Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1852 anti-slavery novel “Uncle Tom’s Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly,” with its theme of the immorality of slavery, was the best-selling novel of the 19th century. The only book that sold more copies in the U.S. was the Bible.

In his new book, “Uncle Tom’s Cabin on the American Stage and Screen,” drama professor and theater historian John Frick of the University of Virginia’s College of Arts & Sciences chronicles how Stowe’s novel was adapted to theater and film – and details how, by the beginning of the 20th century, more than 400 separate companies traveled and performed some theatrical version of the story.

The “Tom Shows,” as they were known, were “ubiquitous and part of the common culture at the end of the 19th century and in the early 20th century,” Frick said – a theatrical phenomenon that bridged culture, commerce and ideology.

Frick said he wrote the book by chance. He was working on another book when Stephen Railton, a U.Va. English professor and specialist in American literature who created the website, Uncle Tom’s Cabin & American Culture, at U.Va.’s Institute for Advanced Technology in the Humanities, asked Frick if he would talk about performances of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” on stage at a conference at the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center in Hartford, Conn.

Frick really did not know much about Tom Shows before he began his research for the talk, but said he “found it absolutely fascinating.”

In the middle of his presentation, Frick realized that although he knew relatively little about the plays, at the time he was nevertheless the “only expert on ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin’ on the stage,” he said. He abandoned his other book to delve deeper in to its history and impact on American culture. “The novel had been widely studied, but the plays and films that followed had not,” Frick said.

“Tom Shows” were a small industry built on the genre known as moral reform dramas or melodramas, such as “The Drunkard” or “The Gambler,” which were widely received.

Theatrical entrepreneurs, people like P.T. Barnum and Boston showman Moses Kimball, “found there was money to be made in moral drama,” Frick said.

The first major theatrical production was by the George Howard Company, presenting a script developed by Howard’s cousin, George Aiken, that continued the abolitionist message of Stowe’s novel.

Frick said if he had to choose a favorite, the production by Howard and Aiken that traveled from Troy, N.Y., to New York City is his favorite because of its faithfulness to Stowe’s story.

This collaborative production also traveled to numerous towns, including Washington, D.C. When it played in Charlottesville, it was “blasted” by the Sons of the Confederate Veterans, Frick said. “In the South, it was dangerous to present a production that was anywhere near Harriet Beecher Stowe’s story.”

Later, productions “quickly went in the opposite direction and became racist,” Frick said. By the end of the 19th century, the “anti-Toms,” as they were known, “erased any abolitionist sentiment and were anti-black productions” that reflected the antebellum society in the South. Post-war legislation regulated where African-Americans could live and work and prohibited them from voting.

Early “Tom Shows” were performed in blackface, but after the Civil War, some African-American actors were included in productions. Ironically, the first instance where an African-American played the title role was in the South – in Kentucky, according to Frick.

The later, “patently racist” shows portrayed in a negative light the African-American stereotypes of the “pickaninny” black child, the dutiful, long-suffering servant and the dark-skinned mammy. At one point, three dramatic adaptations played simultaneously in New Orleans alone.

Across America, the traveling productions ranged from “ragged and amateurish” to more professional shows with good production values. Each year, “eight to 10 of these productions would come to town” and “people grew up hearing about ‘Uncle Tom,’” Frick said.

The productions launched the careers of a number of actors. The list includes luminaries in American theater – David Belasco, Lotta Crabtree, Otis Skinner and Joseph Jefferson, who was famous for his portrayal of Rip Van Winkle.

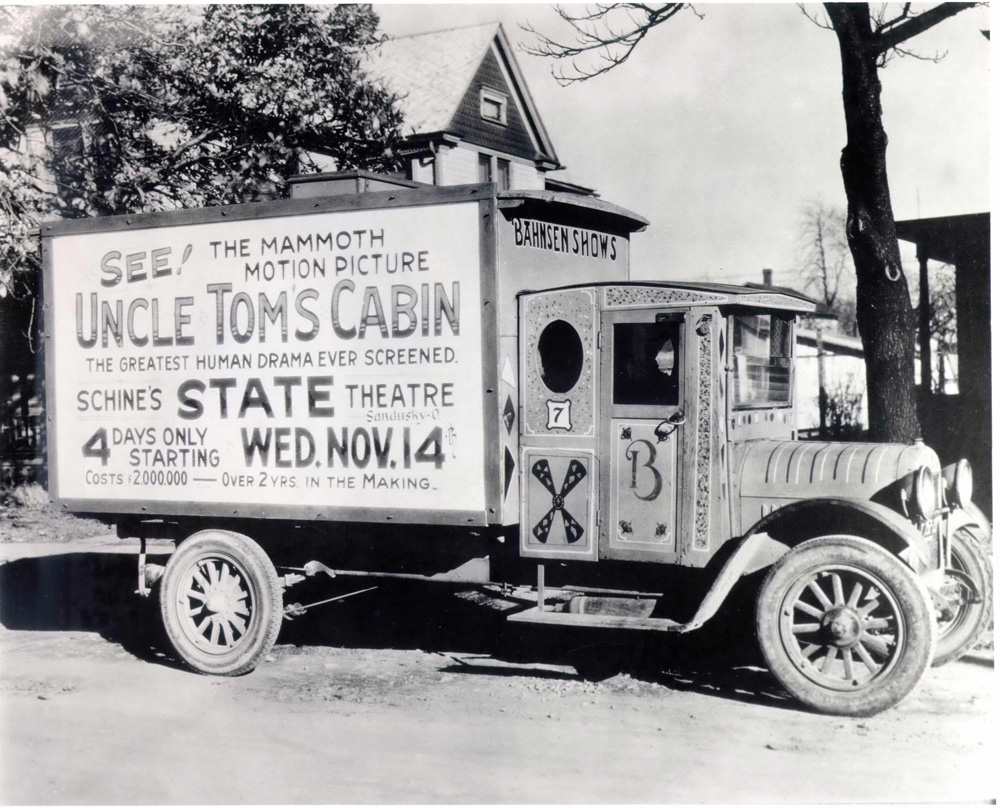

The first full-length movie of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” was a 1903 silent production by film pioneer Edwin S. Porter, a director with Thomas A. Edison’s film company. In 1927, Universal Studios released an epic version, shot on multiple locations at a cost of more than $2 million.

Plots, themes and characters endured well into the 1930s; even Judy Garland wore blackface in the 1938 movie, “Everybody Sing.” Character parallels can be found in the 1926 takeoff of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” by the comedic group Our Gang and the 1935 comedy drama, “The Little Colonel,” starring Shirley Temple.

In modern times, a 1987 television adaptation of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” starred Avery Brooks, Phylicia Rashad and Samuel L. Jackson.

Frick, who came to U.Va. in 1987 to teach theater history and American dramatic literature and history, will retire in December, but he’s still fascinated with how the story of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” evolved and spread. In January, he will go to England to research “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” on the British stage.

Media Contact

Article Information

November 12, 2012

/content/story-uncle-tom-s-cabin-spread-novel-theater-and-screen