What is your perception of a scientist? A woman? A man? What race is that person? Does the scientist work in a lab, a field site or an astronomical observatory? Perhaps all or any of these?

Educators have asked this question of elementary school students for decades – often by asking them to “draw a scientist” – and one response has persisted over the decades. Students tend to think of scientists as white men.

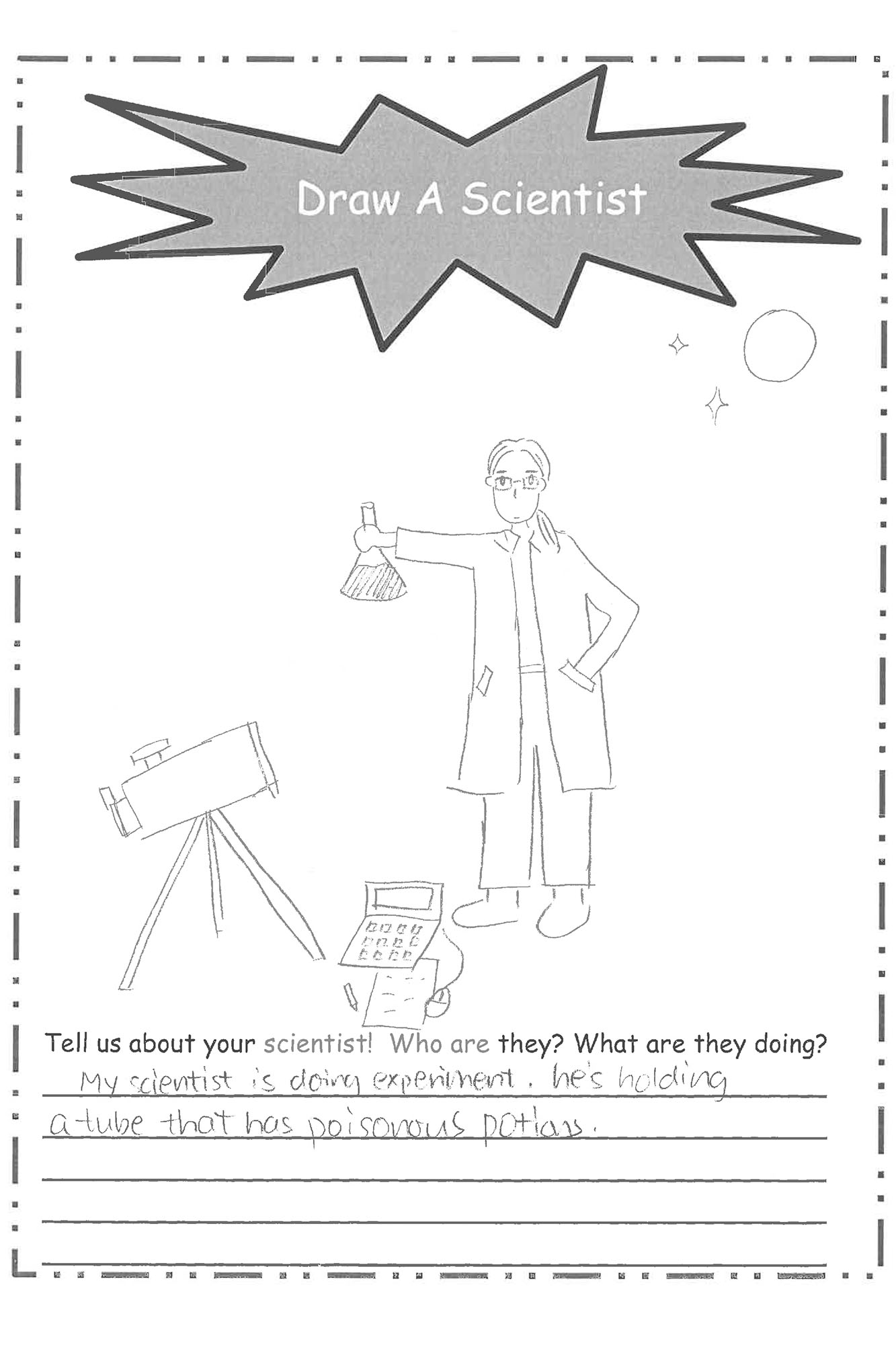

A newly published University of Virginia study has found that about two-thirds of students in a third- through fifth-grade extracurricular astronomy program perceive scientists as white men in labs, mixing chemicals – even as women and people of color increasingly work as scientists.

The study authors found that these perceptions persist even after elementary school students have been tutored under young female scientists in a program designed to increase understanding of and exposure to astronomy.

During the five-year period of the study, only 32% of elementary school students in the program drew female scientists at the beginning of study. After completing the program, only 35% drew women scientists. This was even as about half of the volunteer instructors in the program were female astronomy graduate students and role models who themselves intended careers in science.

The researchers also found that a third to a half of the elementary students drew scientists stereotypically, or while performing stereotypical activities, such as mixing chemicals, or building rockets or even bombs. After participating in the program, however, students did tend to depict scientists doing things other than working in laboratories.

The results were published recently in the journal Physical Review Physics Education Research.

“We are particularly concerned with the extent to which learned stereotypes are already affecting the way children think about science as a profession in elementary school – before they are making decisions in middle and high school about areas of concentration,” Kelsey Johnson, a UVA professor of astronomy, and study author, said.

Astronomer Kelsey Johnson founded the Dark Skies Bright Kids! educational outreach program in 2009 with some of her students. (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

The study was conducted to measure the effect on students’ conceptions of scientists at the beginning of and at the end of an 8- to 10-week astronomy club program held at Virginia elementary schools during the school year, and a related week-long summer camp.

“Obviously we were hoping to see some movement in childrens’ visualizations of scientists over the course of the 8-10 weeks the volunteers spend with them,” Johnson said. “Unfortunately, these results indicate that stereotypes that have been baked in before the ages of 10-12 are not so easy to undo.”

The program – called Dark Skies, Bright Kids! – was founded in 2009 by Johnson and her students as a way to bring extracurricular science to underserved students in Virginia. The program continues, with the goal to enhance upper-elementary student interest in science, encourage critical thinking and engagement, and to teach the concepts of astronomy with fun and exciting hands-on activities that encourage further exploration.

The program uses astronomy as a “gateway” science to introduce students to the night sky, to the practice of science broadly, and to help students understand that they can be scientists, and in fact are scientists whenever they investigate the world around them.

“A sense of belonging is a powerful force in determining the path people choose, and it matters whether children can visualize themselves in different professions,” Johnson said.

This is an example of the type of drawing that elementary school students produce when asked to draw a scientist. (Contributed image)

“By the time students are in the third to fifth grade, they may have already developed notions of what a scientist is, what scientists do, and how they look,” Christopher Haynes, the study leader and a graduate student in astronomy, said. “They may have ingrained ideas from sources such as TV shows and movies and history, that a scientist is a brainy white man in a lab coat and eyeglasses, mixing chemicals or making a rocket.

“This is especially likely to be true for girls or black students who come from lower income backgrounds. Because of these perceptual roadblocks, they often don’t imagine themselves as scientists, even after participating in a program that is designed to inspire an interest in science.”

To avoid potential bias in the elementary students’ perceptions, the “draw a scientist” test was administered, at the beginning of and after the program, by a school liaison or parent or guardian, rather than by a program volunteer.

“The impact of both stereotypes and role models should not be underestimated, and it is something we desperately need to improve in the sciences,” Johnson said. “Only 3.9% of physical and related scientists in the U.S. workforce are black, and 5.1% Hispanic, which tells us that diverse voices are being systematically excluded. Progress in science critically depends on being able to tap into diverse ideas. If everyone on a team approaches a problem in the same way, what’s the point of the team?”

Media Contact

Article Information

June 11, 2020

/content/study-elementary-school-students-tend-view-scientists-white-and-male