What if smartphones could alert you or your physician to a medical problem? Or even monitor your progress after you had suffered a concussion?

A University of Virginia research team, in collaboration with Lockheed Martin Corp., is developing smartphone applications that can identify symptoms of infectious disease and traumatic brain injury by monitoring a user’s daily activities.

“After you experience a concussion, can we see patterns of behavior changes as you go about your daily life that would indicate you are recovering or getting worse?” said Laura Barnes, a UVA associate professor in the Department of Engineering Systems and Environment, where a dozen faculty members focus on health care systems research. “Can we use everyday devices people carry, like their smartphones and smartwatches, to identify these changes? We are ultimately looking for objective, quantifiable, digital biomarkers of disease. Sensors already embedded in smartphones – including light, microphone, pedometers, GPS, to name a few – have the potential to provide these markers.

Laura Barnes is an associate professor in the Department of Engineering Systems and Environment, where a dozen faculty members focus on health care systems research.

“We are looking to see if these technology-based markers could potentially indicate that you are getting sick or already sick, and if so, the severity of the illness.”

The federal Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, or DARPA, is contributing about $2 million for the University’s portion of the research. The project, “Reliable Analytics for Disease Indicators,” or ReADI, has researchers developing software for mobile systems to detect anomalies in a subject’s health.

To develop and test the software, the UVA researchers have engaged almost 200 students, about 80 of whom are athletes, as subjects. The researchers first build a baseline on the students – how well they sleep, how much sleep they usually get, their exercise and exertion habits, how they walk – so the algorithm can detect deviations from the student’s normal behavior.

Once baseline data is collected, individuals install a smartphone app called ReadiSens, available in the iOS and Android stores, that collects passive digital indicators of health. Subjects also complete periodic surveys on their smartphones about health and health-related behaviors, such as symptoms, physical activity, sleep and health.

The hope is that researchers can use the data collected in this study to develop algorithms for continuous and real-time assessment of health.

“In the beginning it had a lot of surveys when I first woke up or when I changed position,” said Erika Osherow, a fifth-year graduate student majoring in kinesiology who volunteered as a subject. “I feel like it picked up when I was moving faster or doing something different, because it would ask me what I was just doing.”

Osherow, a former UVA softball player who sustained concussions in high school, said she joined the project to support her professors.

“I love enhancing research, and having [had] concussions myself and now being healthy, I think there are a lot of interesting and exciting ways to navigate the whole recovery process,” she said.

Researcher Jacob Resch, an assistant professor of kinesiology, said the application could help detect concussions – even if the subject is unaware because they do not understand the severity of the injury.

“With a concussion, we know that the quicker an individual gets treatment, the better their outcome, by which I mean a quicker recovery,” Resch said. “So monitoring a subject’s behavior, particularly following a concussion, is really important, because up to 80% of concussions go undiagnosed.

“If a phone, a device that they carry with them on a daily basis, is able to detect abnormalities in behavior and potentially identify some kind of signal that would associate with a concussion, then that could markedly improve recovery time.”

Mehdi Boukhechba, an assistant professor in the Department of Engineering Systems and Environment, said the team is collecting raw sensor data from smartphones and translating it to digital markers, or observable behaviors, of symptoms related to disease and injury.

“The goal is to take these digital behavioral markers and develop models to predict disease state,” Boukhechba said. “To do this, we are working with Lockheed Martin to design the ReADISens smartphone applications for Android and iOS that continuously collect data in an energy-efficient way. Data is collected from multiple sensors embedded in our smartphones, such as GPS, accelerometer, temperature and audio. Because this data is big, noisy and complex, we are building cutting-edge algorithms to turn those sensor signals into meaningful information.”

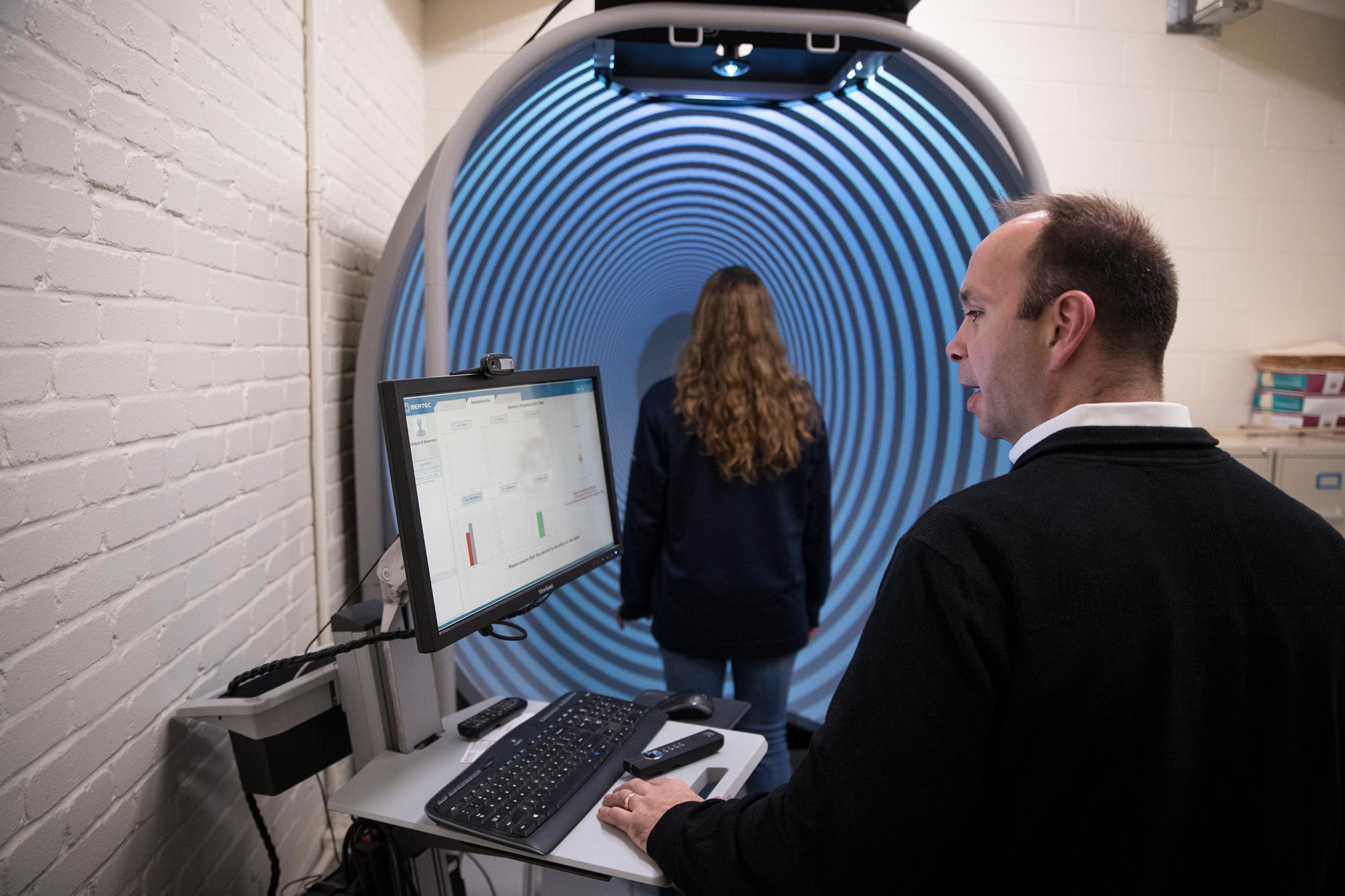

Researcher Jacob Resch, an assistant professor of kinesiology, studies Erika Osherow’s balance for the ReADI project.

ReadiSens is based on the Sensus open-source smartphone application, developed at UVA. “Sensus is fully customizable mobile sensing system that alleviates technical burdens for researchers who wish to leverage mobile technologies for human-subject studies,” Boukhechba said.

The researchers are working closely with mobile application developers at UVA ITS-Custom Applications and Counsulting Services to customize Sensus for the development of the app, embedding artificial intelligence and optimizing battery life.

Barnes said Sensus was originally developed to study human behavior in natural settings, because there is a large learning curve and cost for researchers who want to research in that field.

“Studying individuals in the wild, meaning outside of the lab or a clinical environment – we have a better shot at understanding health and health-related behaviors in unprecedented ways that we could not before these sorts of technologies existed,” she said.

Dr. Rebecca Dillingham of UVA’s Center for Global Health said the application has potential in recognizing and controlling infectious diseases.

“If early warning of the spread of infectious conditions, such as influenza, could be collected through smartphones, better advice could be given to individuals who have the symptoms, such as suggesting that they stay home – or seek medical attention, if severe,” Dillingham said. “It could also help to control outbreaks at a population level by helping people who are infected to avoid spreading the germs causing their illness. This may be particularly important on college campuses, in military camps and other places where people live in close association.”

Dillingham said the proper mobile application can also help people who live with chronic conditions, helping them monitor and achieve their health goals. The technology can be directed to alert a caregiver or simply make the user more aware of his or her behavior and potential risk.

Osherow, who plans to be a sports psychologist, said she likes the application because it can influence performance.

“It relates to what motivates people, how to balance social life with academics and sports, what drives people to continue doing what they want to do, what they love to do and how to get people to want to exercise,” she said. “I think there is so much that can be harnessed in people. I think everybody has motivation. It is just harnessing it in people, how to optimize performances, how to optimize mindsets.”

Barnes sees many more opportunities for the technology in the future.

“There is a lot of potential for considering how this technology could be used in practice. It could be monitored by a clinical team or it could be just be a self-monitoring tool to make individuals more aware of their health,” Barnes said. “Right now, we are not doing anything like that. We are just developing the technology, but I think the sky is the limit in terms of how this would be used in practice.”

Media Contact

Article Information

February 6, 2020

/content/uva-researchers-does-my-smartphone-know-i-am-sick