History Lessons

This month brings the 50th anniversary of the break-in of the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee at the Watergate office complex in Washington, D.C., the scandal that took down President Richard Nixon, who resigned in disgrace in 1974. It was a challenging time for democracy.

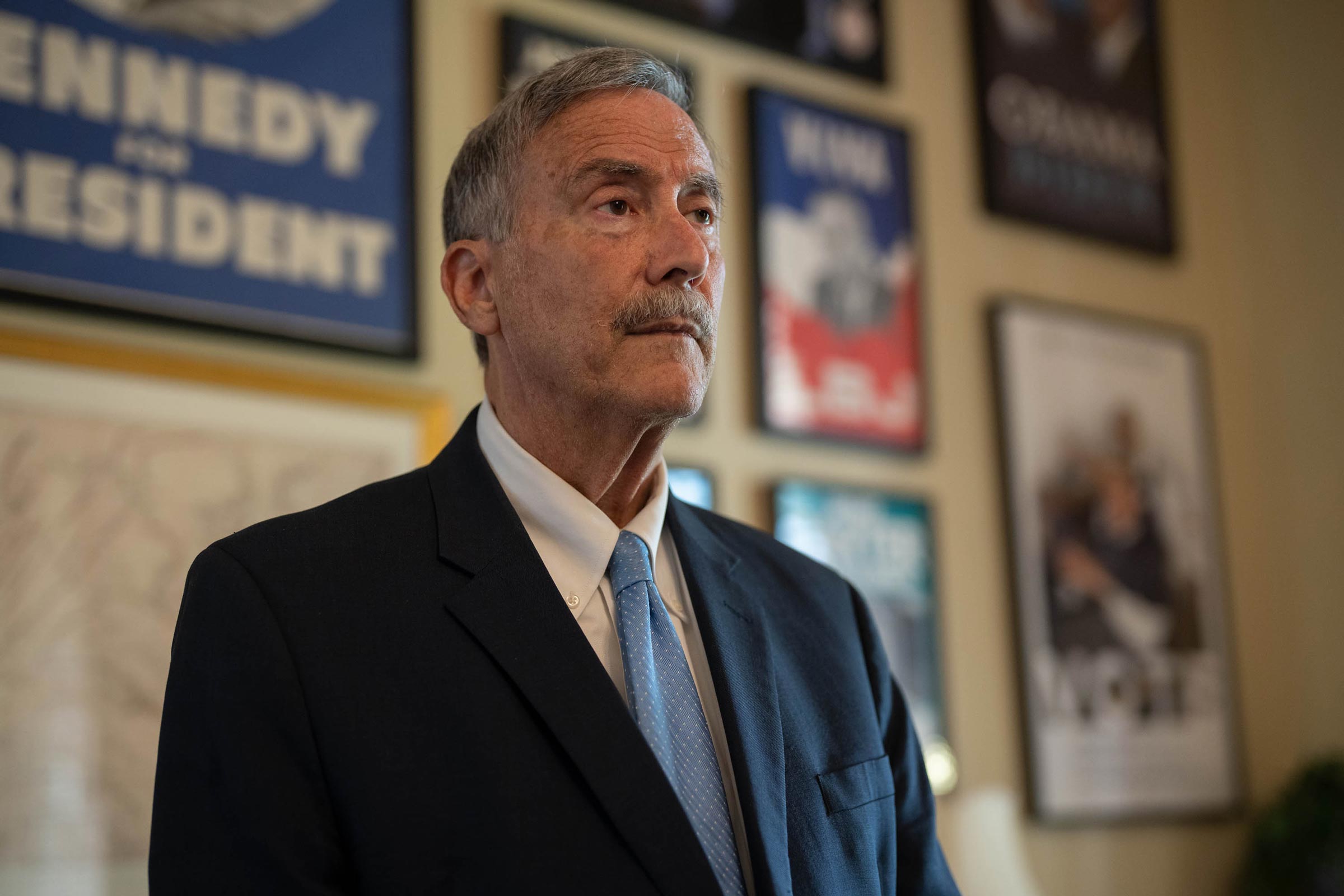

Sabato could teach a class solely on the politics around Watergate, but in the context of today’s discussion he looks back further at the Nixon story to point out something relevant now.

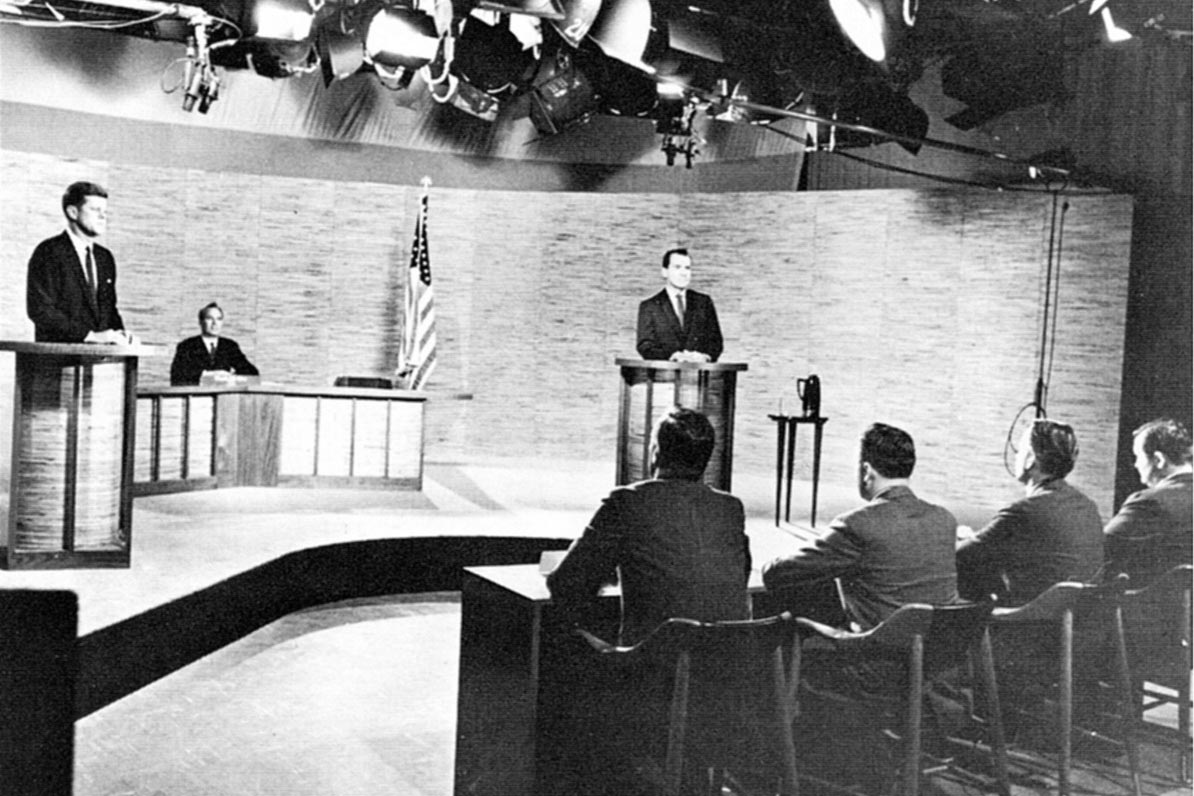

In the 1960 presidential race, John F. Kennedy beat Nixon by 112,827 votes, or only 0.17%. Kennedy won Texas (home of running mate Lyndon Johnson) by just 46,000 votes. He won Illinois by fewer than 9,000. The two states were pivotal given the number of Electoral College votes at stake. With margins so slim, allegations of voting fraud emerged.

Nixon, who served as Dwight Eisenhower’s vice president, gathered with his supporters in Los Angeles on Nov. 9, 1960 – the day after Election Day. He acknowledged that votes remained to be counted, but the momentum was with his opponent.

“I want to say that one of the great features of America is that we have political contests. That they are very hard-fought, as this one was hard fought, and once the decision is made, we unite behind the man who is elected,” Nixon told the audience.

A peaceful transition – not perfect, but peaceful.

“People can say all they want about Nixon. And we all know his flaws,” Sabato says. “But in 1960, because our system was built around the principle that the loser concedes to the winner, even if there are doubts about Illinois or Texas, you do the right thing. And Nixon did it. He was bitter on account of it, and in some ways it led to Watergate. But he did it.”

As did Al Gore in 2000, conceding to George W. Bush, who lost the popular vote but won the presidency in the Electoral College in a race famous for controversies in decisive Florida and a Supreme Court ruling that ended the recount process there.

“Other disputes have dragged on for weeks before reaching resolution,” Gore said in his concession. “And each time, both the victor and the vanquished have accepted the result peacefully and in a spirit of reconciliation. So let it be with us.”

Given the violent efforts on Jan. 6, 2021, to derail Congress’ responsibility to certify the 2020 presidential election, I ask Sabato if he thinks people today take democracy for granted or if they just don’t consider it all that important.

“People care about democracy,” he answers. “And they want to keep a democracy – as long as they get their way. A critical factor in a democracy is accepting when you lose, accepting the legitimacy of the winner. We’ve lost that, or at least millions of people have lost the ability to do that.”

Of course, Nixon isn’t famous for being magnanimous. He’s famous for political corruption laid bare for all to eventually hear in the secret Oval Office recordings that took him down.

“We should remember that if Nixon had not taped himself, odds are good that he would have finished his term,” Sabato points out. “Good luck has played a role in rescuing the country in many of our crises. We shouldn’t depend on luck to save us.

“Choosing a higher quality of elected official, when we have the opportunity, would help, and better civic education – which is what we emphasize at the Center for Politics – is critical, too,” Sabato continues. “We need people in office who want to solve problems in practical ways, not people who want to posture and inflame the situation further. Partisanship has become extreme now, and the two most powerful letters in the alphabet are D and R. This isn’t good for the nation.”

News and Views

A news and politics junkie since his days growing up in Norfolk, Sabato recalls the family routine of watching and discussing local and national news over dinner after his father returned home from work. Nuncy Joseph Sabato served in the Army-Navy Signal Corps from 1941 to 1945 and worked as a civilian for the Department of the Navy into the 1970s.

Today, Larry Sabato’s news intake begins as early as 5:30 a.m. and continues through his waking hours. The days of heading out in the morning to gather print newspapers are gone. He uses an iPad now. The information flows constantly – from traditional papers, web-only outlets, political newsletters, social media, magazines, news clip services. He records national news TV programs, watching them on Sunday to prepare for the week ahead.

“You’ve got to keep moving,” he says. “It takes me the whole day, even when I have nothing else scheduled, just to get through everything. But I’d rather have it that way. Who wants to be bored?”

Sabato clearly sees these mushrooming options for news about things important to democracy as a good thing. More voices, angles, coverage and scrutiny. Yet he also sees a downside.

“There is no common denominator. There’s nothing that all of us watch that’s serious. You know, people will watch ‘America’s Got Talent,’ which attracts millions of people, or one of these other shows that doesn’t have any real serious content to it. But we don’t start out from a common base of knowledge, and that has hurt us badly.”

Voting and Ethics

There is one basic action that would help quite a bit if more of us would take it, Sabato reminds.

“We the people need to always vote, and not just in November,” he says. “Participation in primaries and caucuses is critical, otherwise the ultra-partisans will pick the nominees from which we’ll have to choose. We also need to spend more time reading, thinking, and discussing elections and the issues before us. Common sense needs to guide us more than ideology in making progress. Something else is vital. We must think about the national interest – which may diverge from our personal interests. In government and politics, as elsewhere, the whole is greater than the sum of the parts.”

Sticking with the fundamentals, I am curious to get Sabato’s thoughts about a simplistic theory: If people would just practice basic decency and kindness with one another, then the political equivalent of road rage wouldn’t make it so impossible to have simple conversations and solve problems.

Sabato agrees to put on his analyst hat, commenting in a political context on several terms or values one might associate with kind or decent behavior.

The first is “ethics.”

“I think it’s in the ICU,” Sabato says. “But I don’t see how you can run a free society without a strong sense of ethics and ethical principles that govern and guide the individual and the polity.”

How about “courtesy?”

“What’s that?” he laughs. “Look, I’m on Twitter. I limit myself to 30 to 40 minutes a day, which isn’t easy. And I learn a lot on Twitter. I learn what people are thinking in the more extreme activist parts of society. Some people are very courteous on there, but most people are not. And that’s because of anonymity. That also relates to ethics. Is it ethical to strike out at people without identifying yourself so you have no responsibility for what you have said and done and the harm you’ve done on account of it?”

Then what about “consequences?”

“Every profession has different standards, but in politics, the standard has to be truth. There are edges of reality that can be debated as to what actually is true. But if you don’t believe that truth matters, you cannot have a democracy. It will not hold together.”

.jpg)