Peyton Skipwith stood out as both an accomplished stonemason and a pious man at the Bremo plantation of John Hartwell Cocke, one of the first members of the University of Virginia’s governing Board of Visitors.

Skipwith, an enslaved laborer freed in 1833, quarried stone for buildings at UVA, including the Anatomical Theater, the only building that Thomas Jefferson designed for the University outside of the original Academical Village.

On Thursday, a new building likely sitting on the quarry’s location was dedicated as Skipwith Hall in his honor, one of several events celebrating Founder’s Day. Located in the Facilities Management complex along McCormick Road, the building was completed in January 2016 and houses administrative offices.

Along with President Teresa A. Sullivan giving remarks at the naming ceremony, Dr. Marcus L. Martin, UVA’s vice president and chief officer for diversity and equity and co-chair of the President’s Commission on Slavery and the University, and fellow co-chair, historian Kirt von Daacke, updated the audience on the commission’s work and efforts to find opportunities to recognize enslaved laborers who helped build the early University and keep it running.

About 25 descendants of Skipwith’s relatives joined members of the UVA community, including three descendants, Carol Malone, Bill York and Joe Creasy, who spoke about the significance of having their family member honored.

Like his close friend Thomas Jefferson, Cocke owned slaves, even though he thought slavery a curse upon the South. He selected slaves to educate, Skipwith among them. Cocke believed the best solution was freeing black people – as long as they moved to a new, experimental American colony for ex-slaves, Liberia in Africa. Hence, he emancipated Skipwith; his wife, Lydia; and their six children, and funded their trip. But they had to leave.

Facilities Management historian Garth Anderson researched the stone quarry site and soon found the connection between Cocke and Skipwith.

“Skipwith did more than cut stone,” Anderson said. “He was a historic figure. You see it through [Skipwith’s] letters – 15 years of struggles and successes. The distance allowed for stories to be told.”

Although his wife and one of his daughters died within the first year after journeying across the Atlantic, Skipwith and the rest of his family persevered in Liberia and helped create a new nation.

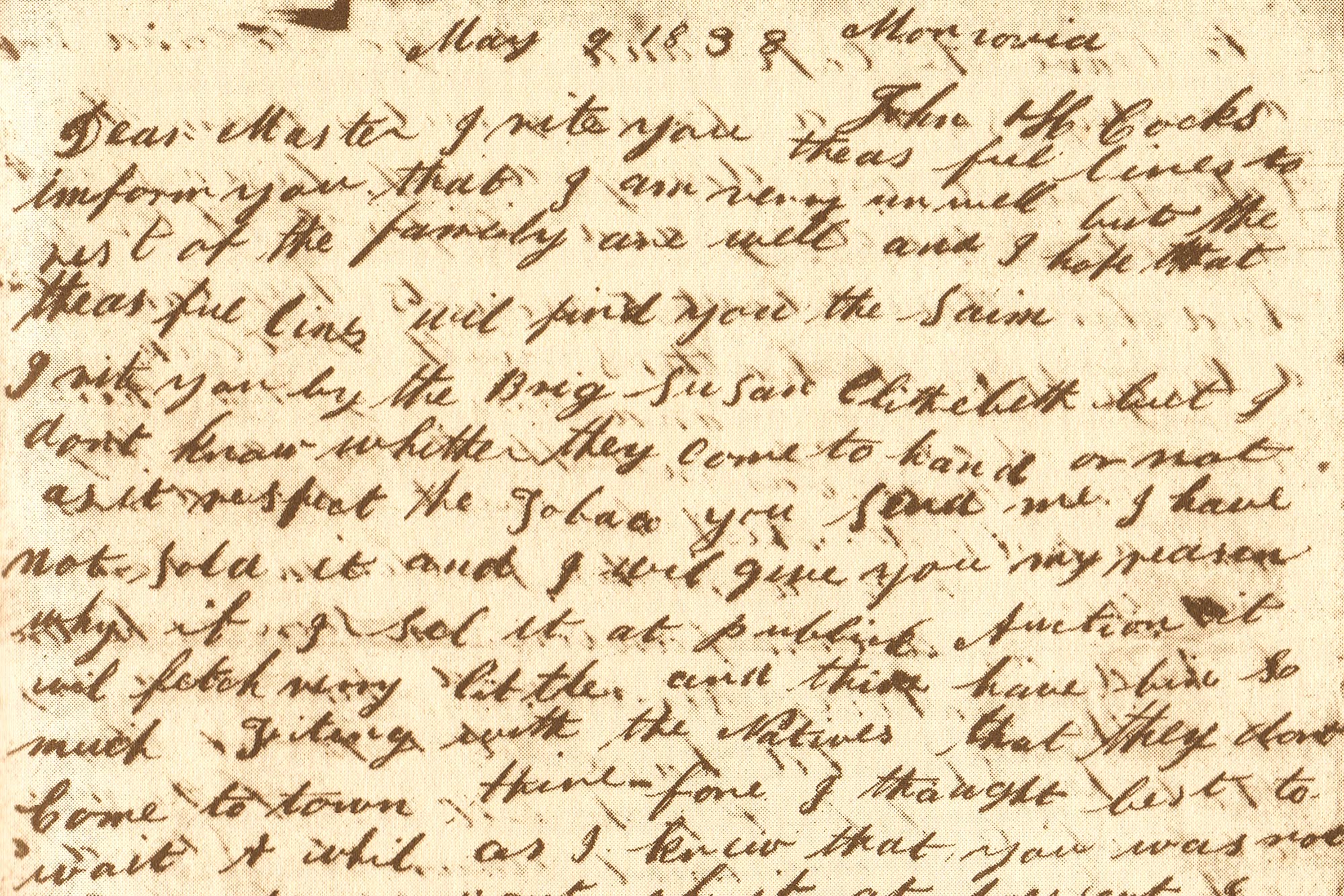

Anderson said one resource was especially helpful: the extraordinary 1978 book, “Dear Master: Letters of a Slave Family,” edited by historian Randall M. Miller, who was the keynote speaker at Thursday’s Skipwith Hall ceremony. The book – the largest historical record of any U.S. slave family – contains letters Peyton and his family wrote to Cocke and his other family members after the Skipwiths settled in Monrovia (named for James Monroe), Liberia’s capital.

After Peyton Skipwith and his family moved to Liberia in 1835, they wrote more than 50 letters to their former owner, John Hartwell Cocke, discussing the family’s health and the difficulties of creating a new life in Africa. (Image: Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library)

At the ceremony, Anderson said the letters sat silently in UVA’s Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, which holds the Cocke family papers, until Miller’s edition awakened their voices.

None of Cocke’s letters to the Skipwith family survive, according to Miller. Also unknown is whether any of Peyton’s direct descendants returned to America.

Along with the letters from Liberia, Miller’s book includes letters from Peyton’s brother George and daughter Lucy, who were sent to live in Alabama. Cocke moved them and other slaves to his experimental cotton plantation there, where the enslaved laborers conducted their work and lives with little white supervision.

Miller spoke emotionally of how his work on the Skipwith book not only enabled him to better get to know these people of the past, but also – unusual for a historian – led him to know the living descendants, who “have taken him in.”

He praised UVA and other universities for confronting their painful entanglements with the history of slavery, “searching their records and their souls.” Students, staff and faculty members have demanded the truth about the past, he said, and UVA has not shirked from telling the true stories that can be recovered and considering what meanings such a past has for today.

“You’re not just rewriting history, you’re making it right,” he said. This new narrative reveals the work of the enslaved laborers and presents them as “real people.”

The descendants thanked UVA for recognizing their ancestor. “It’s not only personally significant, but it also helps us realize the impact of the University’s push for diversity,” Creasy said. He credited another person in the audience, Andi Cumbo-Floyd, with first contacting him about his relationship to the Skipwith family.

Cumbo-Floyd, who is white, grew up at the Bremo estate, where her father was the caretaker of the still-private residence. A historian and writer, she consulted Miller’s book and wrote about the Skipwith descendants in her 2013 book, “The Slaves Have Names.”

Creasy also pointed to the first Skipwith descendant who is now a UVA student. Dwayne Creasy Jr., a resident of Powhatan, transferred to UVA, and after taking this year off, will return in the fall as a chemical engineering major.

Dwayne said he and his relatives felt the occasion’s impact as they read aloud some of the letters earlier in the day at the Special Collections Library. “It’s profound,” he said. “It shows the progress that has been made.”

York, a descendant of Peyton’s niece, Lucy, said his mother gave Miller’s book to her family in 1990. “It brought a family together,” he said. York said the family names were recycled down through the generations as a way of continuing the family history.

The ceremony concluded with Sullivan, Martin and von Daacke unveiling the plaque that summarizes Skipwith’s life. It will be installed in the entrance to Skipwith Hall.

Though its name is rooted in history, the two-story, 14,353-square-foot building is firmly modern. It was designed to provide maximum use of natural light with highly efficient, sustainable features, including green roofs, photovoltaic panels, LED lighting and highly efficient mechanical systems.

Media Contact

Article Information

April 13, 2017

/content/uva-building-named-former-slave-and-stonemason-peyton-skipwith