College students living off campus often report little or no income, causing them to inflate the poverty rates of college towns, according to University of Virginia researchers in the Weldon Cooper Center for Public Service’s Demographics Research Group. Smaller localities hosting large universities have some of the state’s highest poverty rates.

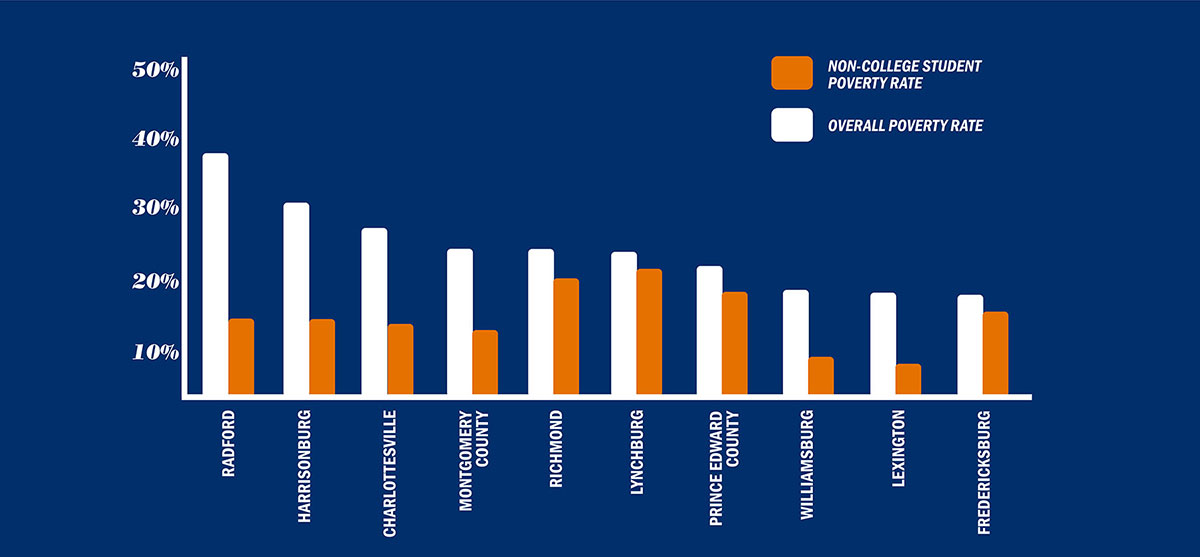

The city of Radford leads the list, with a total poverty rate of 40 percent. Radford’s rate without students, however, is 15 percent, closer to the statewide poverty rate of 12 percent. Similarly, Harrisonburg’s poverty rate goes from 33 percent to 15 percent when students are removed from the calculation. Charlottesville’s rate declines from 28 percent to 15 percent, while Montgomery County’s declines from 26 percent to 13 percent.

“Cities and counties home to large colleges or universities need to be clear about the non-student poverty rate in their localities,” said Luke Juday, a research and policy analyst for the Cooper Center and co-author of the census brief, “Poverty in College Towns.” “Students in poverty generally do not have the same chronic employment and economic problems of other groups in poverty, and are not usually helped by services targeted toward those groups.”

Cooper Center researchers applied a methodology suggested by the U.S. Census Bureau for removing students from a locality’s poverty rate.

In the graph above, the white columns show the overall poverty rates in 10 of Virginia’s localities. The orange columns show the poverty rates when off-campus college students are excluded from the tally.

“While some students live below the poverty line, their poverty is generally understood to differ from intergenerational poverty for two reasons,” observed Annie Rorem, also a research and policy analyst for the Cooper Center and co-author of the center’s brief. “Students may have access to resources outside their incomes, and student poverty tends to be a temporary experience entered into voluntarily in order to improve earnings later in life.”

However, in some localities with large universities, removing students from the poverty rate calculations does not affect the poverty rate significantly, suggesting that these localities face real intergenerational poverty.

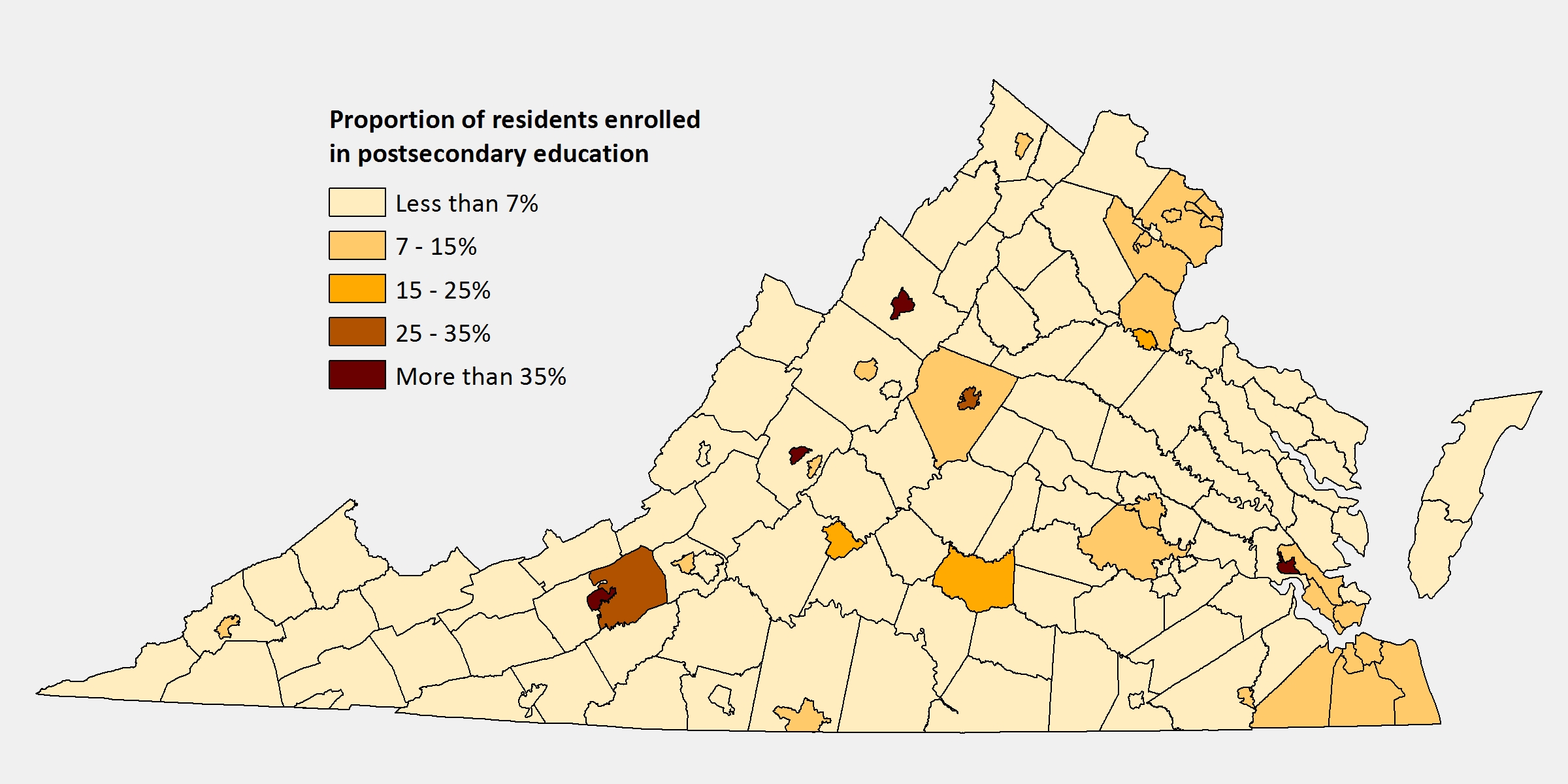

The above map shows the percentage of residents enrolled in postsecondary education by locality.

“For many years, leaders in localities home to colleges and universities have known that official poverty rates may not be an accurate reflection of the economic conditions of their non-student residents,” said Qian Cai, director of the Demographics Research Group. “We are pleased to offer a cleaner measure for local officials to better understand the needs in their communities.”

The center’s full census brief is available here.

Media Contact

U.Va. Weldon Cooper Center for Public Service

meredith.gunter@virginia.edu 434-982-5585

Article Information

March 4, 2016

/content/uva-study-college-students-skew-small-town-poverty-rates