“Congressman Miller and his district staff were scrambling to create the appearance of local support for what was initially a Washington-driven park proposal,” Warburg wrote in his book.

Miller won Kennedy’s support for the plan, but little more than a year after the bill’s signing, both Kennedy and Miller were dead – Miller in a plane crash in October 1962, and Kennedy from an assassin’s bullet in November 1963. As the federal government moved on to more pressing issues, the Point Reyes Seashore project slowly foundered, with little support and little money to buy the land.

By 1969, the National Park Service proposed to sell some of the land it had already acquired, subdivide a section of the peninsula, and build 4,500 houses.

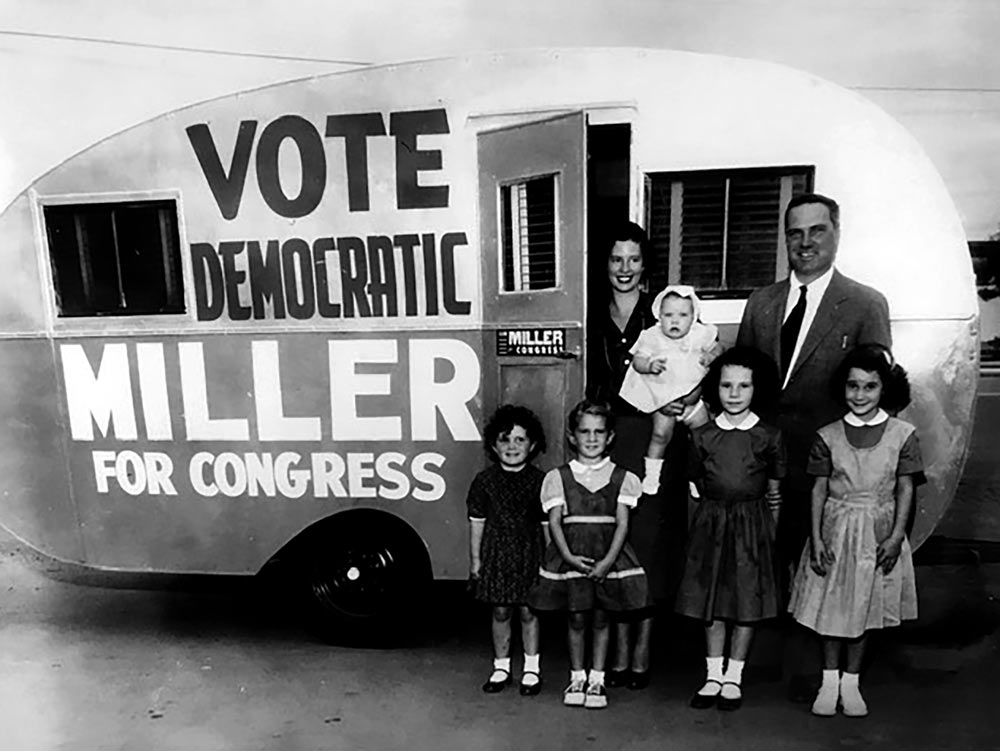

That spurred Katherine Miller Johnson, widow of Clem Miller, into action. When she married Clem Miller, she was a 19-year-old Bryn Mawr College student, who left college. When he died, she was a young widow with five daughters. Six years later, when she had heard of the Park Service proposal, she was remarried, had another child and was helping raise three stepchildren.

But she knew what Point Reyes meant to Miller.

“One by one by one by one, she was writing to key influential journalists and politicians around the country about this park,” Warburg said. “She was writing The New York Times and The Washington Post, creating stories, getting free media, writing [former First Lady] Lady Bird Johnson to ask her to write President Richard Nixon, writing [Nixon’s domestic policy adviser] John Ehrlichman. She flew back to California and paid for the Save Our Seashore campaign with personal funds.”

Neither was Katherine Johnson afraid to play the widow card. She readily conceded that she leveraged it for access to influential people and used their sympathy to negotiate with committee chairs before whom she testified.

While Katherine Johnson was the public face of the campaign in congressional testimony, Nixon, a California native, was looking at the midterm elections and calculating that support for preserving Point Reyes would be rewarded at the polls. In the end, Nixon signed a bill increasing the funding for the Point Reyes National Seashore from $14 million to $54 million. As part of this Point Reyes deal, more than $300 million for other parks projects around the country was also released by the Nixon administration.

Nixon was also influenced by Ehrlichman, another surprise for Warburg.

“I didn’t realize the depth of the White House support for Point Reyes,” Warburg said. “I grew up thinking John Ehrlichman was a villain from Watergate days. I didn’t realize he was actually one of the heroes of Point Reyes. His best friend from their time together at Stanford Law School was [U.S. Rep.] Pete McCloskey, who helped him raise his kids – and he was fighting for the park. There are a lot of surprises in this story, including the fact that Republicans like Nixon and Ehrlichman played a key role.”

Point Reyes, Warburg realized, was not a regional story. It was a turning point in the nascent national environmental movement, with people such as Katherine Miller Johnson and Ehrlichman as the fulcrums on which its history pivoted.

“The whole environmental consciousness of 1969 and 1970 and just an extraordinary amount of legislation all happened right around this time,” he said. “The National Environmental Policy Act, the Endangered Species Act, the renewal of the Land and Water Conservation Fund, the Marine Mammal Protection Act , the creation of another dozen national seashores and lakeshores– these all happened right after this fight.”

Researching the book was also a personal journey for Warburg, whose father, Felix, had been head of the Marin County Planning Commission and a player in the Point Reyes saga. Although he was unaware of his father’s role at the time, Warburg discussed it with him before he died and found that newcomers to the area, such as his parents, were often the people who most wanted to preserve the peninsula against the threat of subdivision.

“The newcomers recognized how precious it was,” he said.

While Warburg had never heard of Katherine Miller Johnson, who died in 1991, in connection with Point Reyes, he knew his parents were friends with Clem Miller and his wife. During his research, Miller’s daughters provided him photos of their parents together.

“There were 24 rolls and contact sheets from his last 1962 campaign, and one of the last rolls was shot in our living room,” Warburg said. “And it was my mom and dad sitting talking to Clem Miller, about stuff they cared about. That was the proof. I’d known all along that they were close, and that they cared, and that they would be talking about these environmental issues.”

Despite the diverse cast of characters, Warburg believes the thriving park would not exist today were it not for Katherine Miller Johnson, a woman so erased from the story that there is nothing about her in the signage at Point Reyes.

“This was an example of a woman nearly forgotten in the first drafts of history,” Warburg said. “I thought as we examined this case study to help guide current policymaking challenges, it was important to rectify that omission.”