As swim team captain, Sean Conway spent much of his fall and winter in the clean, clear water of the University of Virginia’s Aquatic and Fitness Center. He spent most of his summer focused on a different kind of water, the kind coursing through Richmond’s storm and sewage system.

Minding the sewers is a dirty job, and more than one someone has to do it. Conway, a rising fourth-year engineering student, recently joined environmental consultants Brown and Caldwell as a summer associate to help solve some of the waterflow puzzles that underly Virginia’s capital city.

When Conway entered college, “Nobody told me I was going to be applying my knowledge to poop water,” he deadpanned.

Population growth and, yes, climate change are taxing Richmond’s aging system, a rare combined system where stormwater and municipal sewage flow through the same pipes. When water rises, so does the slurry, a portion of which oozes into the beloved James River.

Brown and Caldwell, a firm with broad geographic reach, is working to fix that. When Conway first researched the internship opportunity, the Leesburg native came across its water purification efforts out West. However, when the firm contacted him on the hiring app Handshake, the offer was closer to Grounds. The firm’s municipal branch has been addressing Richmond’s Environmental Protection Agency compliance headache for years.

Conway liked the idea of being able to perform data analysis and research presentations that will improve the environment. And the commuting distance meant that the standout collegiate swimmer could still train at the Aquatic and Fitness Center.

He signed on. In doing so, the clean-water swimmer became part of the ongoing solution to Richmond’s dirty-water dilemma.

Overflow, Backups and Bottlenecks

Richmond’s sewers are like ones you see in the movies. Twenty-three “combined sewer overflow” sites – the biggest pipes, with catwalks, spanning a distance so far you can’t see end to end – manage the deluge. They each can process hundreds of millions of gallons of discharge at a time.

“The scale of these things is absolutely insane,” Conway said.

The 150-year-old combined sewer system works well when the weather is dry. The wastewater travels without incident to the treatment plant, where the water is cleaned and returned to the James. But during high rainfall, stormwater enters the combined system and that can lead to raw sewage flowing into the James. Overflow sites are intentionally designed to spill over when they reach capacity. The goal for planners is to get them to the right size for modern conditions, so that overflow is a rare occurrence.

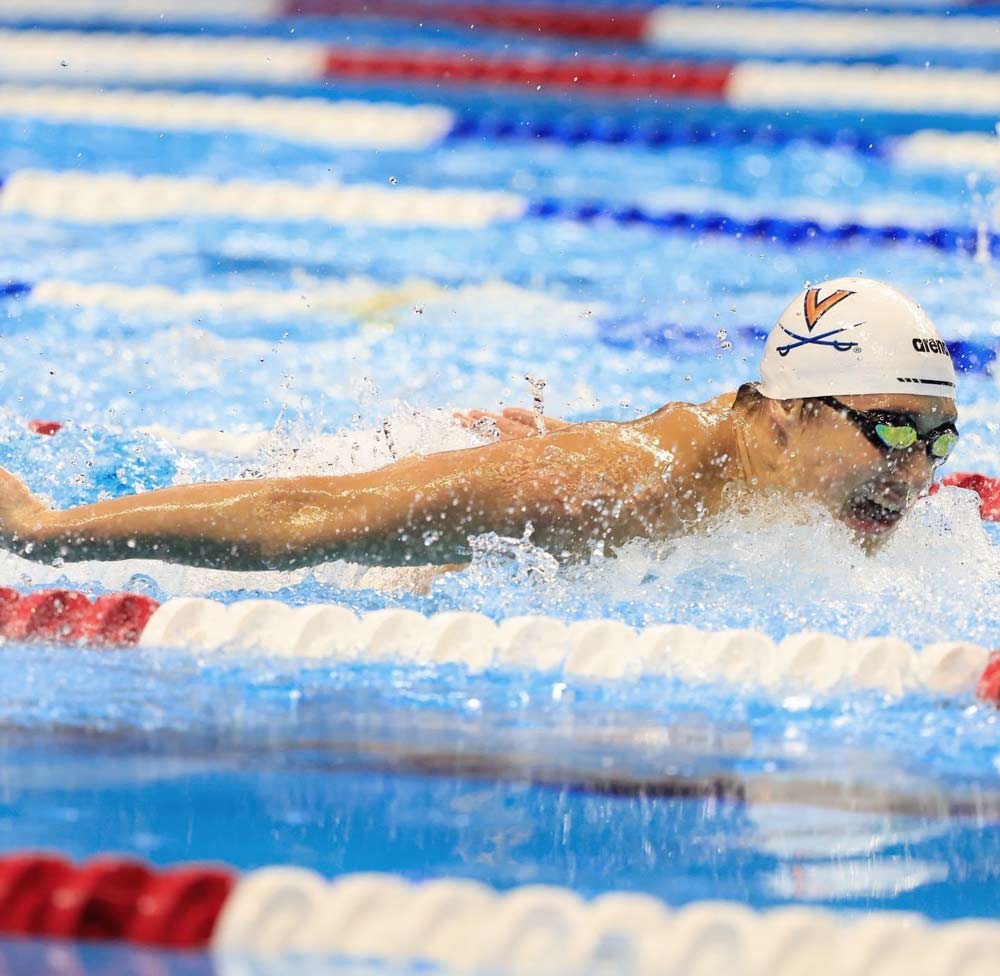

Conway spends the other half of his time in clean water. He’s team captain this year for the swim team. (Photo by Matt Riley, UVA Athletics)

Adding to the challenge, overall growth combined with redevelopment in areas not originally meant for high-density living – for example, converting old warehouse districts to apartments for young professionals – has resulted in increasing problems, including backups and bottlenecks.

The city last performed overall upgrades to its system in the 1970s. Since then, the city has invested in more individualized work, improving the combined sewer system by focusing on sewer separation projects, conveyance pipelines, tunnels, large storage facilities and the wastewater treatment plant.

The firm helps Richmond’s planners design selective improvements, because wholesale replacement of such a vast system wouldn’t feasible.

“The time frame it would take to rip the whole thing out and replace it would be impossible to keep up with,” Conway said.

Conway helps the team crunch water data. On his third day as an intern, in fact, he was asked to take a look at a complex set of rainfall statistics and make preliminary recommendations for a project. It was a sort of “litmus test,” he said.

Fortunately for the budding systems engineer, data analytics is kind of his thing.

“My project manager, Matt Pugh, sent the files over to me and said, ‘Go crazy.’ I’m very much someone who enjoys finding fun relationships and patterns in numbers.”

Interpreting a Steady Stream of Data

Like the waters being monitored, data is constantly streaming into Conway’s computer. The information comes from several hundred sensors placed under manhole covers around the city. The devices gauge the depths and how quickly the waters are rising or falling.

Conway inputs the data into the office’s primary information-sharing tool, a computer visualization dashboard. But he also produces alternate means to convey the information to clients, for whom the information needs to be more accessible. He even taught himself 3-D modeling.

He got a head start on how to prepare data for executives through a spring course, Systems Evaluation, taught by Reid Bailey.

“Immediately going from that course into an internship and doing the exact same thing was like, ‘Oh my gosh, I’m actually using something I learned in class,’” he said. “Seeing something that’s basically gibberish to a fresh set of eyes, that’s then turned into a useful report, is entertaining to me.”

Another course, Risk Analysis with James Lambert, more broadly prepared Conway to understand the ramifications of altering complex systems, he said.

But classroom projects are one thing. The internship has provided plenty of opportunities for consequential on-the-job training.

As part of a team, Conway is helping bridge the information gap as city planners make high-stakes decisions. How clearly he communicates may affect the future of parks and greenways currently being planned, he said.

Looking Toward the Future

With his summer position extended, Conway will continue to shoehorn big data for Brown and Caldwell until December.

He said he’s also looking forward to a near-future kayak trip on the James to check bacteria levels. Due to the city’s continued investment, the system currently keeps about 91% of the overflow in check. Ten new projects are planned to reduce the overflow volume by hundreds of millions of gallons more.

Meanwhile, Conway will wait to hear if he has been accepted into the School of Data Science’s graduate program.

The student has an extra year of collegiate athletic eligibility due to the 2020 COVID-19 year, so he would be in a position to continue to compete for the swim team while pursuing his graduate studies. He has routinely placed highly in swim competitions, including scoring a second-place finish last year at the University of California, Berkeley in the 200-meter individual medley, for which he also holds a UVA pool record. The medley is for well-rounded swimmers and combines butterfly, backstroke, breaststroke and freestyle. If he gets the extra year, he hopes to convert it into a berth at an international meet that will be held in China.

Regardless, he’s preparing for the day when he’ll have to hang up his goggles. The duality of his recent focus – clean water and dirty water – hasn’t been lost on him.

“It’s ironic,” he said. “I do hope that water will continue be a part of my life, whether or not I decide to stay in the stormwater-wastewater industry.”

Although on-site sewer work isn’t an everyday part of his job, Conway sometimes goes out on assignments with his boss for manhole and repair inspections, or to review “isolated incidents” – when something goes wrong. He said those moments have helped him appreciate what he, and most of us, take for granted, which is the miracle that happens every time we press a commode handle.

“We were working on one case where somebody’s third-floor toilet literally shot out as a geyser,” Conway said. “I definitely know that man was taking it for granted just until that point.”

Media Contact

Communications Manager School of Engineering and Applied Science

williamson@virginia.edu (434) 924-1321

Article Information

October 10, 2025