To a colleague in the University of Virginia’s Corcoran Department of History, professor Claudrena Harold mentioned one day that she was researching the experiences of African-American students who attended UVA in the 1970s.

Kent Merritt looked at Harold. “Then he sort of nonchalantly said, ‘You know, I was here during that time,’” Harold recalled.

“I was like, ‘What?’ And then slowly but surely it began. He’s not a boastful person. You have to ask Kent 100 questions to really figure out his historical importance,” she said.

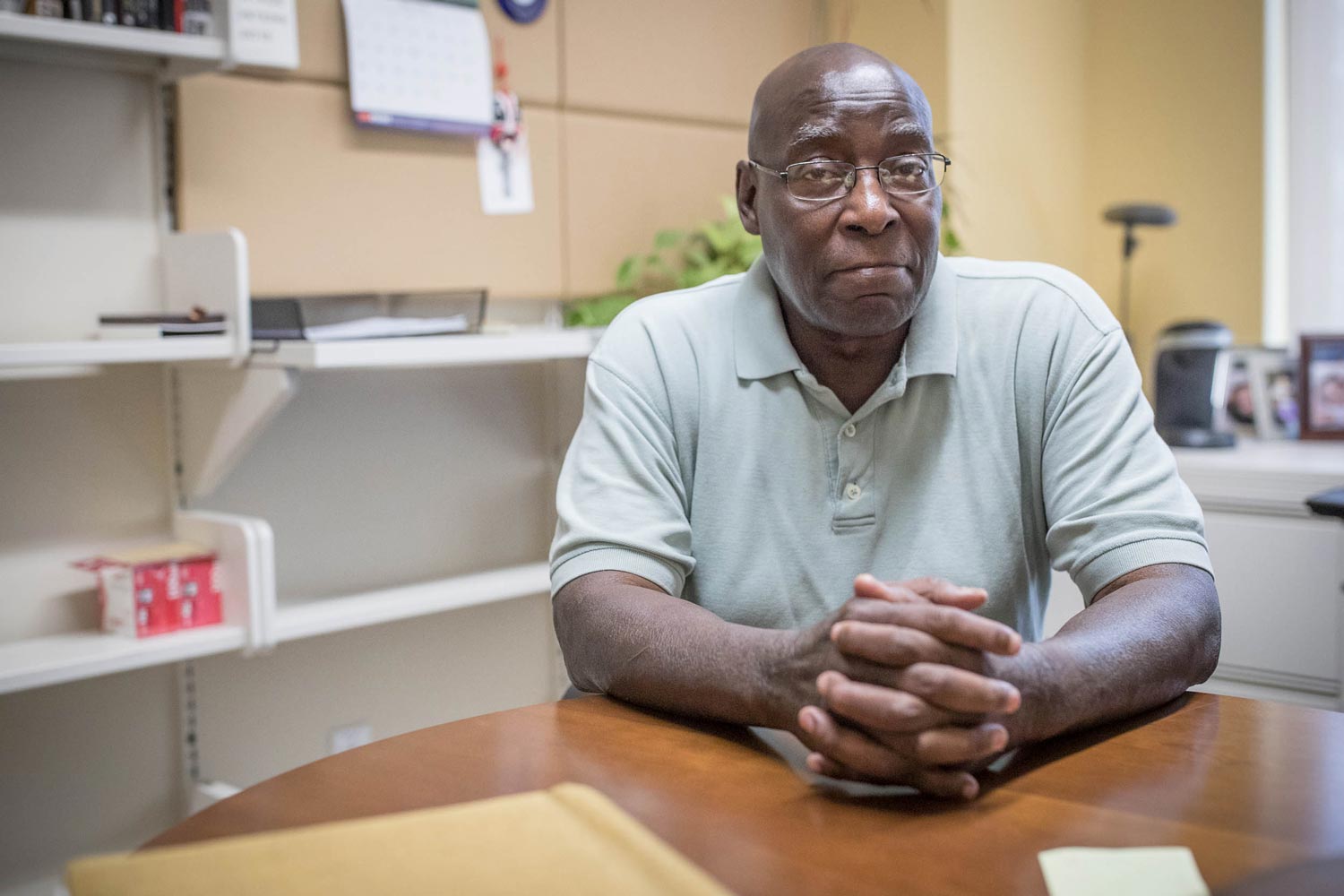

Merritt, who returned to UVA in the early 2000s after two decades in the banking industry, is retiring next month. As administrative supervisor, he’s “critical to the financial operations of the [history] department,” Harold said. “He’s the person you go to to figure out what you can and you can’t do.”

That’s only part of his story. Long before he came back to work at his alma mater, Merritt was a pioneer at the University.

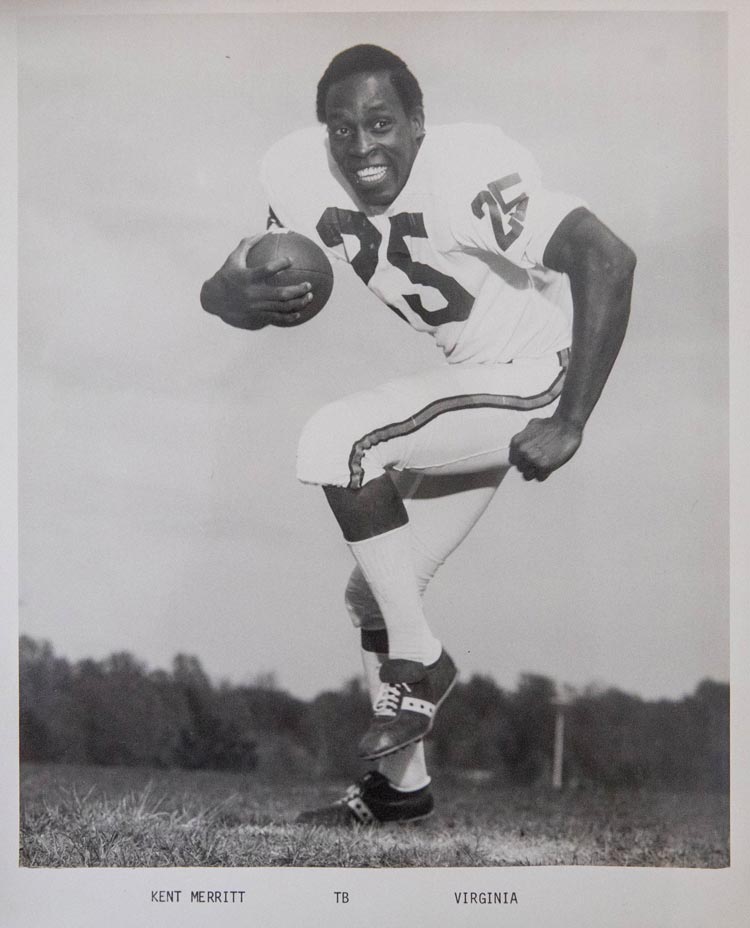

In 1970, he was one of the four black scholarship student-athletes, along with Harrison Davis, Stanley Land and John Rainey, who integrated the Cavaliers’ football team. (Also that year, Al Drummond became the first African-American scholarship student-athlete to join the UVA men’s basketball team.)

In 1970, Merritt became one of the first four African-American football players at UVA.

“My whole life has been firsts in a lot of areas,” Merritt said in his Nau Hall office.

Merritt, 66, has two degrees from UVA: a bachelor’s in economics and an MBA from the Darden School of Business. Had he had his way, though, he might have left his hometown and attended college elsewhere.

At Charlottesville’s Lane High School, where he became the first African-American class president, Merritt dazzled in football and track and field and excelled as a student. His football skills earned him scholarship offers from such schools as Penn State University, the University of North Carolina, the University of Tennessee, the University of Notre Dame, Virginia Tech, Clemson University and the University of South Carolina.

Virginia wanted him too, however, and “there was a lot of pressure locally to come here,” Merritt said.

His mother had worked at the University as a nurse, and his father was employed at UVA at the Judge Advocate General’s Legal Center and School.

“Virginia had no black players then,” Merritt said, “and one of the reasons they said they did not have any black players was that they couldn’t find players of color who had the academic wherewithal as well as the athletic ability, that combination, to come here.

Merritt, the first black class president in Lane High School history, chose UVA over multiple football suitors.

“But I was a good student, I was president of my class, and I was a good athlete, and I was right here in the backyard, and everybody had seen me play at Lane High School for a number of years and seen me run track and everything, so there was a real push to get me to come here.”

His decision to become a Cavalier delighted his parents. Did they nudge him toward UVA?

“They kind of shoved me,” Merritt said, laughing.

His athletic feats at Lane High School were the stuff of legend. In football, Merritt played for head coach Tommy Theodose in one of the state’s premier programs.

“When you grew up in Charlottesville and you played football, you wanted to be a Lane Black Knight,” recalled UVA alumnus David Sloan.

Sloan, an outstanding athlete himself, was three grades behind Merritt at Lane. He hasn’t forgotten Merritt’s high school heroics.

“My dad used to take us to every game, home and away,” said Sloan, who played with Merritt at UVA in 1973.

“I remember one of the games in Richmond. Kent was so damn fast that when he ran a sweep against Highland Springs and he got to the 50-yard line, he [ran untouched to the end zone].”

Off the field, “Kent was a cerebral dude,” Sloan said.

Merritt played on an integrated football team at Lane High, and he credits Theodose for “[keeping] that team together amid all that racial strife that existed at that time.”

By then, Merritt had felt the sting of racism. Before the third grade, he’d moved from the all-black Jefferson Elementary to Venable Elementary, which had been integrated two years earlier.

Every Wednesday, Merritt recalls, Venable students would gather after school at Terrace Bowl for duckpin bowling. When he tried to go one day, a bus driver refused to allow him to board the vehicle.

After a white student got on the bus, Merritt tried to follow suit, and “the guy slammed the door in my face. That was my first brush with discrimination, and it will always stand out.”

At UVA, he became part of a student body with only several hundred African-Americans. In football, Virginia was the last school in the Atlantic Coast Conference to integrate. Not surprisingly, Merritt, Land, Rainey and Davis spent much of their time together.

“I visited other schools, and they were further along in integration and being used to having people of color on their grounds than they were here at UVA,” Merritt said. “But one of the advantages for me, and for my friends, was that being from Charlottesville, I was able to have outlets outside of the University that helped.

“My parents were here. We could go to the house and hang out over there. So we had those outlets, and of course having gone to Lane High School, I knew people here, so it was easier for the four of us to get out and kind of get away from some of the frustrations, as opposed to some of the other [African-American students] who were from elsewhere.”

Under NCAA rules, freshmen were not eligible to compete when Merritt enrolled at UVA. That first fall, he played on the Cavaliers’ freshman team, whose head coach was Al Groh.

Groh, who later spent nine seasons as Virginia’s head coach, has warm memories of working with Merritt.

“Very bright, very purposeful, no-nonsense and very diligent in going about whatever he had to do,” Groh said. “That certainly has manifested itself in the successful careers he’s had following his football career.

“As a football player, he was fast and tough. A lot of times those two things don’t go together. But he was as aggressive running the inside trap as he was running the toss play outside.

“The third thing is, as serious and purposeful as Kent was, he’s always had a terrific smile. He was purposeful, but he was also fun to be around.”

The transition from high school to college – on and off the field – tests many freshmen (or first-year students, as UVA calls them). For Merritt, Land, Rainey and Davis, the challenge was greater.

“I was certainly alert to the fact that these four kids had an enormously different adjustment to make than the other kids on the team,” Groh said. “They handled everything beautifully. We’re very proud of the four of them.”

Merritt and his classmates moved up to the varsity in 1971, Don Lawrence’s first season as the Wahoos’ head coach. Lawrence had taken over for George Blackburn, the coach who recruited the class that included Merritt, Rainey, Davis and Land.

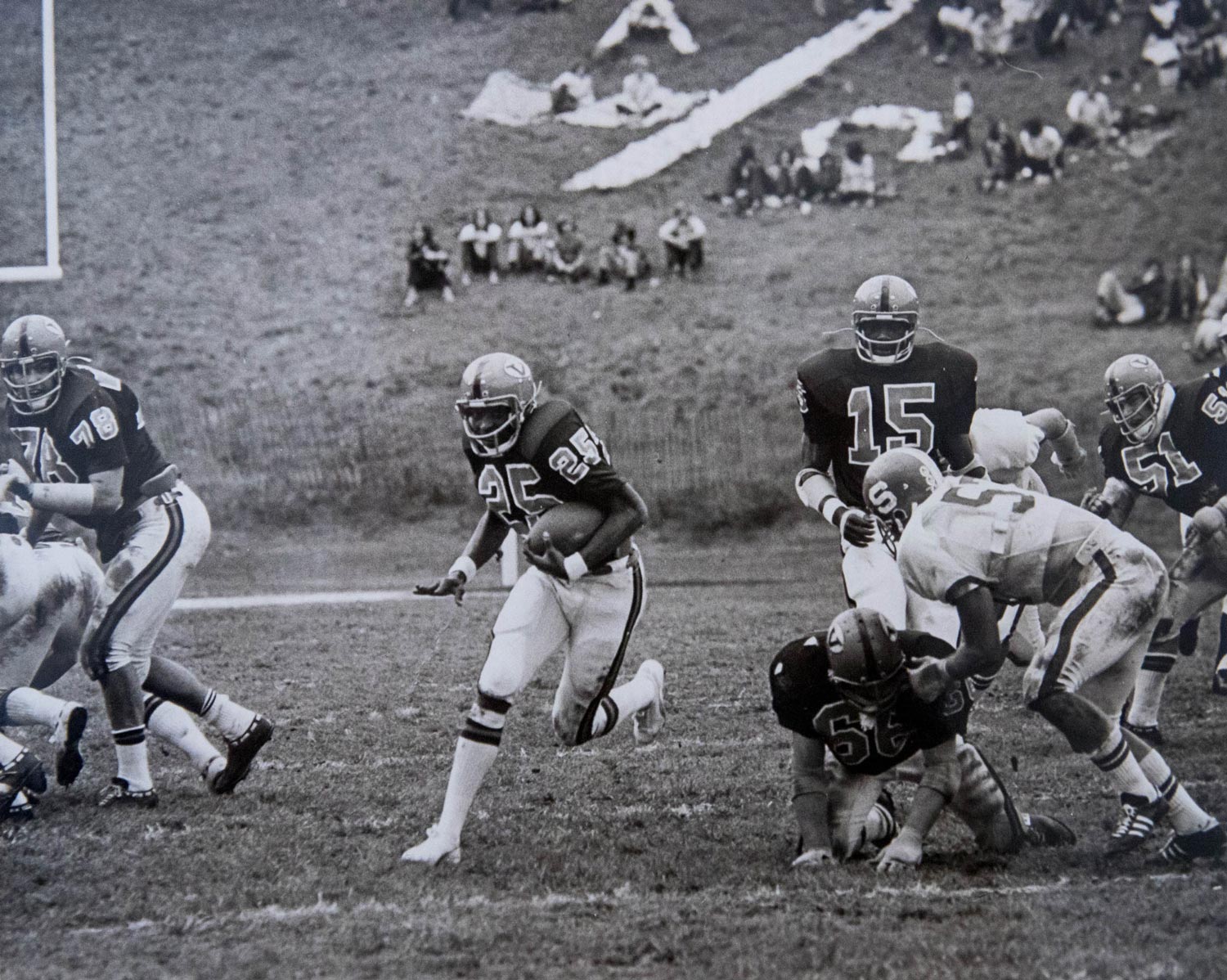

On teams that finished 3-8, 4-7 and 4-7, respectively, Merritt lettered each season. He led the ’Hoos in rushing and all-purpose yards in 1971 and ’72. As a junior, he also averaged 22.7 yards per kickoff return.

The racial dynamic on the team wasn’t always positive for Merritt and his fellow African-Americans, he said.

“Some of the [other players] didn’t like our presence,” Merritt said. “I know that there was some resentment with Harrison being the quarterback, and some of it was racial, and some of it was simply because he was replacing a guy who’d been there, Bill Troup, who was part of the gang.

“It was controversial. ... I didn’t get a lot of it, simply because I wasn’t the quarterback, but I did get some, because I replaced a guy [at tailback] who was well-liked, Jimmy Lacey. But the fact of the matter was I was a better back than him. I just was.

“It wasn’t blatant, and racism isn’t [always] blatant. But it was definitely there. Eventually I think we gained more respect, because we were the playmakers.”

The atmosphere at Scott Stadium wasn’t especially welcoming for African-American players, Merritt said, “because they still had the Rebel flag, and they’d wave it around after touchdowns, and they played ‘Dixie’ and all that kind of good stuff, and they didn’t do that at other places. But as far as just actual nastiness on the football field, that was rare. Because you’re playing football, and that’s a different type of fraternity among players.

“Now, I understand there were a lot of comments made in the stands, but that’s not something that we actually heard on the field. I remember a guy telling me that on one play I went out and dropped a pass, and somebody [in the stands] yelled, ‘Throw him a watermelon, he’ll catch that.’ That type of thing.”

The atmosphere surrounding athletics in the early ’70s was much more apathetic than today. “They kind of saw it as being quote-unquote State U-ism, and that was not desirable in an academic institution,” Merritt said.

Around Grounds, Merritt said, he and his black teammates didn’t sense much resentment from their fellow students.

“But I think because we were athletes, we had it easier,” he said. “You’re accepted more, because you have a talent, and people want to be associated with talented people. That’s all there is to it.”

Several years ago, during a Black Student Alliance symposium at UVA, Merritt discussed his undergraduate experience. Others on the panel with Merritt included Akil Mitchell, a forward on the Virginia men’s basketball team through 2014.

“I can relate to the things he went through,” Mitchell said recently. “To understand he did them at a time when he was one of the first [African-American student-athletes at UVA], I don’t know if I would have had the courage or patience to do any of them. It was pretty inspiring.”

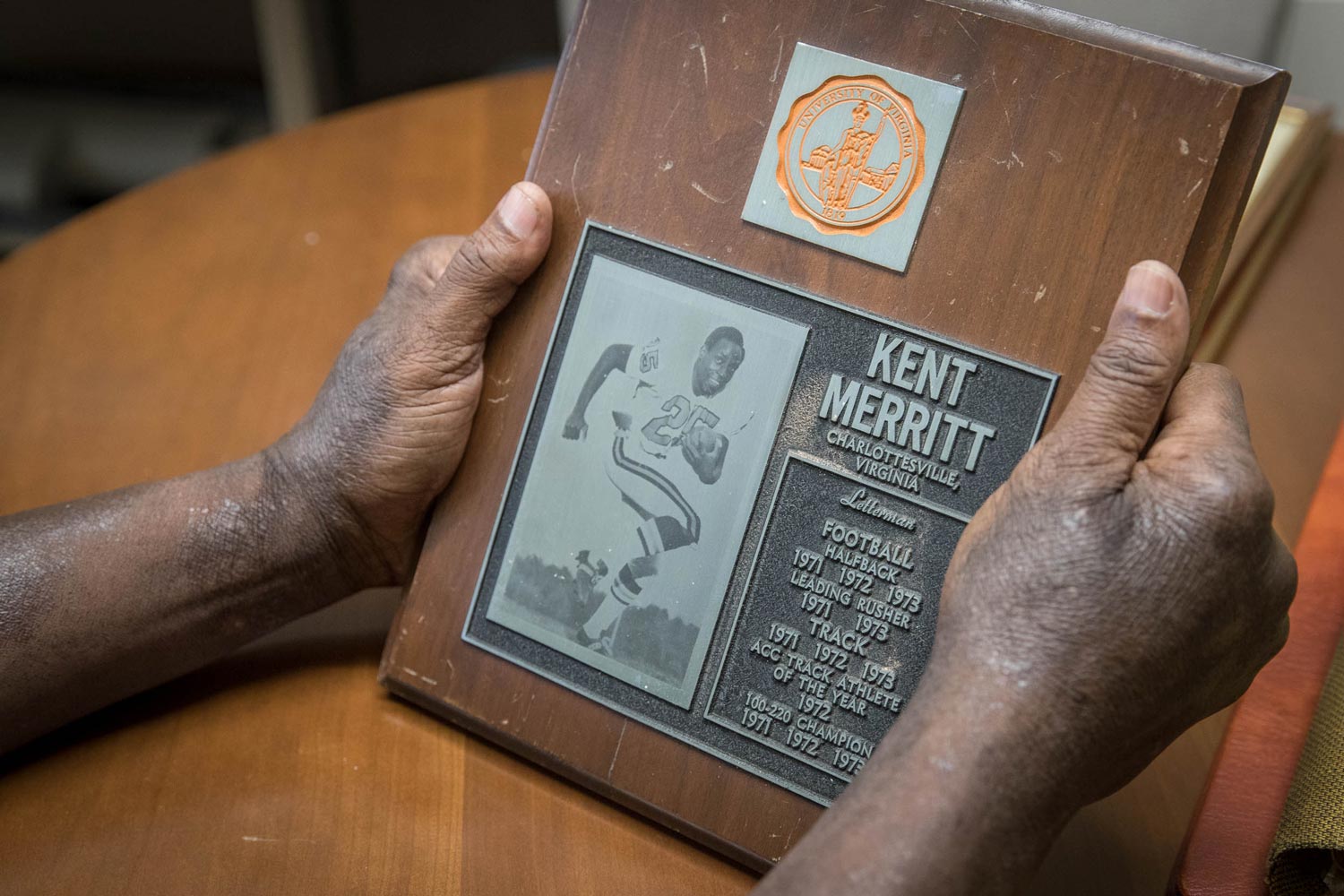

As soon as football season ended each fall, Merritt joined the track team at UVA. He won six ACC titles in that sport, capturing the 60-yard dash (indoors) in 1972 and ’73; the 100-yard dash (outdoors) in 1971, ’72 and ’73; and the 220-yard dash (outdoors) in 1972.

In outdoor track, Merritt was named ACC performer of the year in 1972.

In addition to his success on the football field, Merritt was a standout track athlete. (Photo by Sanjay Suchak, University Communications)

In his office, Merritt has a Sports Illustrated article that includes a photo taken at a track meet at the University of Maryland. Also pictured are Delano Meriwether, Ivory Crockett, Mel Pender and Don Quarrie, and “those were the top sprinters in the world at that time,” Merritt said.

“I had some wonderful experiences [in track], meeting people like that and running against them and going all over the country.”

Claudrena Harold, who played basketball at Temple, joined the history faculty at UVA in 2004. In recent years, she’s been involved with numerous projects exploring the history of African-Americans at UVA. One was an experimental film she made with Kevin Everson, “Fastest Man in the State” that focuses on the experiences of Merritt, as well as those of Rainey, Land and Davis.

“On numerous occasions, my students have gone to Kent seeking information for their group projects,” Harold said. “He has always been welcoming and willing to assist the students in any way he can. ... To watch the intergenerational exchange between Kent and the younger students, it’s awesome.”

Merritt also has been an invaluable resource for Harold, who teaches a lecture course titled “Black Fire,” which examines the history of African-Americans at UVA since 1964.

“His knowledge of Charlottesville, his knowledge of Vinegar Hill, his knowledge of the African-American community, his knowledge of the changing nature of the black middle class [are priceless],” Harold said. “It’s like if there’s a [new] book written on African-Americans at the University of Virginia, he has to be consulted. He has to be a part of that book. His knowledge is just deep.”

Athletics was not the only endeavor in which Merritt was a trailblazer at UVA. As a fourth-year student, he helped establish the Eta Sigma chapter of the Kappa Alpha Psi fraternity at the University. The seven other charter members included Davis, with whom Merritt lived every year as a UVA undergraduate.

Merritt and his fraternity brothers helped “lay important foundations for African-American life at the University,” Harold said.

“When you think about a group like the Kappas, they’ve now celebrated their 40th anniversary on Grounds. So I think it’s important to talk not only about African-Americans integrating the University, but also how they changed the social and intellectual fabric of the University.

“People like Kent came here in the early 1970s, when there was nothing, when there were not certain traditions. They helped build those traditions, and they are the traditions that current black students turn to and build on and nurture and nourish.”

In 1974, Merritt tried out for the New Orleans Saints, who had drafted him in the 11th round. (The San Diego Chargers picked Davis in the fourth round that year.)

His NFL dream ended when the Saints cut him during training camp. Merritt came back to Charlottesville and took a job with the National Bank and Trust Company.

He later worked in banking in North Carolina – first in Raleigh, and then in Havelock – before returning to Charlottesville. After another year at National Bank, Merritt enrolled at Darden, from which he graduated in 1983.

“Then I went back into banking,” Merritt said, laughing.

His post-Darden career took him first to Charlotte, N.C., and then to the Washington, D.C., area before Merritt returned to his alma mater. He worked first in UVA’s anthropology department before moving to history.

In April, the UVA Alumni Association honored Merritt with its 2018 Distinguished Service Award.

“This is the job I should have had: a career in education,” Merritt said. “Period. This is where I fit best, I think.”

He’s remained close with Davis, Rainey and Land, who live in Florida, Maryland and Texas, respectively. They still get together for a UVA football game each year.

In Merritt’s office is a framed photo of the four of them with Groh, who said he has the same picture.

As an administrator in the history department, Merritt has been a valuable resource to faculty and students alike. “His knowledge is just deep,” history professor Claudrena Harold said. (Photo by Sanjay Suchak, University Communications)

Merritt follows UVA sports and attends football games at Scott Stadium periodically.

“The attitude certainly has changed toward athletics [at UVA], big time,” he said. “When I got here, you really didn’t have a whole lot of support for athletics among the student body or the faculty. They kind of saw it as being quote-unquote State U-ism, and that was not desirable in an academic institution. But people are gung-ho now. If the [men’s] basketball team loses five games, people are really upset.”

Merritt, whose son lives down the street from him in Charlottesville, has four grandchildren, and he’s eager to spend more time with them. His plan for retirement?

“Relax,” Merritt said, laughing.

Media Contact

Article Information

May 22, 2018

/content/uva-pioneer-ready-next-chapter