April 9, 2007 -- In a world of virtual reality, online socialization and instant gratification, where does a child whose curiosity can only be satisfied by taking something apart and putting it back together again fit in?

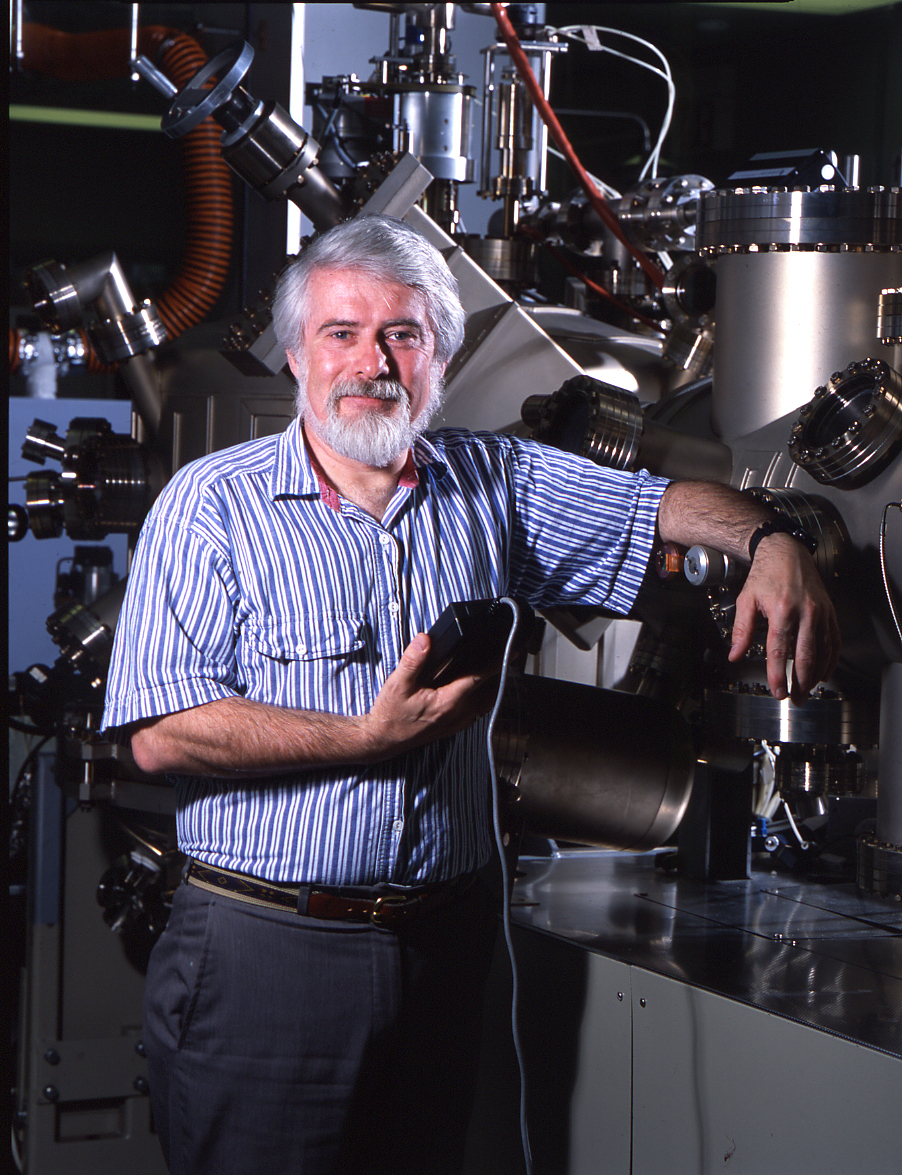

This question, and his lifelong commitment and dedication to education, prompted University of Virginia engineering professor John C. Bean to create a virtual alternative — the U.Va. Virtual Lab, a Web site five years in the making that employs emerging software visualization tools to explain technologies affecting our daily lives.

“I grew up in the ’60s, and back then, there were these companies that manufactured kits you could buy to walk you through the process of building a television or shortwave radio,” says Bean, the J.M. Money Professor in the Charles L. Brown Department of Electrical Engineering. “I worked on these kits with my father, because I was one of those kids who wanted to take something apart to learn how it worked. Today, children don’t have that option — you can’t take apart an iPod and figure out how it works.”

So began Bean’s journey. He met with two science instructors from local high schools and posed one important question: “Where can I be of most help to you in your science instruction?” Both teachers revealed that the problem was in the explanation behind “wow-factor” demonstrations. Students loved in-class demonstrations to illustrate concepts like basic charge attraction and repulsion for the entertainment value, but the instructors found that it was difficult to explain what was occurring behind the scenes to elicit the exciting visual part of the demonstration.

What if the “behind the scenes” causality could become part of the visual demonstration, Bean wondered. He took this idea to the National Science Foundation in the form of a proposal, which ultimately resulted in funding for the U.Va. Virtual Lab. With universities, community colleges and two high schools on board, the site began to take off.

Since his goal was to appeal to an audience much closer in age to the undergraduates he teaches than to himself, Bean began by recruiting engineering students to help with the projects. He set some basic parameters — the projects should involve microelectronics, Bean’s own field, or nanotechnology. “Beyond that, I wanted the students to choose something that would excite them,” said Bean. “Basically, the labs that we have created are what the students got interested in.”

Currently there are eight virtual labs on the site: Electronics, Microelectronics Teaching Lab, Microelectronics Production, Electricity and Magnetism Lab, Circuit Lab, Scientific Instruments, Semiconductor Science and Nanoscience. Each lab contains a variety of subject-relevant experiments from which a visitor can select. Once an experiment is selected, explanatory text, accompanied by animated images, guides the visitor through the experiment. In many cases, this visualization is also accompanied by a podcast narrated by Bean. The site’s content is written and recorded for high school students and college freshmen, although Bean has also received positive feedback from middle school students and teachers who are regular U.Va. Virtual Lab visitors.

Bean’s next challenge, spreading the word about the site, proved even more difficult than content creation. Even after most of the U.Va. Virtual Lab’s content was posted in 2005, search engine hits remained low, with the Web site’s pages generally listed no higher than the 10th page on a typical search for associated key words.

Through careful tracking of Virtual Lab site visitors, Bean learned that search engine rankings began to increase only after other sites began to link to the Virtual Lab. These links were the results of both solicited and spontaneous efforts: for example, in March 2005, 2,000 demonstration CDs were distributed at U.S. K-12 science education meetings. This strategy produced not only an immediate spike in site traffic but also steady growth in site use through the end of that year. One year later, in March 2006, a reader of the online magazine MAKE (www.makezine.com) posted a link to one of The Virtual Lab’s site pages to MAKE’s blog. This produced not only 10,000 hits in one weekend, but also an invitation from MAKE’s editor to regularly submit announcements of new Web pages.

These purposeful and unplanned exposures have made certain sections on the Virtual Lab’s Web site appear on the first and second pages of Google searches. As a result, the labs explaining how semiconductors and transistors work are currently the most popular sections of the site, accounting for 10 percent to 20 percent of the site’s overall traffic.

The statistics confirm the site’s growing popularity — but who is visiting the site? Bean conducted an analysis of visitors to The U.Va. Virtual Lab Web site over its first two years of fully public operation (2005-2006 and 2006-2007). His findings verify that the site is reaching those populations for which the content was intended. Through December 2006, the total number of Web pages and podcasts viewed was 616,988. Identified users included 329 U.S. universities and colleges (approximately 8.2 percent of the site’s traffic); 393 international universities and colleges (approximately 3.1 percent of the site’s traffic); 168 K-12 schools and organizations (approximately 1.2 percent of the site’s traffic); and 112 companies, including Internet service providers (approximately 87.5 percent or the balance of the site’s traffic). Visitors also include a veritable who’s who of international labs, including the Max Planck Institute; the Faunhofer Institute; France’s CNRS; Canada’s National Research Council; Belgium’s IMEC; and Sandia Labs, Oak Ridge Labs, Argonne Lab and Lawrence Berkeley Labs in the U.S. Indeed, The U.Va. Virtual Lab is being used by students and teachers alike in an instructive capacity.

Although the statistical data demonstate that the site is being used and can also illuminate who those users are, Bean does not get as much correspondence from teachers as he would like. But those direct interactions have been memorable. Not long after new labs were added on Atomic Force Microscopes and Scanning Tunneling Microscopes, both of which are on the leading edge of nanoscience, Bean received an e-mail from a colleague at the Science Museum of Virginia.

“I began answering the e-mail before I had read all the way through it,” says Bean. “I discovered that I was writing to a young man who was one of a group of students in the seventh grade. It was an example of how far down this could go. I wound up helping seventh graders understand something that usually only graduate students use.”

Bean expects the visitor count to the U.Va. Virtual Lab to surpass the 1 million mark this semester. “I’ve always been interested in innovative educational methods,” says Bean. “This generation does not have the same opportunity I had to physically dissect high-tech objects. So, through virtual reality, I hope to provide them with alternative tools for figuring out ‘how things work.’”

Bean is the 2003 recipient of the Charles L. Brown Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering’s Award for Teaching Innovation and of the 2004 University of Virginia All-University Teaching Award. He has published approximately 300 articles and texts and is the recipient of 14 U.S. patents.

To tour the Virtual Lab at U.Va. and for more information, please visit www.virlab.virginia.edu/VL/home.htm.

This question, and his lifelong commitment and dedication to education, prompted University of Virginia engineering professor John C. Bean to create a virtual alternative — the U.Va. Virtual Lab, a Web site five years in the making that employs emerging software visualization tools to explain technologies affecting our daily lives.

“I grew up in the ’60s, and back then, there were these companies that manufactured kits you could buy to walk you through the process of building a television or shortwave radio,” says Bean, the J.M. Money Professor in the Charles L. Brown Department of Electrical Engineering. “I worked on these kits with my father, because I was one of those kids who wanted to take something apart to learn how it worked. Today, children don’t have that option — you can’t take apart an iPod and figure out how it works.”

So began Bean’s journey. He met with two science instructors from local high schools and posed one important question: “Where can I be of most help to you in your science instruction?” Both teachers revealed that the problem was in the explanation behind “wow-factor” demonstrations. Students loved in-class demonstrations to illustrate concepts like basic charge attraction and repulsion for the entertainment value, but the instructors found that it was difficult to explain what was occurring behind the scenes to elicit the exciting visual part of the demonstration.

What if the “behind the scenes” causality could become part of the visual demonstration, Bean wondered. He took this idea to the National Science Foundation in the form of a proposal, which ultimately resulted in funding for the U.Va. Virtual Lab. With universities, community colleges and two high schools on board, the site began to take off.

Since his goal was to appeal to an audience much closer in age to the undergraduates he teaches than to himself, Bean began by recruiting engineering students to help with the projects. He set some basic parameters — the projects should involve microelectronics, Bean’s own field, or nanotechnology. “Beyond that, I wanted the students to choose something that would excite them,” said Bean. “Basically, the labs that we have created are what the students got interested in.”

Currently there are eight virtual labs on the site: Electronics, Microelectronics Teaching Lab, Microelectronics Production, Electricity and Magnetism Lab, Circuit Lab, Scientific Instruments, Semiconductor Science and Nanoscience. Each lab contains a variety of subject-relevant experiments from which a visitor can select. Once an experiment is selected, explanatory text, accompanied by animated images, guides the visitor through the experiment. In many cases, this visualization is also accompanied by a podcast narrated by Bean. The site’s content is written and recorded for high school students and college freshmen, although Bean has also received positive feedback from middle school students and teachers who are regular U.Va. Virtual Lab visitors.

Bean’s next challenge, spreading the word about the site, proved even more difficult than content creation. Even after most of the U.Va. Virtual Lab’s content was posted in 2005, search engine hits remained low, with the Web site’s pages generally listed no higher than the 10th page on a typical search for associated key words.

Through careful tracking of Virtual Lab site visitors, Bean learned that search engine rankings began to increase only after other sites began to link to the Virtual Lab. These links were the results of both solicited and spontaneous efforts: for example, in March 2005, 2,000 demonstration CDs were distributed at U.S. K-12 science education meetings. This strategy produced not only an immediate spike in site traffic but also steady growth in site use through the end of that year. One year later, in March 2006, a reader of the online magazine MAKE (www.makezine.com) posted a link to one of The Virtual Lab’s site pages to MAKE’s blog. This produced not only 10,000 hits in one weekend, but also an invitation from MAKE’s editor to regularly submit announcements of new Web pages.

These purposeful and unplanned exposures have made certain sections on the Virtual Lab’s Web site appear on the first and second pages of Google searches. As a result, the labs explaining how semiconductors and transistors work are currently the most popular sections of the site, accounting for 10 percent to 20 percent of the site’s overall traffic.

The statistics confirm the site’s growing popularity — but who is visiting the site? Bean conducted an analysis of visitors to The U.Va. Virtual Lab Web site over its first two years of fully public operation (2005-2006 and 2006-2007). His findings verify that the site is reaching those populations for which the content was intended. Through December 2006, the total number of Web pages and podcasts viewed was 616,988. Identified users included 329 U.S. universities and colleges (approximately 8.2 percent of the site’s traffic); 393 international universities and colleges (approximately 3.1 percent of the site’s traffic); 168 K-12 schools and organizations (approximately 1.2 percent of the site’s traffic); and 112 companies, including Internet service providers (approximately 87.5 percent or the balance of the site’s traffic). Visitors also include a veritable who’s who of international labs, including the Max Planck Institute; the Faunhofer Institute; France’s CNRS; Canada’s National Research Council; Belgium’s IMEC; and Sandia Labs, Oak Ridge Labs, Argonne Lab and Lawrence Berkeley Labs in the U.S. Indeed, The U.Va. Virtual Lab is being used by students and teachers alike in an instructive capacity.

Although the statistical data demonstate that the site is being used and can also illuminate who those users are, Bean does not get as much correspondence from teachers as he would like. But those direct interactions have been memorable. Not long after new labs were added on Atomic Force Microscopes and Scanning Tunneling Microscopes, both of which are on the leading edge of nanoscience, Bean received an e-mail from a colleague at the Science Museum of Virginia.

“I began answering the e-mail before I had read all the way through it,” says Bean. “I discovered that I was writing to a young man who was one of a group of students in the seventh grade. It was an example of how far down this could go. I wound up helping seventh graders understand something that usually only graduate students use.”

Bean expects the visitor count to the U.Va. Virtual Lab to surpass the 1 million mark this semester. “I’ve always been interested in innovative educational methods,” says Bean. “This generation does not have the same opportunity I had to physically dissect high-tech objects. So, through virtual reality, I hope to provide them with alternative tools for figuring out ‘how things work.’”

Bean is the 2003 recipient of the Charles L. Brown Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering’s Award for Teaching Innovation and of the 2004 University of Virginia All-University Teaching Award. He has published approximately 300 articles and texts and is the recipient of 14 U.S. patents.

To tour the Virtual Lab at U.Va. and for more information, please visit www.virlab.virginia.edu/VL/home.htm.

Media Contact

Article Information

April 9, 2007

/content/virtual-lab-actual-reality-uva