A new study from the lab of an adolescent psychologist at the University of Virginia has found more evidence that teens who are not adept at managing relationships will show physical signs of premature aging as adults.

“Teenagers who don’t learn to manage the give and take of relationships with their peers, who can’t handle disagreements in a way that also preserves relationships, and also don’t stick up for themselves, their bodies have aged more by age 30,” said Joseph Allen, the Hugh Kelly Professor of Psychology.

Allen said some young people immediately get angry and hostile when struggling with their peers during a disagreement, while others back down repeatedly, unwilling to express their own preferences or point of view. Both approaches, he said, are unhealthy.

“The kids who do well, in contrast, are kids who are able to disagree without being disagreeable and to look for common interests and to sort of manage the fact that people have different interests,” he said.

Joseph Allen, the Hugh Kelly Professor of Psychology, head’s UVA’s Adolescence Research Group. (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

He added that the ability to cope starts at home, based on how parents manage disagreements with their children, cueing the child’s behavior.

These dynamics create a snowball effect. Allen said the teen years are ground zero for learning to practice with adult-like relationships, and teens who figure it out do well later in life. Those who do not are setting themselves up for a life of chronic stress that leads to a slew of health problems.

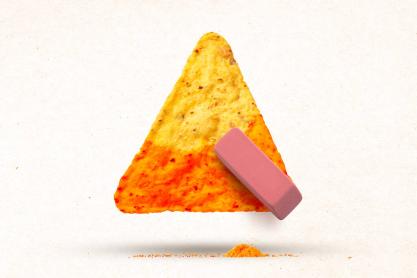

That evidence was found studying the individual’s epigenomes – those biological marks found on DNA and histone proteins (the spools around which DNA wind) that determine how well (or poorly) a cell will function.

“The epigenome is what tells genes when to turn on and when to turn off,” Allen said. Over time, a well-functioning epigenome in childhood can get “rusty” for those with a history of poor relationship management.

“The best analogy is that it’s like a CD or a DVD that gets scratched. The information might still be there, but it doesn’t get conveyed as well, and the result is our body doesn’t function as well,” he said.

Because of this damage, scientists are capable of scanning people’s blood and seeing into the future.