__________________________

Notes

1. “Make Them Wear Badges,” College Topics, April 30, 1890. “It is possible that injustice may be done to the aforesaid visitants in putting all the thieving upon them – as it is not likely they would care for law books or boxing gloves – but it is probable that most of it is done by them, and at all events it can do no harm to make the experiment and it will have the salutary effect of relieving the landscape of a very disagreeable feature.”

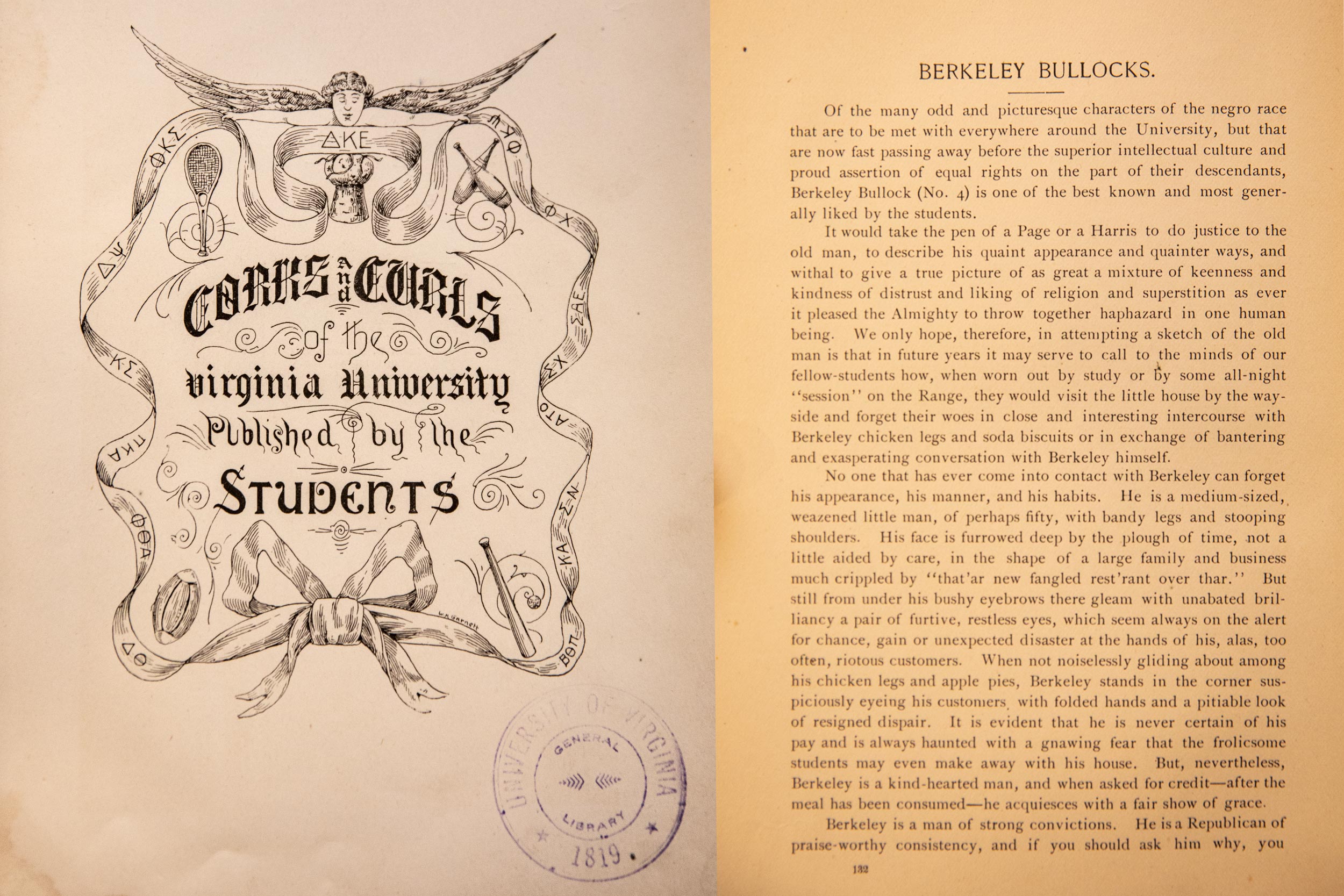

2. “Berkeley Bullocks,” Corks and Curls of the Virginia University, Published by the Students, No. 4, 1889-90, pp. 132-133. Bullock’s name is misspelled “Bullocks” in the heading but spelled correctly on first reference immediately below. http://search.lib.virginia.edu/catalog/uva-lib:2251087/view#openLayer/u…

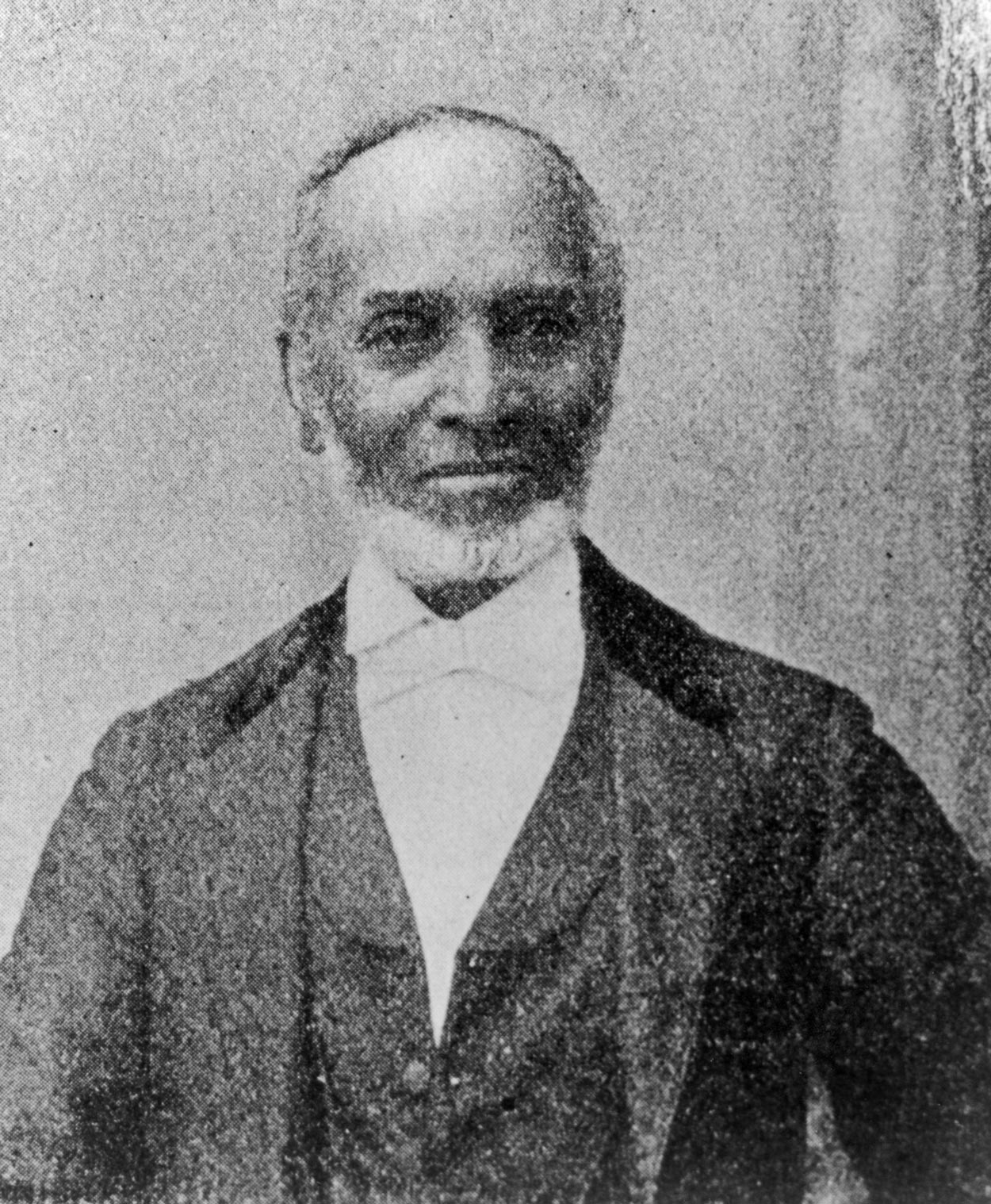

3. The author is grateful to Bullock family descendants, particularly the late Jean Henderson, for contributing their research and family memoirs to this revised portrait. Local researchers Edwina St. Rose, Sam Towler, Ann Carter, Bob Vernon, and others provided helpful leads on sources and context. The Carter G. Woodson Institute for African-American and African Studies, under the leadership of then-director Reginald D. Butler (1996-2005), provided intellectual and institutional support through its Ford Foundation-funded Center for the Study of Local Knowledge.

4. Bullock’s headstone lists his birth date as 1830. His obituary, dated Jan. 27, 1908, gives his age as 77, which would put his birth date in 1831 or 1832. See “Funeral for Burkley Bullock,” The Daily Progress (Charlottesville, Va.), Jan. 27, 1908, p. 3.

5. Fanny Lee Nolian Bowles Leach, “Family History,” undated, p. 5. Photocopy courtesy of Brenda Calloway.

6. Early Charlottesville: Recollections of James Alexander, 1828-1874, ed. Mary Rawlings (Albemarle County Historical Society, 1942): 20. The house, known as “Social Hall,” is still standing.

7. See sketch of Berkley B. Bullock, Sr., prepared by his great-granddaughter, Jean L. Henderson, in “Linking the Branches of the Bullock Family Tree to Our Charlottesville Roots, 2000.” Used by permission.

8. “Charlottesville, Va. Letter. The Only Surviving Ex-Slave of the Renowned Thomas Jefferson Visiting Once More the Place of His Nativity,” The Colored American, June 23, 1900, p. 9: “While with the family of Col. John R. Jones he taught all of the slaves to read and write, among whom was Mr. Burkley Bullock, who for several years was the proprietor of the only restaurant at Union station in this city.” Born at Monticello in 1815, Fossett would have been 15 years older than Bullock. See entry for “Peter Fossett” in the Thomas Jefferson Encyclopedia, https://www.monticello.org/site/research-and-collections/peter-fossett

9. Charles W. Bullock Sr., undated; Pearl M. Graham papers, Howard University. The text of a subsequent letter from Charles Bullock to Pearl M. Graham, dated Oct. 10, 1949, suggests that Graham solicited his recollections of Peter Fossett earlier that same year.

10. “Once the Slave of Thomas Jefferson: The Rev. Mr. Fossett, of Cincinnati, Recalls the Days When Men Came from the Ends of the Earth to Consult ‘the Sage of Monticello’ -- Reminiscences of Jefferson, Lafayette, Madison and Monroe,” The New York World, Jan. 30, 1898, p. 33.

11. Interview with Horace Tonsler, Charlottesville, Va., date unknown, reprinted in Weevils in the Wheat: Interviews with Virginia Ex-Slaves, eds. Charles L. Perdue, Jr., Thomas E. Barden, and Robert K. Phillips (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1976): 286-287. Original Source: Negro in Virginia, MS version, draft no. 1, chap. 13, p. 14.

12. On Jones’s “financial troubles,” see the Rev. Edgar Woods, Albemarle County, Virginia (Harrisonburg, Va.: C.J. Carrier Company, 1978; first published in 1901): 239.

13. For bankruptcy sale advertisement, see “Thirty Six Valuable Slaves for Sale,” Richmond Enquirer, Oct. 30, 1855.

14. For names of those sold at auction and their buyers, see deed of sale dated Nov. 16, 1855, Albemarle County Deed Book 54, pp. 387-388. Thanks to Sam Towler for locating this deed and Edwina St. Rose for sharing her scanned copy. For Towler’s speculation on the sale/dispersal of Bullock family members, see his comments on “Still More on Peter Briggs,” Encyclopedia Virginia, The Blog, Nov. 5, 2013. https://www.evblog.virginiahumanities.org/2013/04/still-more-on-peter-biggs/.

15. Fanny Bowles Leach, “Family History,” undated, p. 5. Photocopy courtesy of Brenda Calloway.

16. See deed “made this 1st day of September, in the year One Thousand Eight Hundred and Sixty Eight -- between Eugene O. Michie of the first part and William Brown & Berkeley Bullock of the 2nd part,” Albemarle County Deed Book No. 63, p. 525-526.

17. Albemarle County Chancery Cause, William Brown &c. vs. R.R. Prentiss, Trustee, Index No. 1872-018, Case No. 561 16. Library of Virginia.

18. The Browns moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts; see 1880 U.S. Census, Middlesex County, City of Cambridge, Mass., Ward 1, P. 66.

19. The sale was not recorded until 13 years later, after Shackleford’s death. Bullock requested that legal title to the tract be conveyed to him since the money he owed on the property had “long since been paid in full.” See deed “dated May 12th 1884, between said Rebecca Shackleford , Richard Shackleford, & Louisa Shackleford, his wife, of the fist part, and said Berkeley Bullock of the second part . . .” Albemarle County Deed Book 83, p. 383.

20. U.S. Census, 1880, Agricultural Supplement. Schedule 2, Productions of Agriculture in Charlottesville District in the County of Albemarle, State of Virginia, P. 5, Supervisor’s District 3, Enumeration District 11.

21. U.S. Census, 1880, Agricultural Supplement.

22. See entries for “Wright's Railroad Dining Room” and “Bullock Berkeley col” under “Restaurants” in Turner's Charlottesville City Directory, 1888-89, Commercial Directory, p. 120. Both restaurants were located at the “VM junction” (Virginia Midland junction).

23. Corks and Curls of the Virginia University, Published by the Students, No. 4, 1889-90, pp. 132-133.

24. Charter of the Piedmont Industrial and Land Improvement Co., April 9, 1889; Charter Book 1, Charlottesville City Clerk’s Office.

25. The (Richmond, Va.) Planet, May 17, 1890, p. 4. Report from Charlottesville.

26. The (Richmond, Va.) Planet, Nov. 7, 1891, p. 4. Report from Charlottesville.

27. “Worthy Colored Man Dead,” The (Charlottesville, Va.) Daily Progress, Jan. 25, 1908, p. 1.

28. “Funeral for Burkley Bullock,” The (Charlottesville, Va.) Daily Progress, Jan. 27, 1908, p. 3.

29. “Grave Concern: Local Group Preserves Black Cemetery,” Cville Magazine, June 8, 2017. https://www.c-ville.com/grave-concern-local-group-preserves-historic-bl…