Best-selling feminist author Naomi Wolf created a firestorm in July when she published an open letter to millennial women. Ditch the vocal fry, she said, or risk not being taken seriously.

But what is “vocal fry”? This is how Wolf described it in an article in The Guardian: “That guttural growl at the back of the throat, as a Valley girl might sound if she had been shouting herself hoarse at a rave all night.”

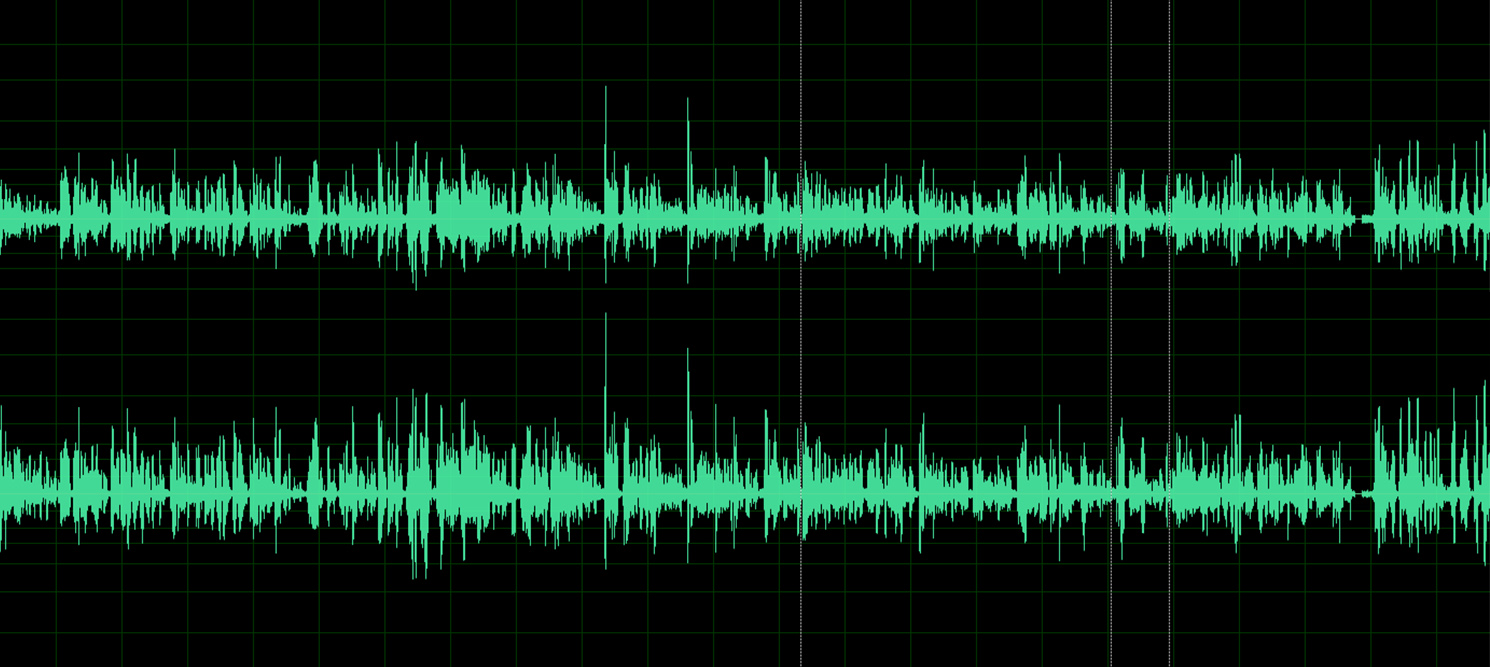

U.Va. drama Professor Kate Burke demonstrates the ‘vocal fry’:

Katy Perry, Britney Spears and yes, the Kardashians, all use this vocal tic, which is really ticking some people off. Bob Garfield, the host of Slate’s “Lexicon Valley” podcast, called the creaky voice “really annoying” and “repulsive.”

Wolf said the fry is doing young women a huge disservice. “What’s heartbreaking about the trend for destructive speech patterns is that yours is the most transformational generation – you’re disowning your power,” she wrote. “Young women, give up the vocal fry and reclaim your strong female voice.”

She cited a recent academic study that found female users are perceived as less competent, educated, trustworthy, attractive and hirable. The study also notes: “The negative perceptions of vocal fry are stronger for female voices relative to male voices.”

In fact, men use vocal fry, too. Famed American linguist Noam Chomsky’s voice is deeply creaky, and you can tune into an episode of NPR’s “This American Life” and hear host Ira Glass fry away. While women appear to employ the mannerism more than men, it is not gender-specific and commentators quickly seized on this to criticize Wolf’s plea.

U.Va. experts in the fields of otolaryngology, feminist studies and the spoken word all weighed in on this vocal affectation.

Otolaryngologist: Cleaning Up the Fry

Dr. Jim Daneiro, head of the Voice and Swallowing Clinic at U.Va, said he sees lots of cases of vocal fry in his practice.

“I started seeing it during my training at Vanderbilt in 2013. We would see younger women predominantly that would come in with vocal fatigue, where their voices would not last through the day.

“Glottal fry comes from using a lower subglottic pressure where there is not a lot of airflow through the voice box that creates creakiness,” he said. “It is a very inefficient way of producing sound.”

The affectation can damage vocal cords, though Daniero said it is not in itself the cause of traumatic damage.

“Those at higher risk of injury are people who are heavy voice users or talk loudly or aggressively,” he said. “Coaches, teachers and professors are at increased risk of getting a traumatic vocal lesion, polyps or a cyst.”

The specialist said patients can get better with voice therapy and it is rare that vocal fry results in surgery.

Gender Expert: Why Is This Even an Issue?

Claire Kaplan, director of U.Va.’s Gender Violence and Social Change Program, said the way women communicate is continually picked apart and she likened vocal fry to a type of dialect.

“Why are we analyzing how women speak and not men?” she asked. “I think it’s no more of an issue than if you have a very Southern dialect. I think we are overreacting to it. The people who are living with it in that age group don’t even hear it, so why are we having this conversation?”

She said the question that should be asked is why society values male voices over those of females.

Drama Coach: Speech Signals Identity

Kate Burke, an associate professor of voice and speech in U.Va.’s Drama Department, said vocal fry is incredibly difficult to hear and has no energy. It’s something young people employ with their peers, “but that doesn’t work with a prospective employer and it doesn’t work in a large space, so you are really limiting the scope of your communication and it makes for a small persona.”

Burke has given workshops and private coaching at theaters, conferences and medical schools, and to women’s group, news anchors and clergy.

She said when people speak, they use certain mannerisms that give listeners very clear cues. “In my ‘Voice for Theater’ course, I always begin with this question: ‘When people speak, what do we listen for?’”

Her students typically start with the most obvious dynamics: volume, pitch and rate. But as Burke probes further, the responses become more specific. “People start saying ‘agenda, education level, class, country of origin, aggressiveness.’ By the time we are finished, there are 25 things on the board and people say, ‘I’m never talking again!’”

The point Burke makes is that oral literacy is consequential and that speaking well, persuasively and in a committed way is important to succeed in the world.

The drama professor is quick to point out that vocal training is not robbing someone of their natural voice.

“What is habitual is not what is natural,” she said. “From the moment you are born, you have been subjected to so many conditioning forces and your voice is formed by that.”

No gender owns any particular pitch range, and women are no more prisoners of speaking in the high range than men in the low, Burke said. “What the voice should be doing is going from way high for emphasis and going all the way down, and that is gorgeous to the ear – it’s like a song.”

Hear Burke read from the Declaration of Independence to demonstrate other vocal affectations:

Media Contact

Article Information

August 12, 2015

/content/whats-voice-debate-over-vocal-fry-and-what-it-means-women