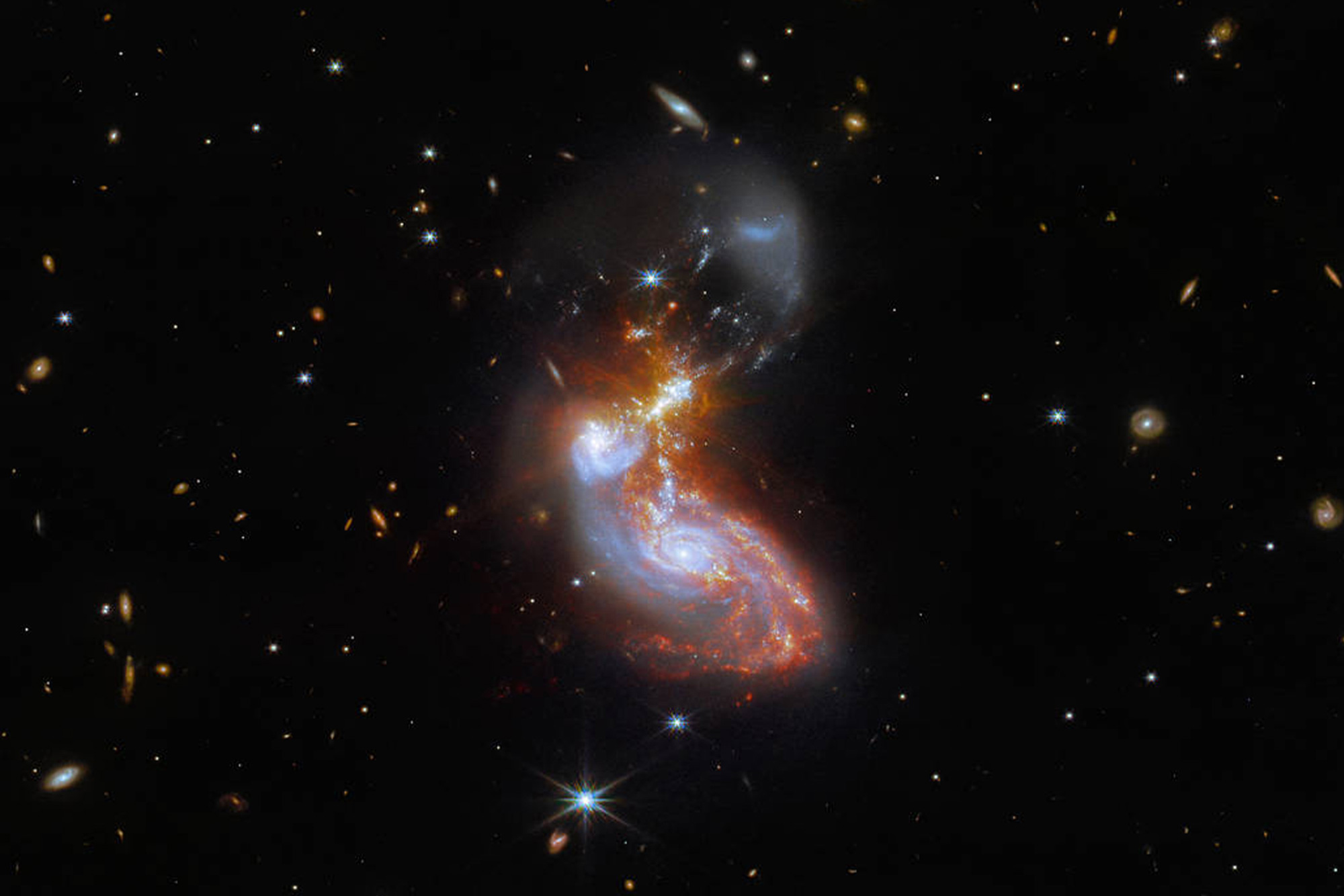

The James Webb Space Telescope has provided scientists with previously unimaginable details of galaxies millions of light years away. Now astronomers including the University of Virginia’s Aaron Evans are using the stunning images and data to study what’s happening at the cores of other galaxies.

Evans is among the astronomers leading the first round of 13 Early Release Science projects selected by NASA and its partners, the European Space Agency and the Canadian Space Agency, to test the Webb Telescope’s capabilities.

Wednesday night, Evans will appear on the PBS science series “NOVA” to discuss what he and others have learned already from the Webb Telescope and its images of faraway galaxies, stars and exoplanets.

“It’s taken 300 million years for the light from these galaxies to reach us,” Evans said, “so we’re basically seeing these galaxies as they appeared 300 million years ago.”