One of the most beloved stories in the world about the girl who fell down a rabbit hole and into another world, “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” turns 150 this year. Several people at the University of Virginia have joined the “Mad Tea-Party,” so to speak, to celebrate this incredible novel’s “very merry unbirthday.” (That’s from a song in the Disney film version.)

There’s an exhibit showing illustrations of “Alice” in the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, curated by fifth-year student Susan Swicegood, on display through Sept. 18.

University Professor Michael Suarez, director of the Rare Book School, wrote an essay about the history and worldwide phenomenon of the “Alice” books and will speak at an October conference in New York City devoted to translations of Lewis Carroll’s work.

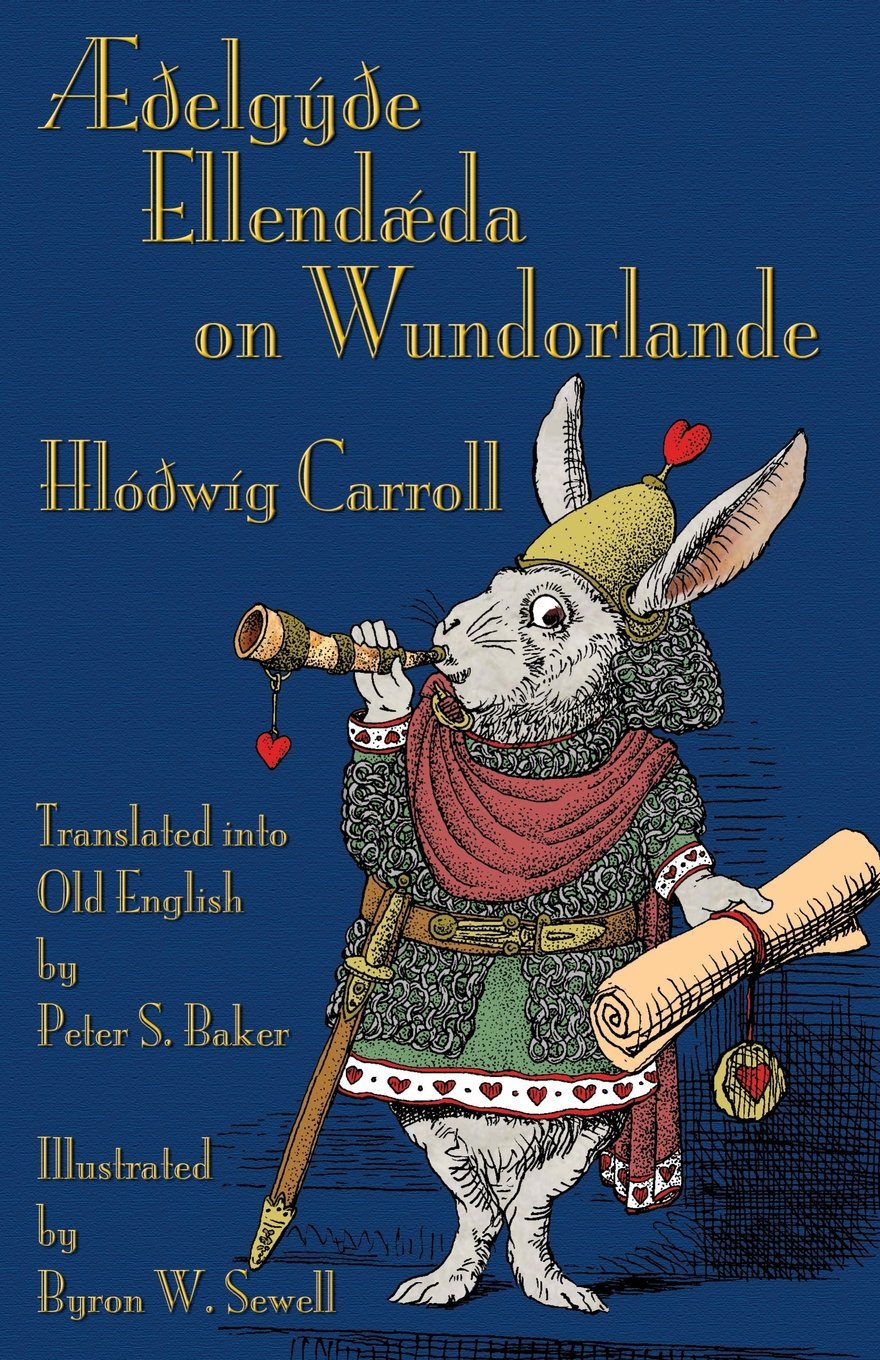

English professor and medieval scholar Peter S. Baker, though, brings a most curious contribution to the table: a translation of “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” into Old English, sometimes called Anglo-Saxon, the language spoken and written in Britain from about A.D. 700 to 1100.

The Challenge of Translating ‘Alice’

Author of one of the literary world’s most widely translated works, Lewis Carroll – the pen name of Charles L. Dodgson – might be surprised “Alice” has fans in many countries, including China. In honor of the sesquicentennial, Jon Lindseth, head of the Lewis Carroll Society of North America, recruited an army of translators a few years ago, including Baker, to contribute to his three-volume “Alice in a World of Wonderlands: The Translations of Lewis Carroll’s Masterpiece.” The collection includes a bibliography of translations and essays about many of them.

Lindseth commissioned translations in several African languages and dozens of obscure English dialects – 174 languages and dialects in all.

Baker, who’s been on the U.Va. faculty since 1992, set his translation in medieval England, so Alice and the other characters in the illustrations are dressed in medieval clothing. The “Mad Tea-Party” becomes a “Mad Beer-Party,” because there was no tea in England at the time; everyone drank beer, even children. Likewise, there were no watches at the time, so the White Rabbit’s watch has become an astrolabe.

Even the name “Alice” didn’t exist in Old English, nor did the word “adventure.” Baker came up with the closest equivalent, Æthelgyth, for the heroine’s name, and for “adventure” he chose “brave deeds,” so the title would be translated as “The Brave Deeds of Æthelgyth in Wonderland.”

“I think ‘brave deeds’ works for Alice. She’s so spunky,” Baker said.

In Lindseth’s collection, the translators also wrote essays on the challenges of the project and provided back-translations to show the differences in languages from different countries and time periods. The before-and-after English versions “illustrate the particular decisions that had to be made,” Baker said.

“A book like ‘Alice’ – full of poetry and puns – is difficult for translators,” he said. “You kill a pun by explaining it. We generally try to replace it with another pun that will work in that language.”

For example, at the Mad Tea-Party, the Hatter sings, “Twinkle, twinkle, little bat, how I wonder what you’re at / Up above the world you fly, like a tea-tray in the sky …” – sound familiar? Anglo-Saxon poetry, however, did not have lines that rhymed, but it repeated consonant sounds, called alliteration, and had four stresses in each line, so Baker wrote his translation in that form.

“Alice” isn’t the only work Baker has translated into Old English. Several years ago, he tried “Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone,” the first volume in the popular series by J.K. Rowling.

“I became interested in translating into Old English after chatting with a student in classics who had read the Harry Potter book in Latin,” said Baker, who got as far as nine chapters before giving up the project for the lack of a publisher. “I learned a lot doing it,” he said.

Fortunately, Lindseth already had a publisher lined up for the “Alice” translations: a small Irish press called Evertype, which specializes in a few arcane topics, along with studies of Dodgson/Carroll, who also was a mathematician and an avid photographer.

“There’s a long tradition of translating popular children’s books into Latin as a way of promoting interest in the language and providing a fun way for people to practice their reading,” Baker said, “but there have been very few such translations into Old English, and these have been of obscure works, or not widely distributed or not terribly well done.”

Perhaps the publicity surrounding the 150th anniversary of “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” will give Baker’s work a boost. The Lewis Carroll Society has set up an exhibit at the Grolier Club in New York City, to which Lindseth said he sent 26 boxes of “Alice” translations. Around the world, at least 14 countries are holding about 100 events to mark the 150th anniversary this fall.

The Challenge of Showing Off ‘Alice’

U.Va.’s Special Collections Library holds more than 1,500 items related to “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” and Dodgson’s other works, including “Through The Looking Glass” and treatises on logic and mathematics.

“The portion of the collection relating to ‘Alice’ is the largest and includes hundreds of editions, as well as parodies, interpretations and re-imaginings of Alice’s adventures from all periods and in many different languages,” head curator Molly Schwartzburg wrote in a blog post about the exhibit.

The bulk of the library’s collection came from the late philosophy professor Peter Heath, who taught at U.Va. from 1962 to 1995. Heath himself published “The Philosopher’s Alice” in 1974, in which he juxtaposes the novel’s text with philosophical commentary on how concepts in logic and philosophy have been distorted in the fantastical worlds Alice encounters.

Working in a student internship program this summer, Swicegood curated the exhibit of “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland,” both to mark the 150th anniversary and in honor of Heath, she said. The Mary and David Harrison Institute of American History, Literature and Culture sponsors the program, which gives undergraduates the opportunity to develop an outreach or research project that promotes the library’s resources to the University community and wider public.

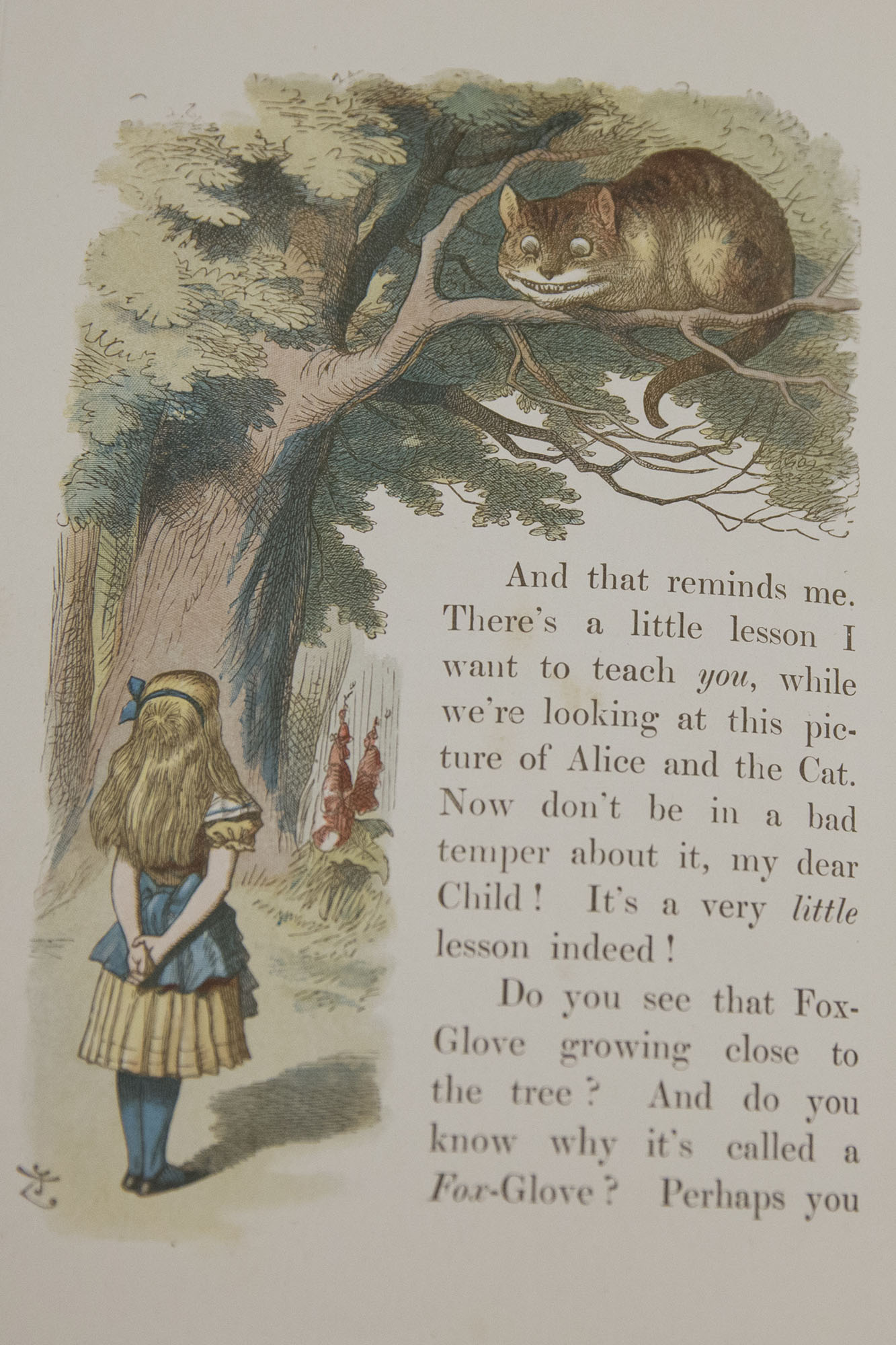

“I decided to focus on illustration since we have so many different illustrators of ‘Alice,’” said Swicegood, an English major who is completing her fifth year in the Curry School of Education’s Master of Teaching program. “I spent about six weeks researching, looking into the publication history and specifically the history of the illustrators.”

Schwartzburg supported Swicegood’s idea. “Faced with the daunting prospect of selecting just a handful of items from the remarkable Heath collection, Susan decided to focus on how illustrators have envisioned the figure of Alice herself over the course of the book’s publishing history,” Schwartzburg said. “She did a beautiful job, and has filled three exhibition cases with items to stimulate memories and artistic inspiration for all generations of ‘Alice’ readers.”

“I wish I could do four more exhibits just on the ‘Alice’ books,” Swicegood added.

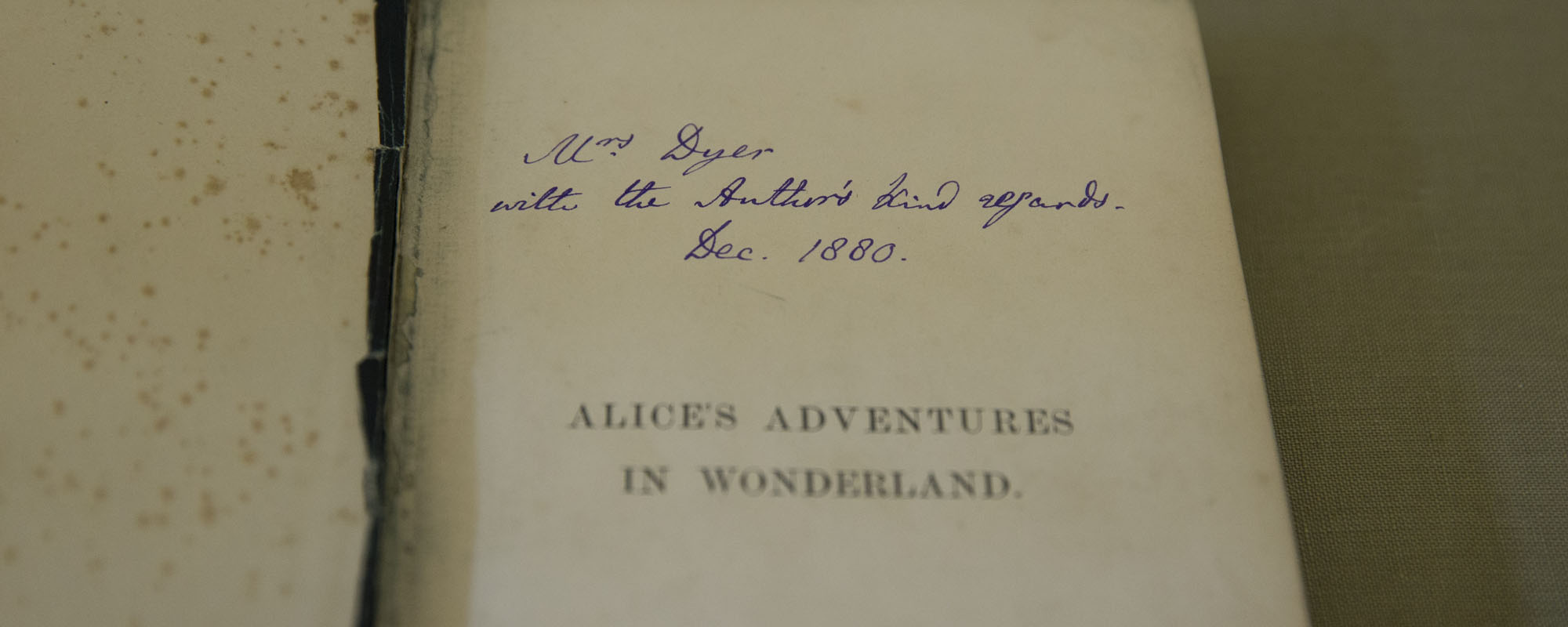

Charles Dodgson, aka Lewis Carroll, signed the copy he gave his landlady in 1880 “with the Author’s kind regards.” It seems he regularly inscribed his books from the “author” rather than choose between his penname and real name, student curator Susan Swic

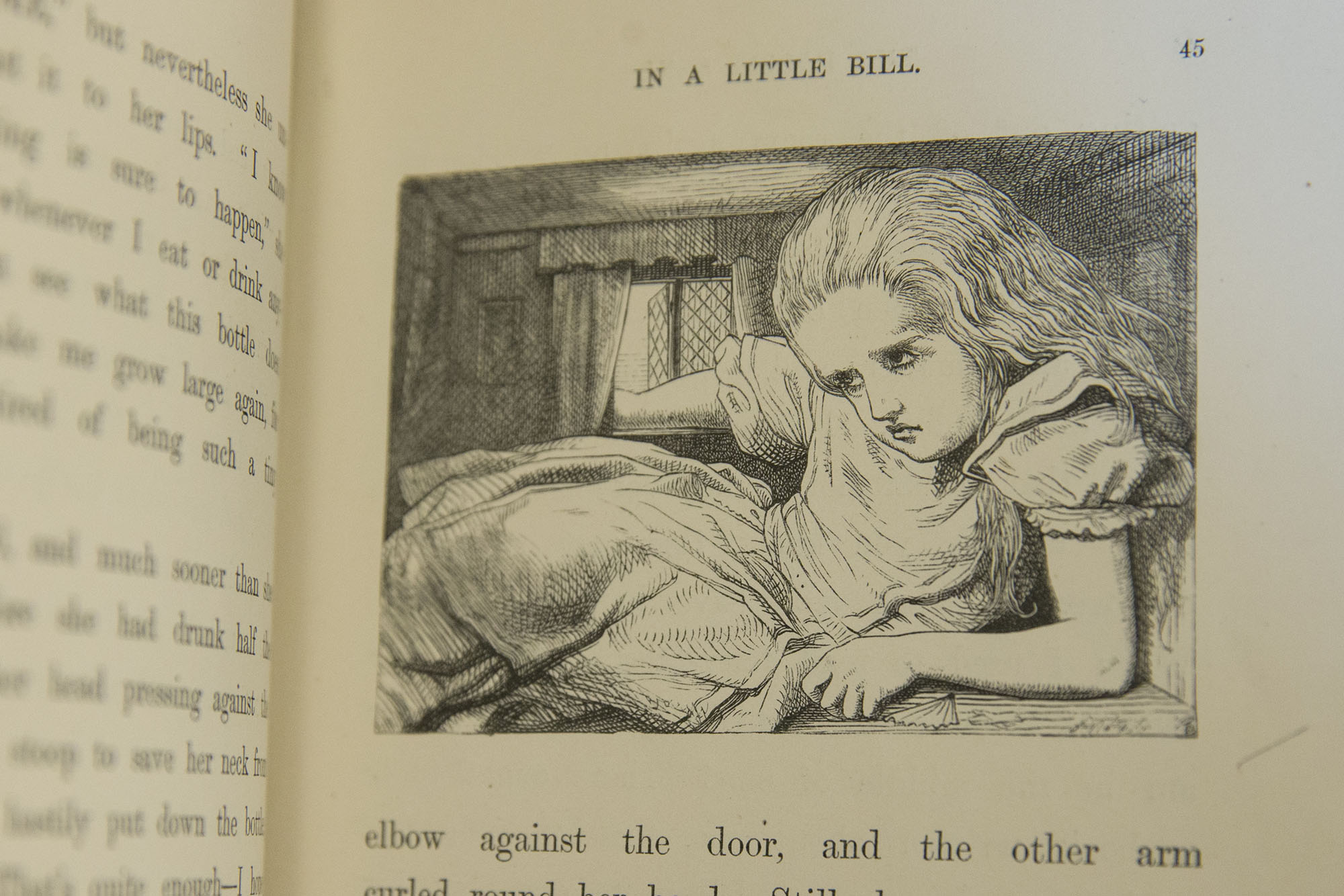

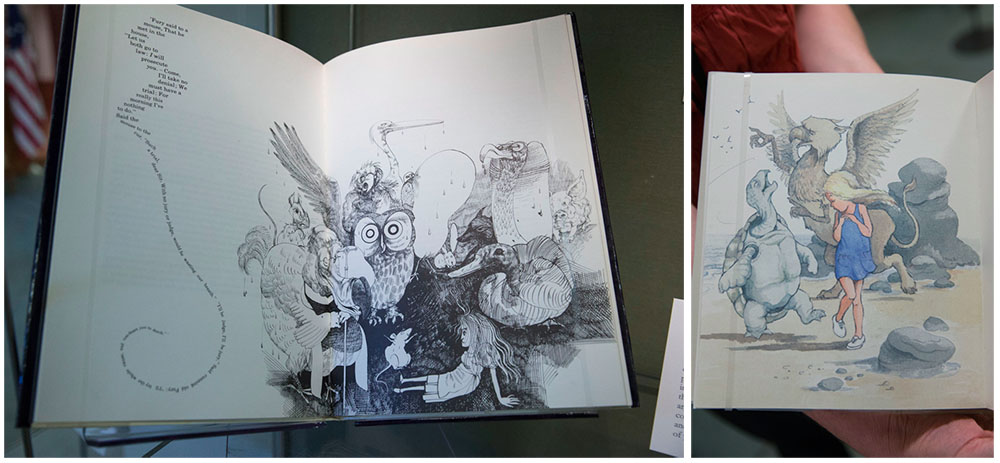

Swicegood organized the exhibit into three sections, showing how the illustrations have changed over time and represent different social eras and developments in printing techniques. The cases display “The Origins of Alice,” with illustrator John Tenniel’s original drawings; examples from the “Golden Age of Illustration,” after the book’s copyright expired; and “An Alice for Every Generation,” depicting how Alice has been reinterpreted by later generations.

What Alice looks like also reflects the times. “From a serious Victorian child, she becomes sweeter,” she said, although not in every case.

Helen Oxenbury’s Alice, right, loses the stiff, frilly dress and sports modern clothes and tennis shoes. The drawings of satirist Ralph Steadman, left, show her as a chaotic, ink-splattered Alice, reflecting the political and social rollercoaster of his e

Swicegood held internships in Special Collections last year as well as this summer, curating an exhibit on juvenile series books from World War I last fall and in the spring, an exhibit on Harriet Beecher Stowe’s influential novel, “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.”

She’s even considering pursuing another master’s degree, in library science, to combine education with library work.

Media Contact

Article Information

September 2, 2015

/content/uva-joins-celebration-alice-150-even-old-english