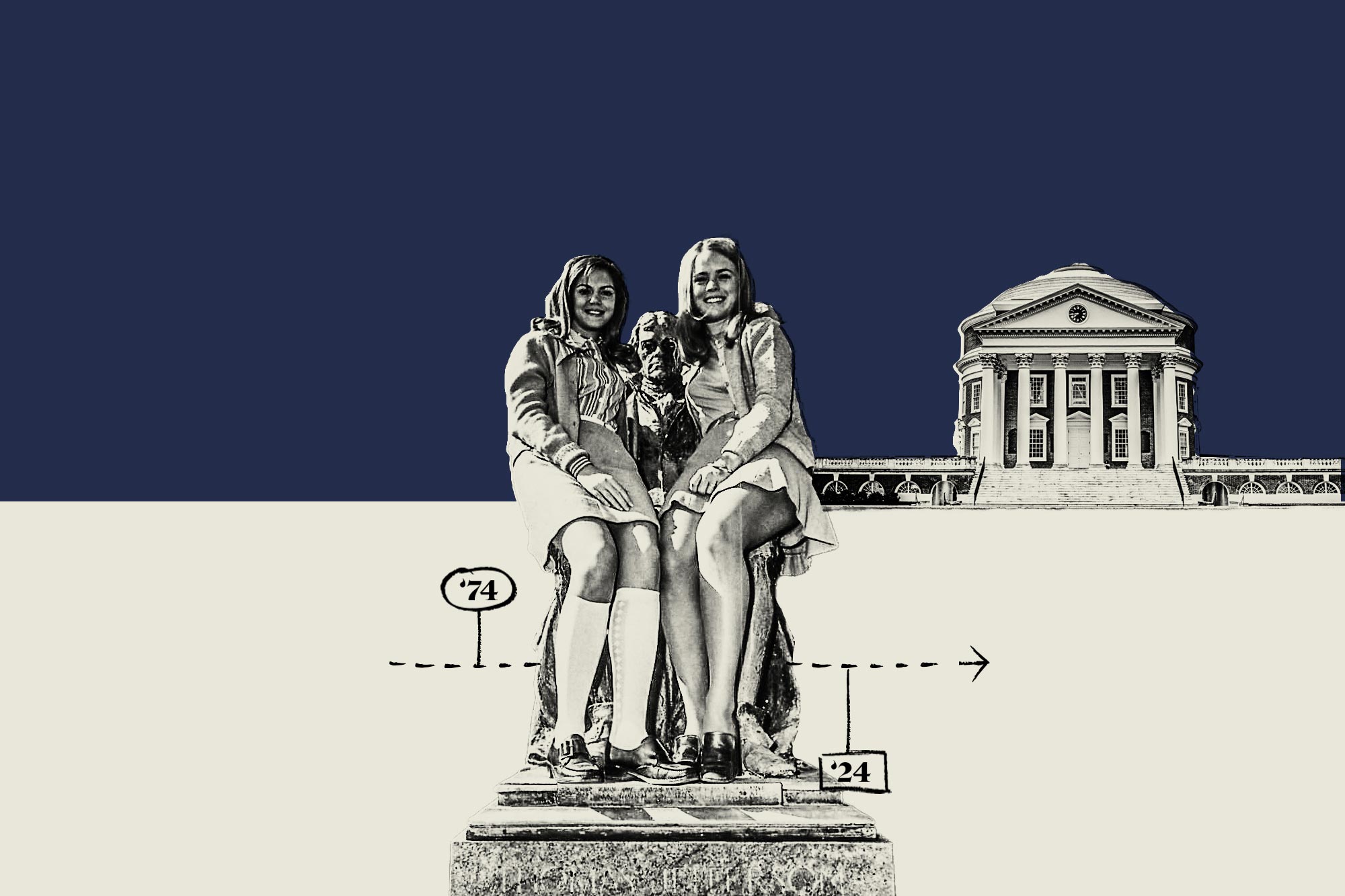

“There was certainly interest in the arrival of women but generally it seemed more inevitable than revolutionary,” she recalled. “That said, the atmosphere around the Observatory Hill dorms where all of the first-year women lived during orientation and the early weeks of the semester was a revelation to us. Large numbers of male students from the upper classes roamed the balconies of Webb, Tuttle, Watson and the other then-new dorms peering into the suites where we were meeting with our resident advisers.

“We immediately knew we were in for a wild ride.”

Student radios played a mix of anti-war protest songs, rock, funk and hints of the approaching disco era. “There was a lot of music going on that spoke to the times,” Shotton said. “Crosby, Stills and Nash, Marvin Gay, Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, The Who, The Grateful Dead, Led Zeppelin.”

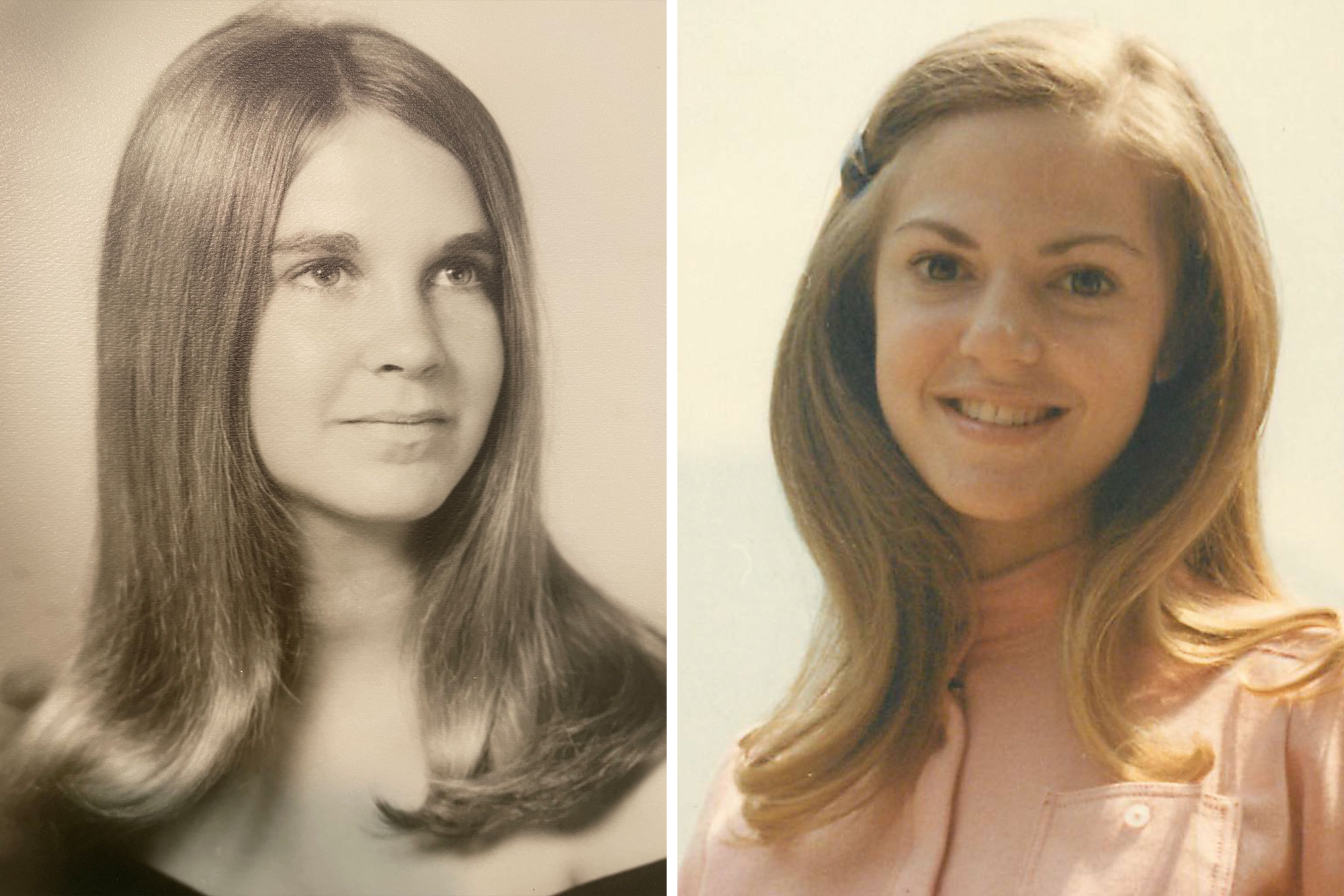

The breakup of the Beatles, the end of Simon and Garfunkel and Janis Joplin’s death all marked significant events in 1970. On Grounds, Shotton sensed most of her classmates and professors accepted the University was progressing, but it wasn’t universal.

“There were barriers. Mostly upperclassmen who wanted the school to stay all male, and some professors who shared the sentiment,” Shotton said. “I was usually one of a few women in a large class full of men. When I spoke up, I felt a lot of eyes on me and was very self-aware. It didn’t stop me. It actually taught me how to stand up for myself in uncomfortable situations.”

Many clubs were still male-only, and there were no women’s sports. Shotton, a high-school tennis player, founded a club tennis team for women. Other classmates created swimming and field hockey clubs. The yearbook, Corks & Curls, recruited women, and Shotton became an editor. Brown joined the Cavalier Daily, the student newspaper, and later was one of 14 classmates to earn the honor of living on the Lawn.