While Lincoln and his Unionist coalition stressed this redemptive approach to the conflict, their Confederate counterparts were proclaiming that Northerners and Southerners could never be countrymen again and that there had to be a separate Confederate nation.

“The premise of the Union War was that Southerners could be brought back into the national fold,” Varon said. “And as a result, Union rhetoric focused on the possible redemption of Southerners. Northerners very often resorted to metaphors to describe what they had in mind – Confederates were pupils who needed to be taught, patients who needed to be cured, children who needed to be parented, heathens who needed to be converted, drunkards who needed to sober up, madmen who should come to their senses, prodigal sons and errant brethren. All of this rankled Confederates.”

Because of the importance of restoring the South to the Union, Northerners would not recognize the depth of Confederate recalcitrance and resilience of Confederate nationalism.

“Northerners believed that their beloved ‘Union,’ which was their word for their representative government, should be bound together by bonds of affection, not coercion,” Varon said. “They believed that’s what the founders had intended.”

Thus to win the war, Northerners not only had to defeat the South on the battlefield, they had to restore those bonds of affection and persuade Southerners to love the Union again.

“This belief in Southern deliverance shows the power of human yearning. Part of the reason Northerners yearned for this is that they just had to believe that there was a way to end the war short of the total destruction of Southern society,” Varon said. “Northerners knew they couldn’t coerce the South into embracing the Northern point of view, and that they needed on some level to win some people back over.”

Varon explains that Northern leaders thought that being magnanimous after the war would change the hearts and minds of the Confederates. But, with a few exceptions, the defeated rebels remained committed to their ideals, leaders and cause even after the war, she said.

Lincoln viewed the emancipation of the enslaved as part of his strategy to save the South, believing that abolition would punish the elite slaveholders while benefiting the broad swath of white Southerners by removing the root source of contention in national politics.

“Supporters of emancipation argued that it would open the way for democracy in the South, for free speech and material and technological progress, urbanization and industrialization,” Varon said. “Emancipation itself is presented by Lincoln and his allies as redemptive, as part of this project of saving the South, and we can see Lincoln’s hopefulness right down to his last speech – ‘malice toward none, charity toward all.’ That is very much an expression of his abiding belief that the South could be reformed.”

Varon said she wants readers to understand the complexity of the issues involved in the Civil War and the strength of the prevailing ideologies.

“I think this book is about the fundamental idealism of the Union war effort,” Varon said. “It was a brutal war on both sides, and the North’s hard war tactics targeted and victimized civilians at times. But deliverance rhetoric was so strong that it was never displaced by hatred. There was always this core belief that Southerners could and should be brought back into the Union.”

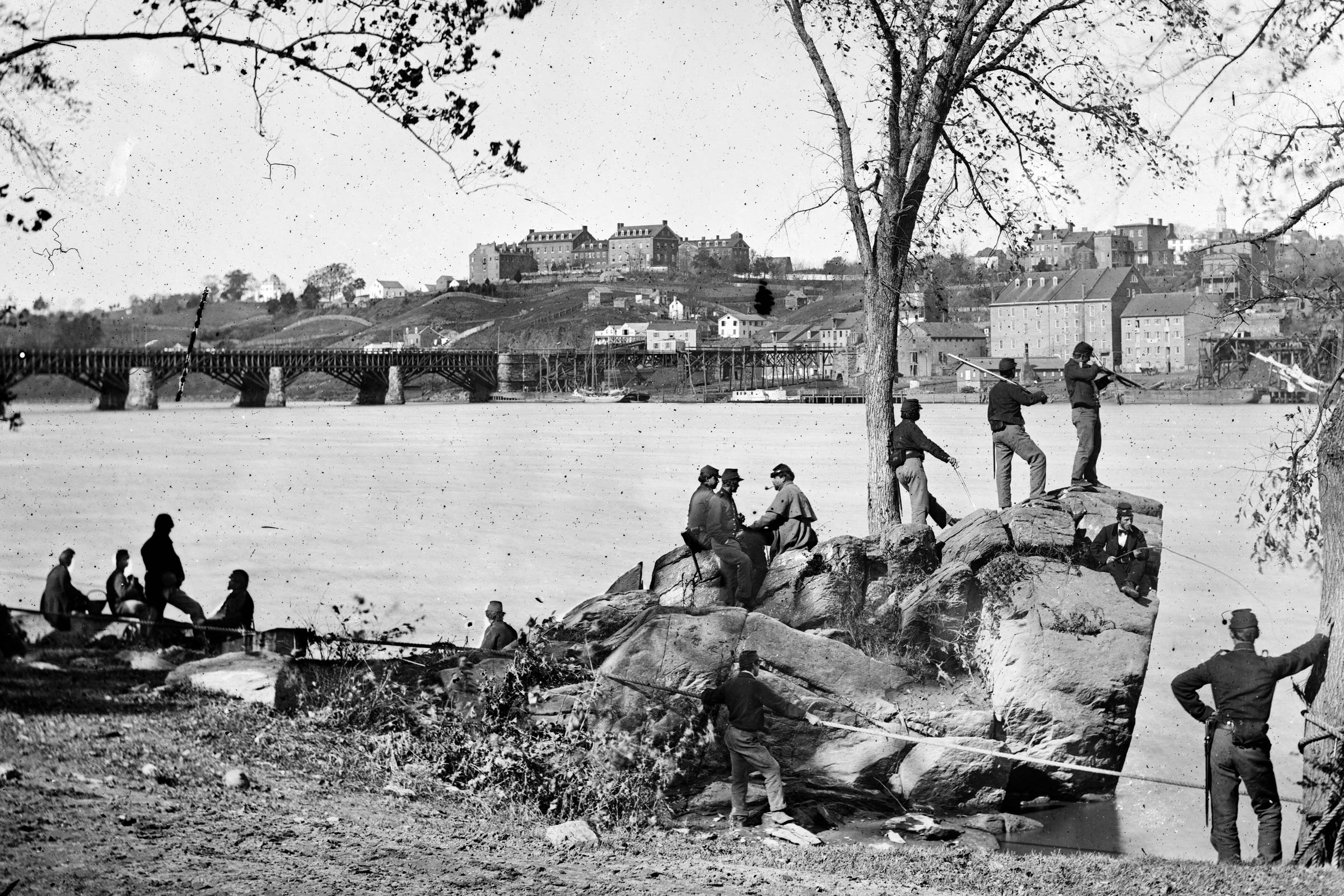

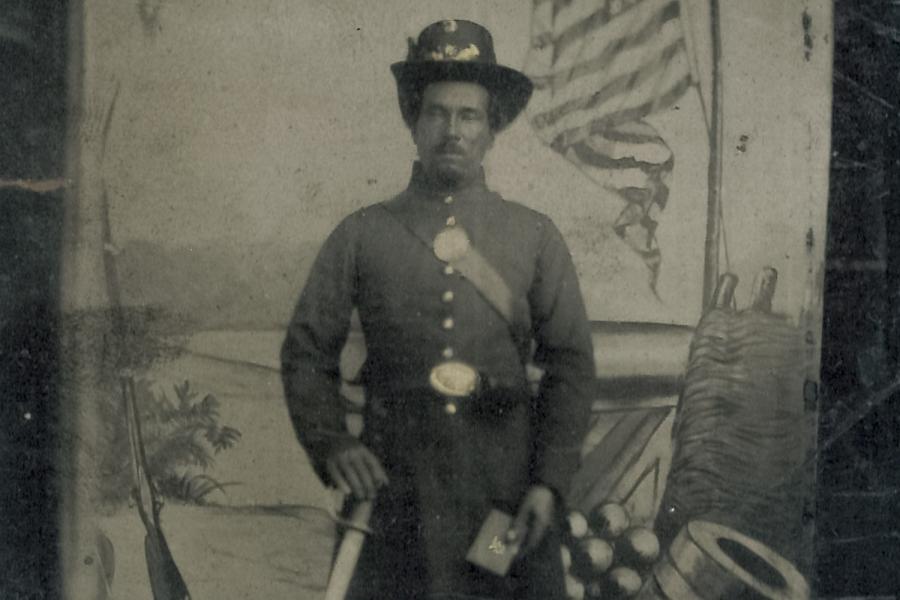

The troops trying to bring the South back into the fold came from a wide variety of backgrounds. Varon notes that 43% of Union soldiers were immigrants or sons of immigrants, many from Ireland and Germany. The Union forces also included about 200,000 black soldiers and sailors, about 80% of whom were from the South, as well as about 100,000 white Southerners from seceded states, which Varon said was further proof of Lincoln’s ability to form his coalition against the slave power conspiracy.

“As someone who had studied the South more than the North, I was surprised to learn about the diversity in the Union Army, from reading all those soldiers’ letters and diaries,” Varon said.

“There was diversity of political opinion. Northern soldiers represented a very broad political spectrum, from quite conservative Democrats in the opposition party to moderates like Lincoln to Radical Republicans and abolitionists, to all manner of views in between. There were fervent debates within the North and the Union Army over how to achieve Southern deliverance. Black soldiers and reformers, for example, emphasized that the nation needed deliverance from the sin of racism, and that true liberation would bring black citizenship and racial equality.”

To better understand these debates, Varon had to master the vocabulary of 19th-century politics and came to understand how people of that time revered the Union, fewer than 100 years old at the time.

“The Civil War is just endlessly complex and the only way to grapple with it is to go to the primary sources themselves and spend a whole lot of time with them,” Varon said. “I try to tune in those voices.

“The joy of this project for me is that I am constantly reminded that the Civil War has an endless capacity to surprise us. I have tried to integrate the story of emancipation and slave resistance into the story of the battlefield and electoral politics.”

In writing some sections of this volume, Varon stepped into the role of a military historian, something that was an exciting new prospect for her.

“I have learned how important it is for us scholars to get out of our comfort zone and take on new challenges,” she said. “I am not a military historian by training, but I wrote a lot about battles in this book and there is a learning curve in mastering that genre. While I did not start out as a military historian, I have become very much involved in what people today call a ‘war and society’ approach to military history, in which you relate military history to social history and social problems.”

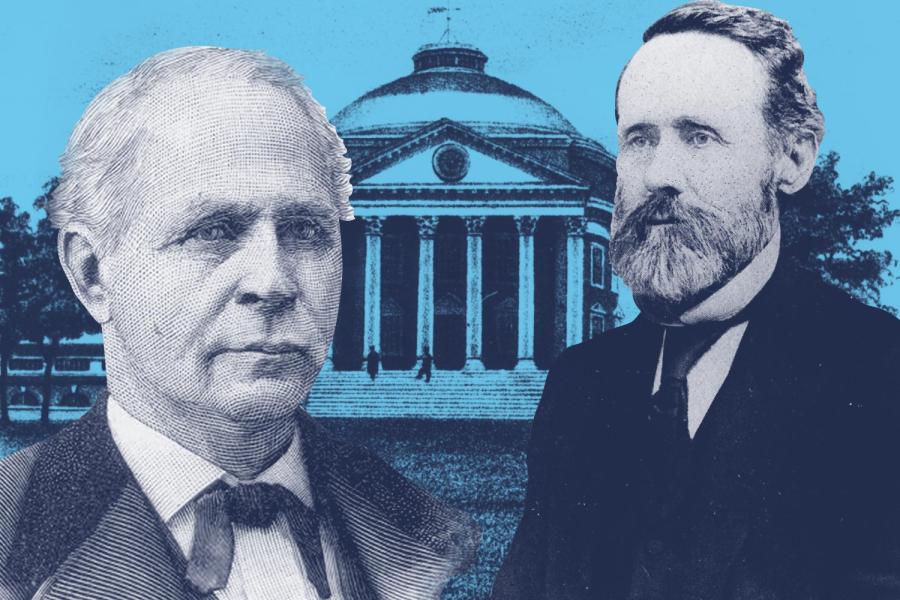

This semester Varon is reviving Gallagher’s popular course on American military history to 1900.

“The field of ‘war and society’ is an important strength of the Corcoran Department of History and I am glad to contribute to our many military history offerings,” Varon said.