Bringing together people from all walks of life, the first-ever “Liberation and Freedom Day,” held Friday at the University of Virginia and Jefferson School African-American Heritage Center, celebrated the end of slavery in Charlottesville 152 years ago.

More than 150 people — black and white, of various ethnic backgrounds and religious faiths, young and old, students, professors and workers, community and political leaders — participated in the celebration that began at the UVA Chapel and included a march down Main Street to the Jefferson School.

The Charlottesville City Council proclaimed March 3 to be “Liberation and Freedom Day,” commemorating the date when enslaved individuals were able to follow the path to freedom after Union troops met with UVA and city officials on the spot where the chapel was later built.

At the time of the Civil War, 14,000 out of 26,000 Charlottesville and Albemarle County residents were enslaved.

After the carillon bells rang at 4 p.m., Dr. Marcus Martin, UVA’s vice president for diversity and equity, and the Rev. Tracy Howe Wispelwey, associate pastor of Westminster Presbyterian Church and a member of United Ministries of UVA, led a service at the chapel that included religious leaders from several faiths offering their songs and prayers.

Scroll through the slideshow below for images from the service.

“As co-chair of the President’s Commission on Slavery and the University, I am thrilled to see Liberation and Freedom Day established and become an annual event,” Martin said. “I can only imagine the bells of jubilation and joy in the hearts of so many enslaved who were finally free at last.”

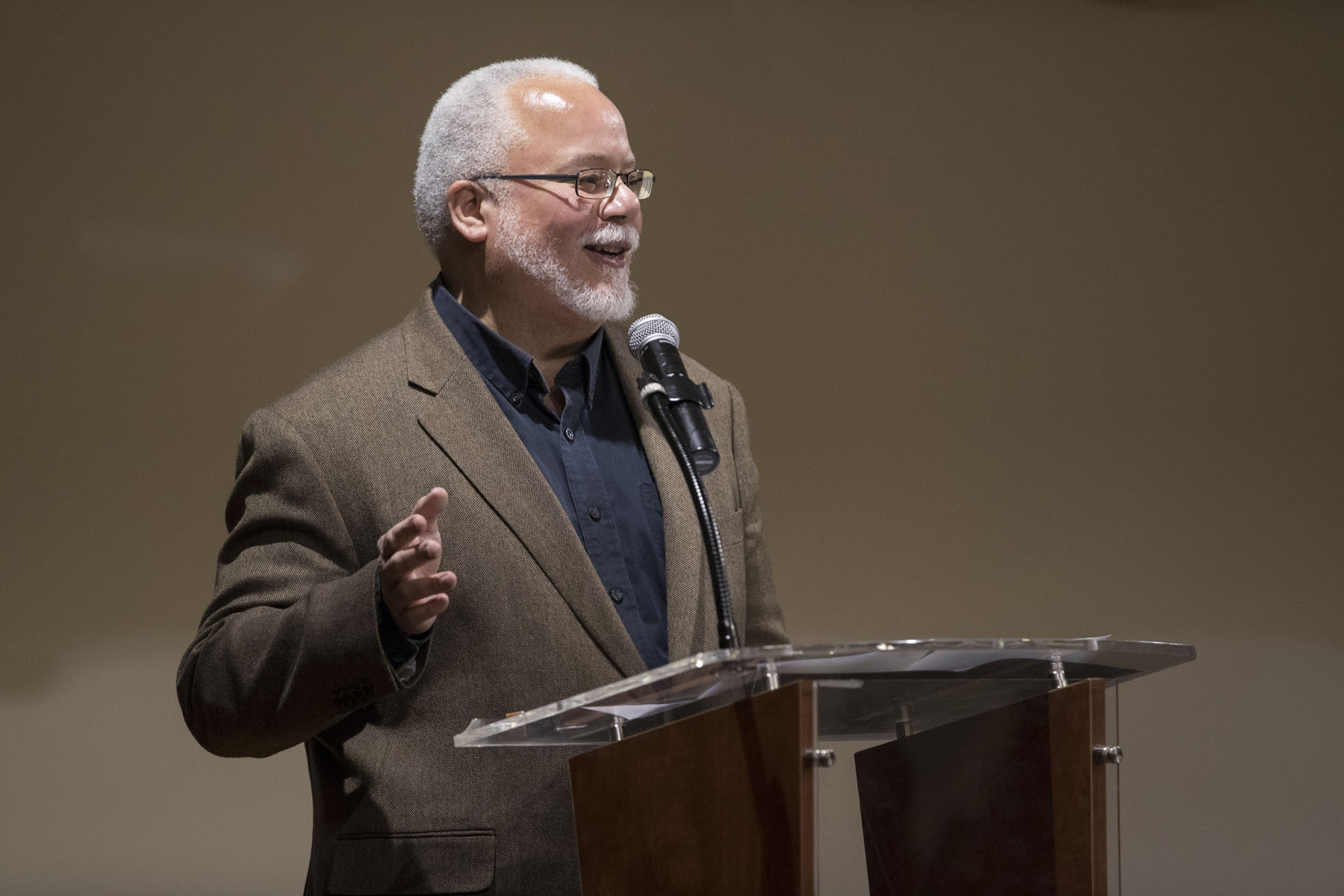

At the Jefferson School African-American Heritage Center, the slate of speakers included John Edwin Mason, UVA associate professor of history; professor Gary Gallagher, director of UVA’s John L. Nau III Center for Civil War History; and UVA President Teresa A. Sullivan.

Mason served as vice chair of Charlottesville’s Blue Ribbon Commission on Race, Monuments and Public Spaces, which recently shared its recommendations on how the city might publicly express its history more accurately and inclusively. One recommendation was establishing “Liberation and Freedom Day.” Mason thanked the city and credited two women for doing much of the research: commission member Jane Smith and UVA assistant professor Jalane Schmidt, who helped organize the day’s events.

“March 3 previously was seen as a day of defeat,” Mason said, but records of Union troops described witnessing joy and blessings from liberated African-Americans.

Not everyone leapt into freedom that day, although hundreds reportedly followed the troops. “But it was the moment freedom was on the horizon.” Mason mentioned that his enslaved great-grandfather from Clifton Forge somehow escaped and served with a Union cavalry from Massachusetts.

According to research at UVA’s Nau Center for Civil War History, he was not alone.

Gallagher, an expert on Civil War history, said the center’s scholars have recovered the names of 240 black men born in Albemarle County who fought for the United States during the war.

Even though the legacy of the Civil War is still raw, “the Lost Cause” of the Confederacy is only one story, he said. The history of the black men who put on blue uniforms and joined 70 different regiments has not been similarly commemorated. They demonstrate the diaspora of enslaved African-Americans who found their way to freedom, Gallagher said.

“There’s an idea – build a monument with their names on it,” he said, to applause.

Of the liberation from slavery, Sullivan said, “It’s a story that needs to be told, in our time and for all time … a story of our shared history in this community, and our common humanity.”

The commemoration should not be “a day of somber reflection,” but “a day of victorious reflection,” Sullivan said, “because we’re celebrating a moment in the history of our community and our nation when freedom won the battle over bondage.”

Among other examples of “victorious reflection” at the event, the first “Freedom Fighter” awards were given, recognizing three local residents: community activist Deirdre Gilmore; Eddie Harris, who started a prison program on fatherhood; and Zyahna Bryant, a Charlottesville High School sophomore who endured threats after speaking out for moving the Robert E. Lee statue.

Vice Mayor Wes Bellamy read aloud a letter from Gov. Terry McAuliffe, commending the city and all those involved for their efforts to further equity, inclusion and dignity for all.

As with other institutions and locales across the nation in recent years, the City of Charlottesville and the University each have striven to recognize the role of slavery in their histories.

Last year, UVA’s Board of Visitors selected a design team to plan a memorial to UVA’s enslaved laborers, scheduled to be installed by 2019, when the University celebrates its bicentennial.

Media Contact

Article Information

March 5, 2017

/content/uva-city-celebrate-local-history-liberation-slavery