so excited, we were jumping up and down,” Bertram said. “We were thrilled to be part of D-Day. You can’t imagine how meaningful that was to us. That is what we were there for, and what we prayed for.”

While he flew two bombing missions on D-Day, Bertram gave credit to the troops on the ground.

When asked about his own perilous missions, Bertram described a bombing run to Munich. Anti-aircraft fire struck the plane after it had dropped its bombs, blowing a hole in the underside and disabling the crew’s oxygen. The damage forced them to a cruising altitude of 5,000 feet, down from their usual 17,000. He had to fly back to England, the crippled bomber unaccompanied by protective fighter planes.

His plane was also disabled in a mission to supply the French resistance. The crew were unable to close the bomb bay doors, and Bertram had to fly the plane back to England that way.

For his service, Bertram received the Europe Campaign Medal, the WWII Victory Medal, the Normandy Invasion Medal, an Air Medal with Five Oak Leaf Clusters, a Distinguished Flying Cross Medal and a French Legion of Honor Medal.